Luke Dodd and Michael Whyte’s documentary Looking for Light gives us a series of glimpses of the extraordinary career of one of the twentieth century’s most outstanding photographers, one who had a particular gift for photographic portraiture. Jane Bown’s career began in 1949 when, as a young and recently qualified photographer, she landed a job with the Observer in London. She was to remain with that newspaper for more than five decades, photographing people – most of them famous but some of them not – to accompany profiles, interviews and the news items of the day.

Now in her late eighties and with her memory fading, Bown nevertheless retains her eye for the telling detail. Early on in Looking for Light she recalls a visit she made to Paris with a friend when they were both in their mid-twenties. Her friend “wore a green hat,” Bown remembers, “and I wore a red hat.” Later in the film she recalls, with a mixture of stoicism and regret, her youthful presence at her mother’s funeral. Again she retains in her mind the telling detail, and again it is a hat. “I was wearing,” she says, appearing to conjure up the scene in her mind, “a little black beret.”

Hats and hair have always fascinated Bown. “She loved the tops of people’s heads,” says the photography scholar Patricia Holland in one of a number of illuminating comments she makes in the film. Hair, in Bown’s images, whether luxuriant or sparse or somewhere in between, frames and crowns and defines the face underneath, appearing in some cases almost to have a life of its own. Individual strands are discernible, the light bouncing off them to convey texture and substance. For many years Bown used the same Rolleiflex camera, long after that particular model was superseded, for “its remarkable capacity to capture every little detail and texture,” including the detail and the texture of hair. (In 1964 she changed to an Olympus SLR – “I take two cameras and indoors I generally have them set at 1/60th at f/2.8,” she said in 2000, in one of her typically spare comments on the technical details of what she did for a living. She hit it off with Elia Kazan because he knew immediately, by watching the way she prowled the room looking for light, what settings she would use.)

Occasionally, the sitter in a Bown photograph appears wearing headgear of some sort. It may be a fanciful observation, but it often seems that the hatted among Bown’s many subjects – as distinct from the hatless majority – are the truly super-sized personalities, the self-created and the very much larger-than-life, the ones who required something extra to hold them within the frame. Among these are the images of Boy George (1995) in an outsize black hat, decorated with bejewelled horns, or Eartha Kitt in a headband (1970), with her trademark stern yet sultry expression, or Cecil Beaton looking arch and manipulative in an astrakhan (1950), some of them viewable in full-screen mode at the Guardian webpage dedicated to “Jane Bown: A Life in Photography.” Hats can be seen as a component of the personality of the sitter, and Bown clearly saw them that way, but when it comes to what might be called external accessories – chairs, for example, or mirrors – she only rarely introduces them into the frame. She does quite often make use of the subject’s hands, however, in rather the way that she uses hats to position or help to define the head, as in her famous portrait of Björk.

Jane Bown’s portrait of the singer Björk. Hot Property Films

The portrait, which is lingered over in the film and also appears on the cover of Bown’s book Faces: The Creative Process Behind Great Portraits (2000), shows the singer’s head in extreme close-up, with only her eyes, and of course her hair, visible. The remainder of her face is covered by her hands, the freckles on her nose visible between splayed fingers. In Faces, Bown provides a brief paragraph of commentary on this photograph, as she does on each of the 300 or so portraits included in the book; often these comments are rather flat and suspiciously academic-sounding, as though channelling someone else’s analysis of what Bown herself has instinctively just gone ahead and done. The comments on her photograph of Björk, however, do seem to carry her tone of voice, modest with a hint of steeliness, providing an insight into the contradictory – and splendidly productive – nature of her methods.

On the one hand, she says, Björk “did all the work.” This is the kind of phrase that is characteristic of Bown when commenting on her own output – the idea that the photographer is there simply to catch the right moment, that it is in fact the subject who will “produce” the image for the photographer to capture. The journalist Andrew Billen, who often worked with Bown on assignment, recalls in Looking for Light that “her great phrase was ‘ah, yes, there you are,’” as if to say that her methods – calm and patient, exploratory but efficient – would unearth what was already present and make it visible. But even in the brief paragraph of commentary on the Björk photograph in Faces, we get the distinct impression that it was rather more complicated.

