In the mid 1970s, as part of my research for a Master of Arts thesis on the prime ministership of Harold Holt, I had the opportunity to interview twenty-one people (mostly current and former MPs) who I hoped would offer illuminating observations about my topic. The most significant were Paul Hasluck, John Gorton and William McMahon: respectively a recently retired governor-general (and former senior cabinet minister) and two former prime ministers. Hasluck was a knight by the time of the interview; Gorton and McMahon would secure their gongs in subsequent years.

Forty-five years later, it seems worthwhile to reflect on those three interviews in particular, aided by notes I took at the time and later revelations about some of the contentious matters I raised with the three men.

At the time of our conversation, it had been six months since Hasluck had completed his term as governor-general; his public life was effectively over. Gorton and McMahon were still MPs, by contrast, having remained in parliament after losing office; each was seeking (with minimal success) to retain some influence in Liberal Party and national affairs. All other things being equal, one might have expected Hasluck, the private citizen, to have fewer inhibitions.

Of course, all other things are rarely equal, and any hope of startling revelations from Hasluck was tempered by an understanding that he was an old-school conservative, with a media image as colourless and bland, committed to principles of discretion and restraint, and unlikely to have undergone a personality change after leaving office. During his parliamentary career he had been renowned for his disdain for the plotting, scheming and deal-making of his trade: indeed that “failing” was said to have contributed to his loss to Gorton in the Liberal leadership contest after Holt’s death in December 1967.

It had not been my plan to fill the thesis with quotes from MPs, but where I did wish to cite an interviewee’s comment I undertook to provide him with the context of the quote and seek his written approval. (Yes, they were all men.) Hasluck, however, pre-empted this plan when he wrote agreeing to meet me, making clear that he was “willing to have a conversation… but not willing to have any of our conversation recorded or to be quoted as a source of information.”

In fact, he went further, expressing his lack of sympathy for any excessive dependence on interview-based research. He was “appalled by the quick books on current affairs by journalists,” he wrote, “where backroom gossip and speculation becomes accepted and quoted in academic studies as being ‘history.’” Given that Hasluck had been (among other things) a journalist and a historian before entering parliament, this was heavy stuff. He was to be my first interview and it was dawning on me that I might have been better served starting off with a lowly backbencher.

My apprehension proved misplaced when we met in Perth in January 1975. In person, Hasluck was immensely courteous, not remotely combative, engaging, informative and expansive. It was an early lesson for me about the limited value of media images. In two separate parts of the interview, he was critical of Holt’s dependence on “public relations men” and associated “gimmicks” — an obvious reference to Holt’s press secretary Tony Eggleton — viewing this as the start of the (regrettable) Americanisation of Australian politics.

Hasluck had been external affairs minister under Holt, and during the interview he referred to what he clearly saw as his leader’s excessive faith in personal contacts and tendency to exaggerate the advantages of being on first name terms with heads of government. As Hasluck saw it, the department did the “real” work of foreign policy.

He believed that Holt was secure in the party leadership and would have survived any challenge, although critics might have discounted this confidence in the light of Hasluck’s relative detachment from internal party intrigues.

More surprising for me was his reference to the problems treasurer William McMahon was creating for Holt by “spreading rumours and lies.” Obviously, Hasluck had never gone on the public record with such criticism of McMahon, and telling me didn’t change that. Nor would he have conveyed such a view to any members of that species he despised — the press.

