Part of our collection of articles on Australian history’s missing women, in collaboration with the Australian Dictionary of Biography

Kathleen Ussher’s story of reinvention stretches across much of the twentieth century. She was, at various times, an illustrator, author, civil servant, hospital orderly and Hollywood journalist. Her career took her into literary and cultural circles, connecting her to a generation of successful Australian women, some of whom became prominent historical figures. Most, though, including Ussher herself, have largely disappeared from the historical record.

Florence Emily Kathleen Ussher was born on 19 August 1891 at New Farm in Brisbane. She came from an adventurous family: her father, Captain James Ussher, was a Torres Strait pilot, helping navigate ships through the reefs, and her mother, Florence Eleanor Ussher, escaped the Great Flood of 1893 with Kathleen in one arm and Kathleen’s older sister, Lorna, in the other. The family left Brisbane not long after the flood, and Kathleen was raised primarily in Sydney.

There, from 1901 to 1907, she attended Shirley, a demonstration and training school for girls. Founded by Margaret Hodge and Harriet Newcomb, it aimed to “give the pupils an education which shall develop individual power.” Kathleen epitomised those goals, excelling in French, captaining the swimming team, and becoming school librarian. After Kathleen’s father died unexpectedly on Thursday Island in 1904, Florence Ussher supported her daughters’ careers unconditionally, encouraging them to pursue the interests that would later take them across

the world.

After leaving school, Kathleen briefly joined the public service as a shorthand writer and typist, while continuing to attend drawing classes at night. During this period, her mother and sister moved to Leipzig, Germany, for Lorna to attend the Royal Conservatory of Music. Kathleen joined them in 1912, briefly studying at the city’s Royal Academy of Book Illustration before leaving for London in 1913 to pursue art at Goldsmiths College.

In 1914, she joined Hodge — the former head of Shirley — and Dorothy Pethick on their lecture tour to North America, where they served as unofficial representatives for the Australian women’s suffrage movement. After their arrival in New York in late March, she acted as secretary and press correspondent for Hodge as they visited New York, Chicago and Toronto. Following the tour, she began studying book illustration at the Art Institute of Chicago.

As the first world war continued, Ussher paused her studies and, in May 1915, left for London, where she became embedded in the war effort. During the day she worked with the Royal Australian Navy as a secretary, organising the paperwork for the construction of the HMAS Adelaide; in the evenings she volunteered with the Women’s Reserve Ambulance; on weekends she worked in munitions factories. “Kath’s patriotism,” wrote her friend Miles Franklin, “leads her to go and make munitions on Sundays for a most unpatriotically low wage after working all the week doing a man’s work, for which she is also paid less than a man and jealously kept from expansion.”

In mid 1917 Ussher joined the Scottish Women’s Hospitals alongside Franklin and another friend, Nell Malone (also profiled in this collection). The enduring friendship between these three women is chronicled in Ross Davies’s book Three Brilliant Careers (2015). Ussher and Malone both served with the Girton and Newnham Unit — named after two women’s colleges at the University of Cambridge — of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals in Salonika. Ishobel Ross, another of the Scottish Women, described Salonika as “a most exciting place,” crowded with white houses with Venetian shutters, small stalls spilling out into the streets, and soldiers of every nationality. With their grey uniforms, Scottish Women became affectionately known to their patients as “little grey partridges.” New arrivals soon shortened their skirts to move through the wards. Staff were to call one another by their surnames, although an exception was made for Ethel Hore.