“You could take a hundred pictures of her and every one would be different,” she says, going on to describe the singer, with acerbic affection, as “very unusual and theatrical.” Bown sensed, when she took that shot of Björk, that it would be the one. It was “quite obviously the best,” she says in Looking for Light, suggesting that she recognised how going some way towards anonymising her subject was the key to revealing her; by dampening down Björk’s theatricality she would uncover something more natural and unforced, something more real.

As with all great artists who claim that what they do is really very simple, Bown’s simplicity – the unassuming woman who turns up to photograph a celebrity, spends ten minutes on the task, shooting one or two rolls of film at most before leaving as quietly as she arrived – seems less and less simple the more you look at it. “I was self-effacing and apologetic,” she recalls in Looking for Light; “I wasn’t threatening.” Friends and former colleagues speak affectionately of how, particularly when she became something of a celebrity herself, she often had no idea who the famous people were whom she was photographing, or what they were famous for. No doubt this version of Bown is accurate as far as it goes, but there is also a strong impression of a myth being built up and reinforced until it takes on its own life.

Other comments, by Bown and others, suggest an approach that was rather more deliberate, a feigned unworldliness designed to lower the defences of her subjects. “She was good at putting people at their ease,” says the journalist Polly Toynbee, recalling the occasions when she worked in tandem with Jane Bown in the seventies. “She lulled them into a sense of false security,” says Gary Woodhouse, who was picture editor at the Observer during much of Bown’s tenure. But however deliberate she may have been in her strategies, the “sense of security” that Bown instilled in her subjects was not false.

They were right to trust her. Her portraits do not trap people, or trip them up. Neither do they flatter; instead they convey the sense that we the viewers are seeing them truly, whether or not they are looking directly into our eyes. (Only two people, she says, ever objected to her version of them; the novelist and journalist Martha Gellhorn, and Svetlana Stalin, who felt Bown made her look like a frog.)

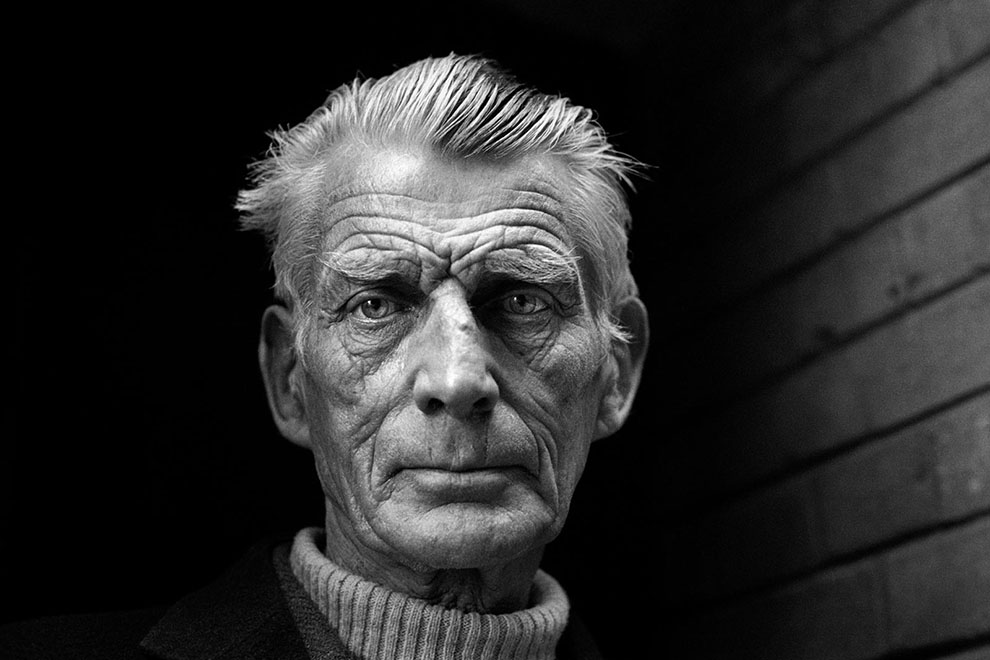

Though much is made of Bown’s quality of human sympathy, and her ability to connect with her subjects even in the brief time that was frequently allocated to her, it is something of a paradox that some of her best images were obtained when the session did not go at all well. Her most famous portrait, the one that appears at the top of this article, is of Samuel Beckett. Taken in 1976, it shows Beckett full-face, with lips set, his eyes looking not-quite-directly ahead. The picture glows with the multiple tonal variations of Bown’s beloved black-and-white. Beckett’s silver hair seems almost over-lit, giving the impression of some kind of natural geological formation rather than mere hair. The Auden-like creases in his skin make him if anything more rather than less handsome. He was, Bown recalls, deeply uncooperative and ungracious, allowing her time for only three shots – in the end she managed five before her time was up. With one of those shots she hit what she sometimes refers to when discussing her photographic methods as the “jackpot” – the Björk-like moment when she knew at once that she had what she was looking for. It is both her best-known photograph and the photograph that defines Beckett.