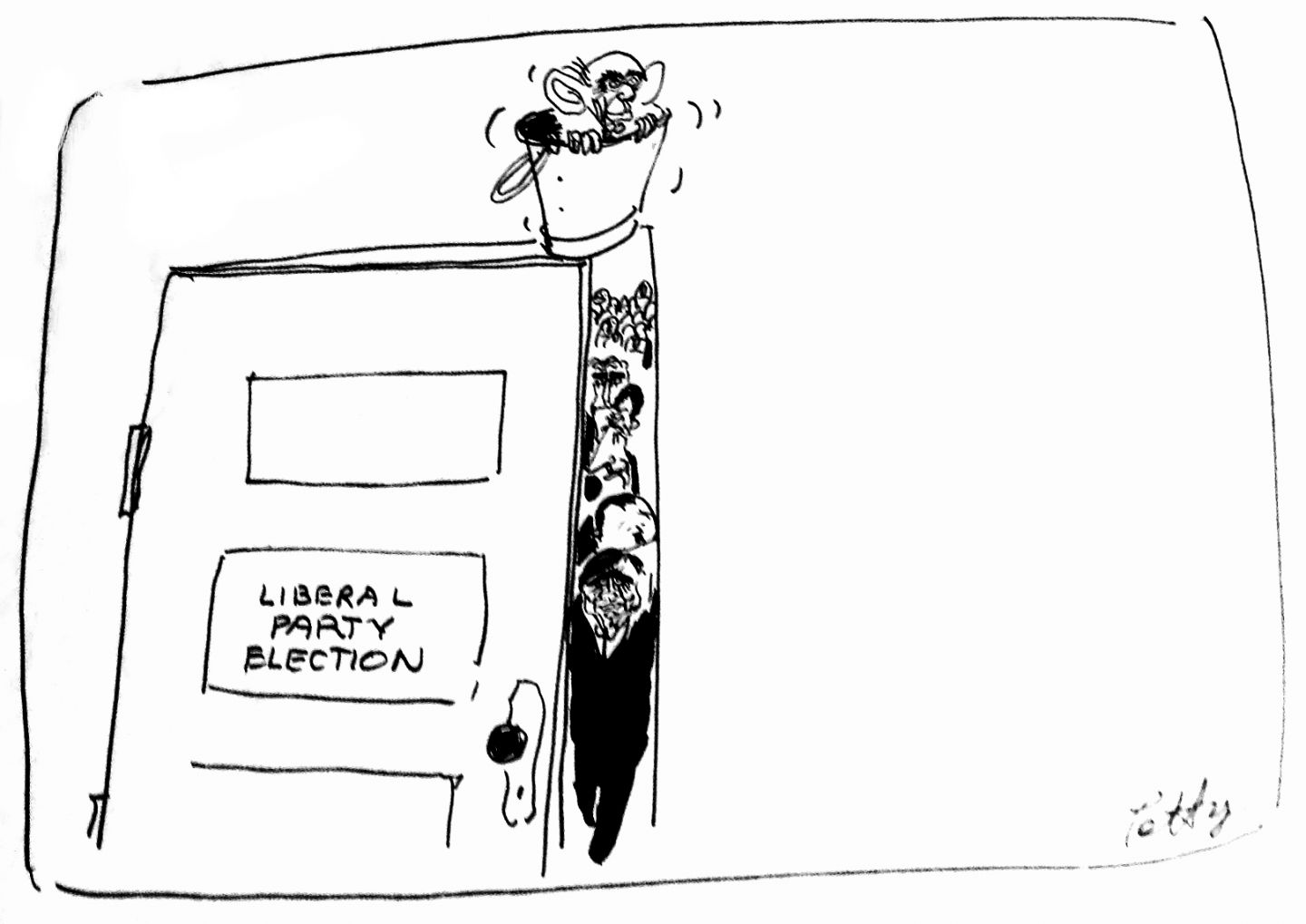

“Party trick”: cartoonist Bruce Petty’s depiction of William McMahon’s destructive capacity.

In later years, however, the public could access his anti-McMahon views in considerable detail, notably in The Chance of Politics, a collection of pen portraits of political personalities he had observed during his time in Canberra, which was published by his son Nicholas after his death. Among the words he used to describe McMahon — a “contemptible creature” — were disloyal, devious, dishonest, untrustworthy, petty and cowardly. Similar scathing observations about his former colleague can be found in Hasluck’s notes from his term as governor-general, held in the Australian National Archives.