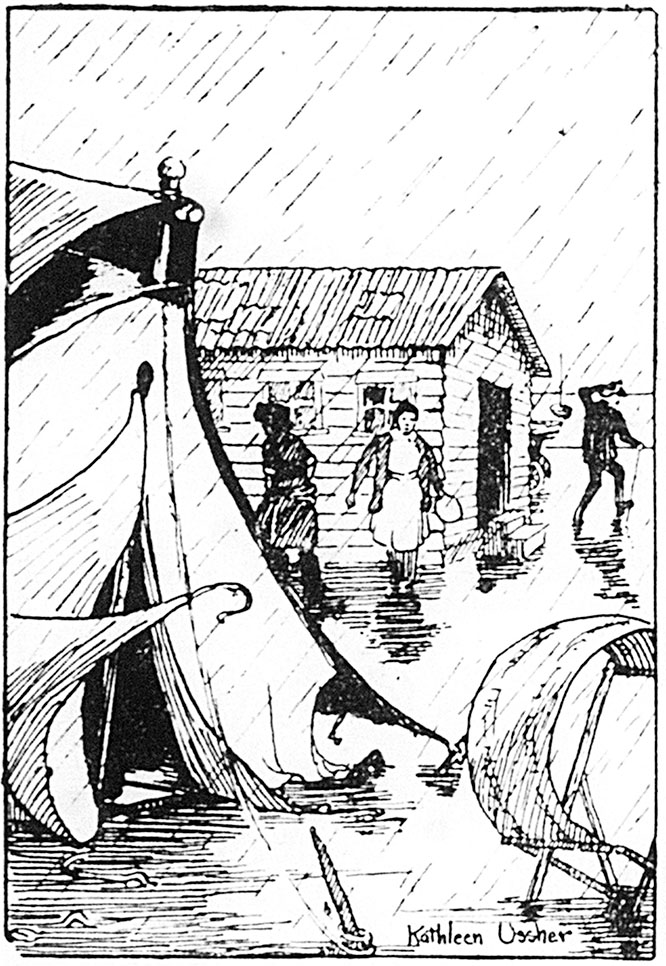

One of Kathleen Ussher’s illustrations — captioned “When the Navy withdrew to a dry place at sea” — from “War Wanderings of an Aussie Girl,” a chronicle of her adventures published in Aussie magazine in February 1921. Australian War Memorial

In 1918, after finishing her term with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, Ussher applied to join the Women’s Royal Naval Service, popularly known as the Wrens. She accepted an offer of a transfer to Gibraltar, making her one of the first Wrens to be sent on active service. This reflected something of a family tradition: in addition to her father being a sea captain, her great-great-uncle, Admiral Sir Thomas Ussher, had escorted Napoleon to the island of Elba.

Following her return to Australia, Ussher served as secretary of the Ex-Service Women’s Club while continuing to pursue her interest in art. In 1921, she designed a postcard for the Centre for Soldiers’ Wives and Mothers promoting a proposed memorial drinking fountain at the wharf gates at Woolloomooloo. That same year, she also took part in an exhibition of “cabinet pictures and craftwork” organised by the Society of Women Painters, alongside Australian female artists including Hilda Rix Nicholas, Hedley Parsons and Dora Ohlfsen-Bagge. In 1925, she provided the illustrations for Gum-trees, a collection of seven Australian songs.

Ussher’s attention returned to North America, and she joined her mother and sister in Southern California, where she reinvented herself again, working as a Hollywood journalist with a regular byline in the Sydney Mail. Although her column, “Behind the Silver Sheet,” became widely known after she interviewed the popular American actor Mary Pickford, Ussher focused mainly on the rising careers of Australians in Hollywood. She kept her readers in Sydney informed about the activities of then-familiar actors like Louise Lovely, Mae Busch and Snowy Baker. She continued to interview screen stars throughout the decade, but broadened her scope to include Australian novelists and other subjects after she moved to London sometime before 1930. This expansion included a 1931 profile of Henry Handel Richardson — the pen name of Ethel Florence Richardson — which sparked an enduring literary friendship between the women.

Alongside her journalistic career, Ussher began to publish her own books. These included The Cities of Australia, her contribution to “The Outward Bound Library,” in 1928, and Hail Victoria!, a centenary retrospective, in 1934. Both were well received, although a critic did suggest that “possibly her enthusiasms have led her to place our cities on a rather higher plane than is entirely just.”

The latter stages of Ussher’s life are less clear. Following the second world war, she worked in London in the reference library of the Central Office of Information, the successor to the Ministry of Information. She was then appointed to the organisation planning the Festival of Britain, the national exhibition and fair that extended across the United Kingdom in 1951. She remained in England for the rest of her life.

Kathleen Ussher died in England in 1983, aged ninety-two, after a life spent promoting Australian interests around the world and supporting others, particularly other Australian women. Her varied career is best described in her own words, describing her wartime service in London: “Well, you felt like you were doing your bit. That is all there was to it.” •

Further reading

Three Brilliant Careers, by Ross Davies, Boolarong Press, 2015

Her Brilliant Career: The Life of Stella Miles Franklin, by Jill Roe, HarperCollins, 2008

A History of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, by Eva Shaw McLaren, Hodder and Stoughton, 1919