As the title of Dodd and Whyte’s film suggests, light was everything to Bown, as perhaps it is for most photographers. But she pursued light with an unusual degree of single-mindedness. Famously, Bown never used a light meter, instead checking the available light by looking at the way it fell on the back of her hand. If she was concerned that it might be getting dark by the time she arrived at her assignment, or that the location might not have access to sufficient natural light, she might take along a 150 watt bulb to fix into an obliging table lamp. Or she would, according to Andrew Billen, sometimes bring along her own Anglepoise lamp, thrust into a shopping bag to be drawn out as required. These stories of the bulbs and the lamps seem to sum up her approach – artisanal and low-tech, responding to the moment.

She would buy her cameras secondhand and keep them for ages, feeling no particular need to upgrade or to try out the newest model. In a way she kept on taking the same sorts of pictures for fifty years or more, eschewing phases or periods or distinct shifts in photographic direction or any tendency to adopt the latest technical breakthrough. Bown stuck to the rails, in the words of photographer Don McCullin, doing what she knew best, resisting any temptation she might have felt to seek out new and radically different kinds of subject matter. The co-director of Looking for Light, Luke Dodd, who has spent recent years helping to collate the vast repository of Bown images as archivist for the Guardian/Observer, recalls in his introduction to a book of her photographs, Exposures (2009), that “she once told me how she thought it impossible to take a bad picture abroad.” Dodd interprets the comment as “acknowledging the easy exoticism of images from other cultures.”

It is also a kind of coded warning on Bown’s part, not to take too literally what she has often said elsewhere, that the subject makes the photograph. Sometimes too much choice – the availability of ever more interesting or unusual subjects to photograph, using ever more inventive methods and techniques – is a constraint on creativity rather than an artistic liberation. It was important to Bown’s success as a photographer that she rarely chose her own subjects – most of the time she was on assignment, photographing what she was told to photograph. This regular but not overly demanding pattern of work – two assignments or so a week, often in people’s homes, or in hotel hospitality rooms that became very familiar to her over the years – seemed to fire her creativity rather than dull it.

She had her methods – her rails, as McCullin calls them – and she stuck to them, sometimes repeating devices or motifs to get what she wanted. Her superb portrait of the actress Diana Dors, for example, taken (or “made,” to use Bown’s preferred term) in 1970, echoes a studio portrait of a “Mrs Gestetner” from twenty years earlier. In each of the portraits (they both appear in Bown’s book Faces) the subject is shown touching the end of a string of pearls she is wearing, as though she is actively participating in the creation of the composition.

The impression of human depth in these photographs of women in pearls comes partly from the combination of artifice and naturalness. Dors has adopted a pose, holding on to those pearls with forefinger and thumb, in a way that conveys deliberateness and forethought. Yet the overall impression is one of naturalness and vulnerability. In photographing celebrities, Bown was engaging with people who knew the rules of the game, people who were difficult to catch “off guard.” It is one of her great strengths as a photographer: the fact that she did not attempt anything so underhanded as to trick her subjects. As Patricia Holland puts it, she does not look for “that crude moment of exposure that some photographers go for.” Rather she is able to draw out, in image after image, the qualities of naturalness and humanity that can be found within the poses that all of us, celebrities or not, instinctively adopt when we know we are being photographed.

In Looking for Light and elsewhere, Jane Bown refers to her career as having come about by accident. The stories, as such stories do, hone themselves by repetition. In recognition of her wartime service in the Women’s Royal Naval Service, she was offered a grant to study for two years in order to gain a professional qualification. Unsure what she wanted to do, she took up the suggestion of a friend to “try photography,” studying under Ifor Thomas who was, along with his wife Joy, an inspiring and influential teacher at the Guildford School of Photography in the postwar period. A picture editor admired Bown’s portfolio, particularly a disconcertingly close-up photograph of a cow’s head, in which an eye dominates the frame rather like the eye in Buñuel’s early surrealist film Un Chien Andalou (1929). Before long, says Bown with typical self-depreciation, “I found myself working for the Observer.” Her long association with the Observer, and those increasingly regular assignments to photograph famous people that it entailed, has inevitably come to define her work.