The contrast with that rugged, idiosyncratic individualist John Gorton could hardly have been greater. In Gorton’s first interview with me, in Canberra in May 1975, the then Liberal backbencher was critical of Holt for his handing of the Voyager affair and the VIP aircraft affair — two scandals that had caused the government much embarrassment — and especially for his failure to discipline party rebels who made trouble over the Voyager. Not surprisingly, he denied any involvement in discussions to replace Holt as PM, but the denial is credible. Without the lower house vacancy ultimately created by Holt’s death, there was no obvious transition route for a Senate leader to change houses in order to become PM.

Gorton did advise me that Liberal Party whip Dudley Irwin had consulted him over the letter, sent to Holt just before his death, that sought a discussion about concerns that the government had not been performing very well for some time. It would not seem unusual for Gorton, as government Senate leader, to have been consulted. While contending that any challenge to Holt would have been unsuccessful, he could not resist the temptation to suggest that McMahon may have been involved in efforts to undermine his leader.

An opportunity arose in October 1976 for a further discussion with Gorton, now a private citizen following his unsuccessful attempt to win an ACT Senate seat at the 1975 federal election. He took up a very brief appointment as a visiting fellow in the Department of Government at the University of Queensland, where I was then located. In a short second interview, two points stood out.

First, Gorton recalled the story of how former prime minister Robert Menzies summoned McMahon after the leaking of cabinet documents, forced him to sign a confession and threatened him with dismissal if he committed further offences. I am unsure as to how widely known this story was at the time of Gorton’s telling, but it has featured in later accounts of the era, including in Patrick Mullins’s biography of McMahon.

Apparently, Holt didn’t “inherit” the commitment. Gorton claimed that McMahon resumed his leaking habits, which mostly related to an ongoing policy (and personality) war with Country Party leader and deputy PM John McEwen. McEwen attacked McMahon at several cabinet meetings, reflecting the toxic relationship that would see McEwen veto McMahon from succeeding Holt.

On Australia’s participation in the Vietnam War, Gorton claimed that the cabinet consensus lasted until Holt’s final decision (in late 1967) to send more troops. At that meeting, Gorton voiced lone dissent, feeling that Australia had “done enough” and that the United States was “half-hearted” in its war effort. Not quite hawk turning dove, it was nevertheless indicative of the approach Gorton would take as PM: the Australian commitment was not increased on his watch.

Interesting as this conversation was, much more colour attended the lunch held in Gorton’s honour during his visit to our department. There was plenty to eat and drink, and the former PM held little back as he offered (inter alia) a keen analysis of McMahon’s personality failings. It might be observed that some of the language used was not quite consistent with scholarly norms.

Knowing that I would be in Canberra a few weeks later, Gorton generously invited me for drinks with himself and his wife Bettina at his Red Hill home. The visit called for best behaviour and I made no attempt to outdrink Australia’s nineteenth prime minister.

A major purpose of that Canberra visit was an interview with McMahon, a backbencher since his election loss in 1972, with nearly another decade to serve in that role. At the time we met, progress figures from the 1976 US presidential election (in which Jimmy Carter defeated Gerald Ford) were coming through and McMahon was following the result on a small transistor radio. Turning his attention in my direction, he made a point common to several interviewees — that Holt was more concerned with the politics of policy-making than Menzies had been. He also noted that there were more aggressive exchanges at Holt’s cabinet meetings than had been the case under Menzies. Specifically, his nemesis McEwen “went to more extreme ends.” This was probably a reference to the Country Party leader’s criticism of McMahon’s leaking. McMahon told me that he regarded McEwen “as a psychiatric case.” Now, that would have been worth leaking — by me!

On Holt’s leadership, McMahon claimed that there had been discussions, but that he was oblivious to them because his role as treasurer was “very demanding.” It was not for me then, or now, to characterise this as a blatant lie, but I suspect that any Canberra journalist sitting in on our chat might have burst out laughing. McMahon did make the point that Gorton’s supporters seemed suspiciously well-prepared when Holt suddenly died.

It was obviously a rewarding experience to be able to interview a range of political figures, even if most of what I gathered provided background and context rather than revelations to be quoted in my thesis, and the relevant cabinet papers were decades away. The three men had been major players during that fascinating time when the predictability of the Menzies era gave way to a period of sustained instability within the Liberal Party. •