A couple of decades ago I wrote an honours thesis about electoral behaviour at Australian constitutional referendums. It was two years after the Hawke government’s set of four dismal failures in 1988, and the record stood at eight successes from forty-two attempted amendments. Since then a couple more, in 1999, have taken the total to eight out of forty-four.

My chief (and unsurprising) finding was that support from the federal opposition of the day was necessary, though not sufficient, for success. This was simply a matter of historical record.

The counter-argument – that sensible proposals naturally attract agreement at the political level while radical or simply dud ones will be opposed – was not supported by the evidence. Content was generally secondary to the political climate and the parties’ positions.

In 1988, for example, John Howard’s shadow cabinet voted to support two and oppose two of the government’s proposals, but was overruled by the joint Coalition party room. On referendum day “yes” votes ranged from 30.6 to 37.4 per cent (and “no”s from 62.6 to 69.4). The four questions dealt with very different topics, so perhaps it could be said that 7 per cent was the extent to which the subject matter made a difference.

In 1974 the Whitlam government held a referendum to ensure elections for the two houses of parliament were always simultaneous. It was opposed by the opposition and received 48.3 per cent support. Three years later Malcolm Fraser’s government tried one, this time with Labor backing, and it managed 62.2 per cent “yes” (but still failed because it didn’t get a majority in a majority of states).

Can a pattern be detected in all of this? Way back in the 1920s, at a royal commission into the Australian constitution, a historian called A.C.V. Melbourne had already detected a logic to how constitutional referendums fared: “active supporters [of political parties] vote along party lines; the rest say no.” Experience since then has rarely contradicted this formulation.

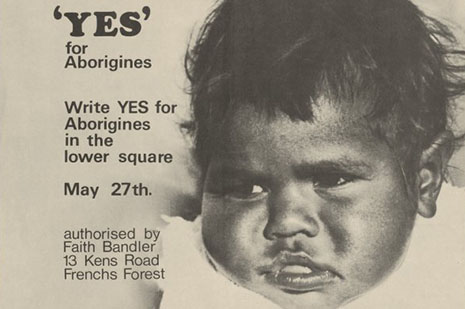

There was, however, one pesky pair of referendums that refused to follow these rules, one pair that proved the exception to the rule. Put to a vote on the same day, the two illustrated democracy working as it is supposed to, with the actual content making a big difference and, in the case of one, sweeping aside the official party position.

It was in 1967, when the Holt government, with the support of Labor, put the two proposals to Australian voters. They read:

Do you approve the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution entitled – “An Act to alter the Constitution so as to omit certain words relating to the People of the Aboriginal Race in any State and so that Aboriginals are to be counted in reckoning the Population”?

and

Do you approve the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution entitled – “An Act to alter the Constitution so that the number of members of the House of Representatives may be increased without necessarily increasing the number of Senators”?

The first has gone down in history as the most popular proposal ever, with 90.8 per cent support across the country; it sits at or near the top of our collective knowledge of Australian referendums. What the vote was about is widely misunderstood, but its symbolism remains potent.

The second, now largely forgotten, would have tampered with one of the tenets of federation. Despite the official government position, sections of the Coalition at federal and state level campaigned against it, and the “yes” option was supported by just 40.2 per cent.

The 50.5 per cent difference between the two is easily the biggest on record. Since federation, the average gap between smallest and biggest “yes” vote (where more than one question was concurrently put) has been 8.9 per cent. The 1967 result showed that what’s being voted on can actually matter. (The substance also mattered in 1999, but in that case – when Australians voted on the republic and a new constitutional preamble – there was no official government position.)

Now, well into the twenty-first century, come plans for another referendum involving Indigenous Australians, this time proposing some sort of recognition that people were actually living here before Europeans arrived. What are the prospects of success?

Indigenous leader Noel Pearson has said that while the vote forty-seven years ago “can be viewed as providing a neutral citizenship for the original Australians… [w]hat is still needed is a positive recognition of our status as the country’s Indigenous peoples, and yet sharing a common citizenship with all other Australians.”

