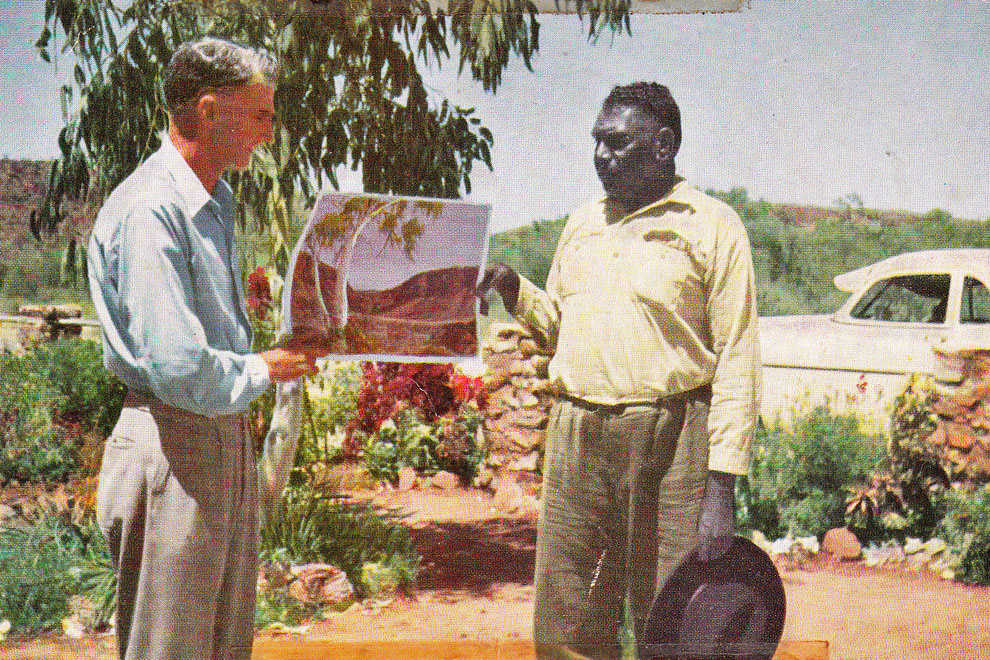

Battarbee and Namatjira

By Martin Edmond | Giramondo Press | $29.95

During the 1930s new railways and the promise of mineral wealth fuelled a surge of interest in the Australian interior. Fascinated by the potential of those vast open spaces, geologists, prospectors, journalists, artists and others travelled inland, and among them was Rex Battarbee, a returned soldier who’d lost the use of his left hand in a wartime accident. Rather than becoming a lift attendant or a taxi driver – the employment options more usually suggested for disabled ex-servicemen – Battarbee had chosen to train as an artist. A country boy from Warrnambool, he began painting watercolour landscapes to escape being cooped up in the city as a commercial artist.

In the mid 1930s, Pastor Friedrich Albrecht at Hermannsburg mission introduced Battarbee to Albert Namatjira, whom he invited on a painting expedition to Palm Valley. Namatjira had already revealed his talent by burning designs on artefacts and producing several watercolours, including an imitation of a Battarbee landscape hanging in Albrecht’s office. During their trip, the first in a series of collaborative artistic ventures, Battarbee taught Namatjira watercolour techniques. Theirs was far from a conventional master–pupil relationship, for Namatjira “reciprocated with a knowledge of country that ran the gamut from simple foods to complex story-telling.”

Namatjira was a quick, even virtuosic, student. His first one-man show, in Melbourne in 1938, sold out in three days; reproductions of his watercolour landscapes, which became synonymous with the Australian interior, would eventually hang in households across the nation. Although Battarbee was also reasonably successful by the standards of the thirties, his life, work and art are now less remembered outside central Australia.

Martin Edmond’s dual biography, Battarbee and Namatjira, re-centres Battarbee’s story and contribution in the better-known narrative of Namatjira and the emergence of Aboriginal art movements in central Australia. He shows how Battarbee was particularly influential in the development of the Hermannsburg Art School, teaching young Aboriginal men painterly techniques, acting as an agent and dealer for the Namatjira Arts Committee and staying on to keep the Hermannsburg mission open after the Lutheran missionaries were accused of having Nazi affiliations. Later, he proposed an Aranda Arts Council, which he chaired himself, after it was set up in Alice Springs, to make sure it didn’t fall under the control of the mission or the Native Affairs department.

Edmond revisits the question of whether Namatjira’s renown was built on the novelty of an Aboriginal man painting successfully within Western traditions and forms during a period marked by a “vogue for the primitive.” To use John Reed’s words, was his art “only the clever aping of an alien art form”? Battarbee, who worried that his influence meant that Namatjira’s work and techniques too closely mimicked his own, went on to encourage other Aboriginal artists to develop their own style.

Using previously unpublished material from Battarbee’s diaries, Edmond explores what each man brought to their artistic partnership (although he doesn’t elaborate on the skills and techniques Namatjira may have brought from his own culture). Battarbee said that he taught Namatjira how to “analyse the landscape” and to “see colour in a way that was sound and true,” in the process enhancing his own artistic rationale and technique: “I felt the need to work out a new way and to achieve luminosity.” Central to his approach was the use of techniques developed by John Ruskin and other nineteenth-century watercolourists, including the layering of pigment to intensify colour and bring out “the essence beyond appearances.”