But the people Bown photographed during her career were not always famous, and often the photographic subject did not include people at all. “When I first started I used to photograph funny things,” she has said, “like cabbages and snow.” In 2007 the Guardian staged an exhibition of Bown’s lesser-known work entitled, a bit cutely, The Unknown Bown, using images drawn from its Bown archive. In her introduction to the exhibition catalogue, Germaine Greer remarks admiringly that “it goes without saying that Bown never uses flash,” the clear implication being that Bown herself is never flash, never one to be seduced by special effects or tricksy lighting – nor, by extension, by the easy lure of celebrity, in herself or in others.

Her early, non-portrait work, much of it dating from the 1950s, is particularly effective at conveying a kind of romantic down-to-earthness, the cabbageness of a cabbage, the leekness of a leek or the snowiness of snow. This quality remained in the portrait photography that, from the early sixties, she was increasingly to concentrate on. “She has no truck,” says Greer, speaking of this later work, “with the generation of glamour images, and hence her portraits seem truer than those of other photographers.” One of Bown’s great strengths is the ability to photograph people – people whose biographies lay claim to some kind of distinction – in such a way as to humanise rather than either glorify or undermine them, to take her subjects, as it were, at face value.

Looking for Light captures Bown’s self-effacing single-mindedness as a photographer, to the extent perhaps of over-emphasising her lone way of operating. In fact, as we learn from snatches of interviews, her early and complex family life – she was “illegitimate,” without knowing for many years who her father was – led her to place a particular value on relationships and particularly on family life, her own and other people’s. One of the reasons she stayed so long at the Observer – her entire career, in fact – was that she regarded it as family.

An aspect of her approach to photography that is not much explored in the film is the effect on her work of the practice of working “in tandem,” the journalist and the photographer sent out together on assignment. Often Bown had to stake out her ten minutes where she could, at the beginning or the end of the interview. (Though as Bown’s own fame grew, people’s attitudes changed; her colleague on the Observer, Nobby Clark, tells a tale of being sent as a last-minute substitute for Jane Bown, only to be greeted with extravagant disappointment by the judge who was the subject of the shoot.) Sometimes, if the journalist and the interviewee were both agreeable, Bown would sit in on the interview and catch her subject in mid-flight. Her portrait from 1977, of Mick Jagger laughing, was obtained in this way. “Shots of people laughing do not often work,” she commented, “but I like this one.”

Among Bown’s professional partners at one stage of her career was John Gale, a former foreign correspondent who was later assigned to duties closer to home, including background features and celebrity profiles. Gale, referred to briefly in Looking for Light as “a big, jokey man,” was, like Jane Bown, someone for whom, despite his wild ways, family was paramount. His account of a half-year-long journey through Africa, Travels with a Son, was published in 1972, only two years before his death by suicide. Travels with a Son – the “a” in the title hints at Gale’s quirky point of view – is a movingly unsentimental depiction both of Africa and of his own relationship to his family.

Earlier, in 1965, Gale had produced an autobiographical volume, Clean Young Englishman, which chronicles among other things his flights of derring-do as a foreign correspondent, and the later onset of madness. It contains, towards the end, a single reference to Jane Bown, with whom he had been sent on an otherwise unexplained assignment to Blackpool. (“You knew,” says Gary Woodhouse in Looking for Light, “that if you sent them out together you’d have got something”):

One sunny afternoon we walked down the pier and watched fishermen catching plaice.

“See that man over there in a baseball cap and glasses?” I said to Jane. “He looks just like Epstein, doesn’t he?”

Jane agreed. She had met Epstein several times.

We walked back from the end of the pier, and by the turnstiles we saw an evening paper hoarding: “Epstein dead.”

The man that looked like Epstein had vanished.

In Jane Bown’s beautiful portrait of Jacob Epstein, taken in 1958, not long before he died, the sculptor is shown in his studio, where he is kept company by a variety of heads in progress. He is wearing a cap, as was his habit. It would be nice to have on record more of the conversations that Bown and Gale engaged in while on assignment together, of likenesses and caps and the art of catching the essence of someone before they vanish. •