This is obviously a more ambitious task. While the 1967 referendum eliminated a particular constitutional discrimination, the mooted one will reintroduce another. The most important effect of 1967 was giving the Commonwealth power over Indigenous affairs, but that wasn’t widely understood by voters and, as can be seen above, wasn’t mentioned in the wording.

I was too young back then to pay attention, but I do know that the widely accepted “hows” and “whys” of past political events tend to be incomplete at best and total fiction at worst. If anyone today is trying to replicate that campaign they should stop it right now.

Some people at the coalface of the discussion today don’t seem to fully grasp what’s involved. A few “minimalists” advocate eliminating references to “race” in the document and leaving it at that. That does sound appealing, and surely only a small minority of Australians would object.

If only it were that simple. “Race” is currently found in two places in the document. One (s 25) could easily go, according to constitutional experts, with no practical repercussions. But not so s 51xxvi (the “race powers”). As constitutional lawyer George Williams has written, repealing that sub-section “could undermine the validity of existing, beneficial laws already enacted under the power... in areas like land rights, health and the protection of sacred sites.”

Some may long for just this development, but for anyone who doesn’t, something else has to be inserted in its place, mentioning Indigenous Australians and, perhaps, their “advancement.”

From that point, acknowledging tens of thousands of years of civilisation in Australia before European arrival is a small extra step. Yet most of the advocacy frames this, rather than the need for Australia in the new millennium to remove references to “race” from its founding document, as the raison d’être of the exercise.

And many Australians, and not just those who wish Indigenous people ill, would object to the reintroduction of specific references to people’s… well, race. Yet without doing that, the word “race” can’t be taken out.

Other discernible currents in the history of constitutional referendums also point to the complexity of steering through a “yes” vote. Conservative opposition leaders tend to lack the authority to support the ones Labor governments put up, even if they are personally inclined to. Opposition to constitutional reform resides at DNA level in much of the party room and the wider conservative movement; politically, joining the “no” campaign is the path of least resistance.

That’s why the Coalition in opposition has opposed nearly every Labor referendum (on the exception, in 1946, they ran dead). A textbook example was provided last year when Tony Abbott disowned the local government cause at the eleventh hour. Prime ministers (on either side) have more power than opposition leaders to drag their sides along paths they are otherwise not inclined to take.

Meanwhile, Labor in opposition has usually been in favour (the Coalition’s proposed ban on the Communist Party in 1951 being an obvious exception) for the converse reason: they instinctively favour amendment. So, like Nixon going to China, this or any constitutional reform will more likely succeed under Abbott than Gillard – or any Labor prime minister.

But how to maximise the chances of success?

Well, another clear pattern from the voting record involves whether a referendum is held at a general election or separately. The very worst performers were held mid-term and lacked bipartisan support. Those put with an election, and opposed by the opposition, tended to lose respectably, garnering votes similar to the government’s primary vote.

In A.C.V. Melbourne’s equation, we might see this as party loyalty being consolidated at election time. And during election campaigns, referendums sit neglected in the background, behind the more urgent fight for government.

But achieving bipartisan support is even more difficult when there’s a general poll on the horizon. At referendum after referendum, opinion poll support has receded as the topic is picked apart by opponents, including the officially funded “no” case.

Already parts of the conservative movement are agitating against Indigenous constitutional recognition, and if the referendum is held before the next election, even with bipartisan support, it could become quite heated and even nasty. Given the ever-decreasing levels of enthusiasm for both sides of politics, Melbourne’s equation would probably add to less than fifty. And given Abbott’s stubbornly poor standing in the electorate, he might, once again, walk away from a lost cause.

The best chance of success, provided bipartisan support was locked in, would be a referendum held with the 2016 election. Then the topic would remain largely unmolested.

Sliding through under the cover of night doesn’t sound like much to celebrate. But after it’s done, we can pretend it happened another way. That’s what we usually do with political history. •