Although Namatjira learned “to see differently,” Edmond suggests that this way of looking did not replace “but augmented” how he already saw. As a result, Namatjira’s work expressed Arrernte perceptions of landscape and cosmology through the medium of watercolour. “Namatjira painting,” Edmond writes, “can be representational of a landscape, an actual simulacrum of it and also embody equivocal presences that resemble – and perhaps are – totemic beings who are neither representation nor simulacra but partake of the essence.”

Battarbee and Namatjira’s other achievement is to portray an unconventional cross-cultural friendship. It takes up the challenge of negotiating how two lives intersect without the formal constraints of marriage, for example, and managing the weight and influence of each subject’s trajectory on the other.

For much of the book, Battarbee is an unobtrusive, self-effacing figure, the leading support actor to Namatjira’s tragic protagonist. Both were quiet, reticent men: Edmond describes Battarbee as “an even-tempered, even-handed man,” while Namatjira was “a highly emotional and extremely sensitive man who must, because of his circumstances, keep what he feels hidden most of the time.” The book’s early chapters face the particular difficulty of trying to relate two quite different lives in separate reaches of the continent, which perhaps makes the friendship all the more interesting and unusual. Edmond suggests that the “lockstep” arose from the fact that both had spent a period in exile from their society: Battarbee during his wartime experience and years in hospital, and Namatjira after marrying a bride “wrong way,” both culturally and as far as the missionaries were concerned, and then leaving Hermannsburg for some years.

For me, the narrative gains traction with the men’s initial meeting and the development of their partnership, after which events in Namatjira’s life take on the painful momentum of tragedy. Edmond’s depiction of their friendship has resonances with anthropologist Peter Sutton’s notion, in his book The Politics of Suffering (2009), of “unusual couples” or negotiated relationships that are marked less by the pairing of “representatives of coloniser and colonised, male and female, or black and white” than by “individuals whose experiences of each other were unusually complex, may have been at times unusually intense, and often had an impact on both individuals over a long period.”

As anthropologist John von Sturmer writes, “What is crucial to these relationships is that they create their own order – in which blackness/[versus] whiteness and the rest of that categorical baggage simply go out the window.” Sutton lists various “frontier pairings” between Aboriginal individuals and missionaries, anthropologists, nurses and others who have contributed to “the creation of knowledge and understanding” that transcends the cultural divide in ways more balanced than the dynamic between the individual and the corporate in contemporary Australian Indigenous affairs.

For Battarbee and Namatjira, it is the exchange of artistic and cultural knowledge and the pursuit of luminosity that takes their alliance beyond this divide. Each man, writes Edmond, is “less a wanderer between worlds than a progressive sojourner in a sophisticated, manifold reality.” In Battarbee’s case, it’s his autonomy as a largely self-supporting artist – not subject to structures such as the mission and native affairs – that enables him to develop not only an artistic partnership but also a lifelong friendship with Namatjira. His story contrasts with the more controlling interest of others who are embedded in conventional structures of the time, including Pastor Albrecht at the Hermannsburg mission and John Brackenreg, Namatjira’s agent in later life.

A career as an artist also provided a satisfying psychological and spiritual fit for Namatjira, allowing him to experience some independence as well as maintain connection with country. But he was unable to exercise his autonomy as an artist and capitalise on his career’s success to the fullest. One of the book’s refrains is Namatjira’s request that he be left alone to paint in the way he wanted – free from the supervision and demands of missionaries, art dealers and others – and to spend his money how he chose. In one poignant example, Edmond describes how Namatjira was able to purchase land in Alice Springs on the proceeds of art sales but unable to build a house to live on it because the provisions then in force did not permit him as a full-descent Aboriginal man to stay in town after dark.

Namatjira was understandably disgruntled at having to pay income tax while living in poor conditions in a camp on the edge of town, the circumstances of which later brought him into contact with the law and custody after he supplied alcohol to relatives. An increasingly embattled figure, Namatjira’s story is that of the Aboriginal man who achieves some success in joining “mainstream” society but is ultimately ruined by its punitive and contradictory structures.

Battarbee and Namatjira interweaves the narratives of this unusual couple against the backdrop of a series of seismic shifts in post-settlement central Australia. Beginning with a wide-angle focus on essence (tjurunga) in Arrernte cosmology, it recounts the arrival of the explorers, Lutheran missionaries and anthropologists, as well as the impact of two world wars (in stimulating an interest in Aboriginal art and souvenirs, for example) and of policy regimes such as assimilation and the extension of citizenship rights to Aboriginal people. Edmond also provides a fascinating account of the development of the Aboriginal art sector in central Australia, including the management of artists’ sales, issues concerning provenance, authenticity and the early use of an Aboriginal trademark, and the influence of Namatjira, Battarbee and the Hermannsburg school.

Battarbee and Namatjira counterpoints personal narratives, histories and paradigms of thought and policy dexterously. It presents a richly detailed, carefully realised and absorbing portrait of an unconventional alliance across a cultural divide, and it reads as smoothly and compellingly as a novel (with the italicisation of quoted material aiding the flow of the prose more than standard forms of academic citation). In revisiting Battarbee’s contribution to Namatjira’s development as an artist, it’s a testimony not only to the value of friendship but also to a quiet and unassuming life well-lived.

Battarbee and Namatjira is a nuanced and sophisticated portrayal of the complexities and ambiguities of mid-twentieth-century Aboriginal–settler relations, and a captivating read for anyone interested in the history of central Australia and its Aboriginal arts movements. •