The United States possesses the world’s oldest surviving democratic constitution — a constitution that eloquently endorses liberty and pioneered the separation of the legislature, the executive and the courts. Over the second half of the twentieth century its standard of living was the highest in the world, and it was a leader in bringing cars, refrigerators, television sets and other goods to a growing proportion of consumers. With the most important concentration of research and development in the world, it was also a technological powerhouse.

In key respects, though, the reality of life in the United States no longer matches the reputation. In some respects, the country has become less dynamic than several of its peers and the living conditions of its people nearer the middle rank, or worse, among affluent democracies.

One sign of this shift comes from the Human Development Index, which was created by the UN Development Programme to measure not just economic wealth but also the broader wellbeing of national populations. The HDI measures three central dimensions of human development — longevity, education and material comfort — on a decimal scale, with 0 as the lowest score and 1 the highest. In 2015 the highest-ranking countries were Norway, on 0.949, and Australia and Switzerland, both on 0.939.

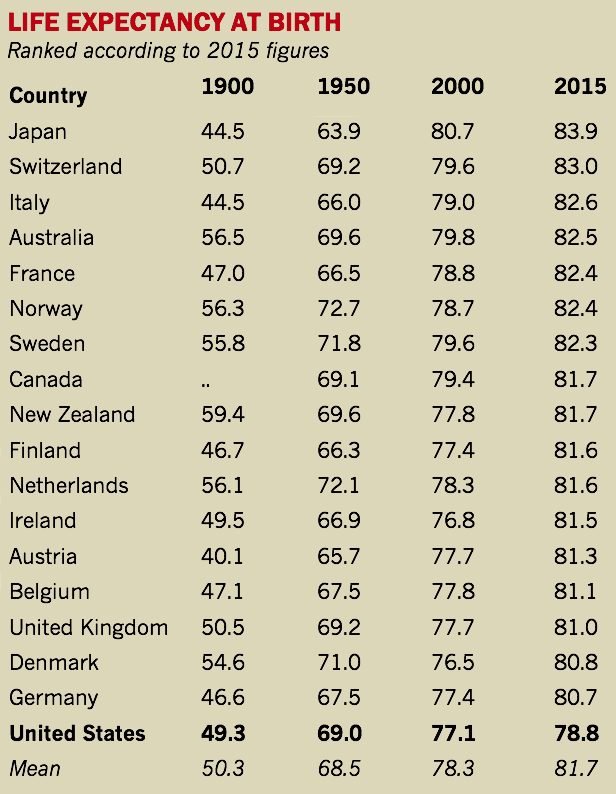

Figures for 1900 are from United Nations Statistical Yearbook 1955. (The Netherlands figure is for 1910.) Figures for 1950 from United Nations World Population Prospects, 1996 revision. Figures for 2000 from US Census Bureau International Data Base. Data for 2015 is from Pensions at a Glance, OECD, 2017, and G20 data.

Especially revealing is the annual rate of change over the quarter-century from 1990 to 2015. Among eighteen comparable democracies, the United States had the slowest increase, just 0.27, compared with a mean of 0.49. As a result, it was overtaken by several other countries and slipped from second to tenth place.

A key reason for this relatively poor performance was an only modest improvement in life expectancy among Americans. Life expectancy lifted dramatically in the eighteen countries during the twentieth century, and was still improving in the first decade and a half of the twenty-first century. By 2015, the figures for the eighteen countries were closely grouped around 81.7 years. The highest was Japan and the lowest was the United States, the only country to record a figure below 80. Its rise was also the lowest during that period — 1.7 years compared with a mean of 3.4.

Worse was to come. In each of the next three years life expectancy in the United States actually fell. The decreases were small — totalling 0.3 years between 2014 and 2017 — and a rash of possible explanations has been offered, including opioid addiction, suicide, the cost of healthcare, rising rates of obesity and economic hardship. It may also have been a temporary blip, but it is a clear turnaround from a long period of growth.

Not entirely coincidentally, the United States is also the most unequal of the eighteen democracies by far. Several democracies became less equal over the past quarter-century, reversing the trend in the decades after the second world war.

Inequality may also be contributing to the United States’s consistently mediocre performance in the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, tests. Held every three years since 2000, PISA examines fifteen-year-old students on maths, science and literacy skills. Conducted in seventy-two countries in 2015, the scores were scaled so that the mean for the thirty-five OECD member countries was 500. American schoolchildren averaged below 500 in all three domains, but were particularly poor at maths, scoring just 470, a distant last among the eighteen most comparable democracies.

The United States is still among the world leaders in research and development, with high scores on innovation and a record of adopting emerging technologies early. But inequality is pertinent here, too. Although the country played a central role in the development of the internet, for example, the proportion of the population who were internet users in 2016 was the second-lowest among the eighteen countries, ahead only of Italy. No other country among the eighteen had a higher proportion of households without broadband.

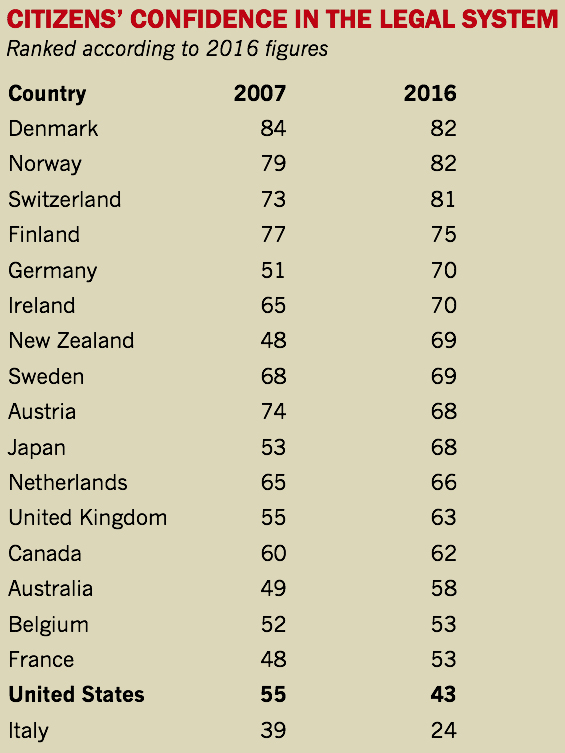

Alongside these objective measures, a nunber of subjective indicators suggest a growing alienation. Apart from Italy, American citizens had the least confidence in the legal system — 43 per cent — among the eighteen nationalities, compared with Australia’s 58 per cent, an eighteen-country mean of 64 per cent, and Denmark, Norway and Switzerland all scoring above 80 per cent. The figures for the United States and Italy also declined more sharply over a decade in which many countries showed increased confidence.

Source: Government at a Glance, OECD, 2017

Americans were also unusually suspicious of the media. Trust was greatest in Finland (62 per cent), the eighteen-country mean was 45 per cent and Australia came in at 42 per cent, but the United States languished at 38 per cent. It also recorded the highest proportion of citizens (31 per cent, compared to an eighteen-country mean of 17 per cent) who say they have been exposed to “fake news.”

None of this portends dramatic collapse, and several other areas testify to the continuing strength of the United States. But a combination of stagnation in certain areas long presumed to be improving, worsening inequality becoming more socially dysfunctional, and increased political alienation suggests a malaise that will challenge whoever wins in November. •

All the data in this article comes from How America Compares, published last month by Springer. The book also features detailed data across many other areas.