When minor health concerns force us to take a couple of days off work, the downtime can give us an opportunity to calmly consider potentially life-changing decisions. After all, there’s nothing enjoyable about being pushed aggressively for quick answers to big questions.

That’s how it has panned out for Malaysia’s king, Sultan Abdullah of Pahang. On 23 September, the Palace announced that although his condition was “not worrying” the king was undergoing treatment at the National Heart Institute after complaining of feeling unwell.

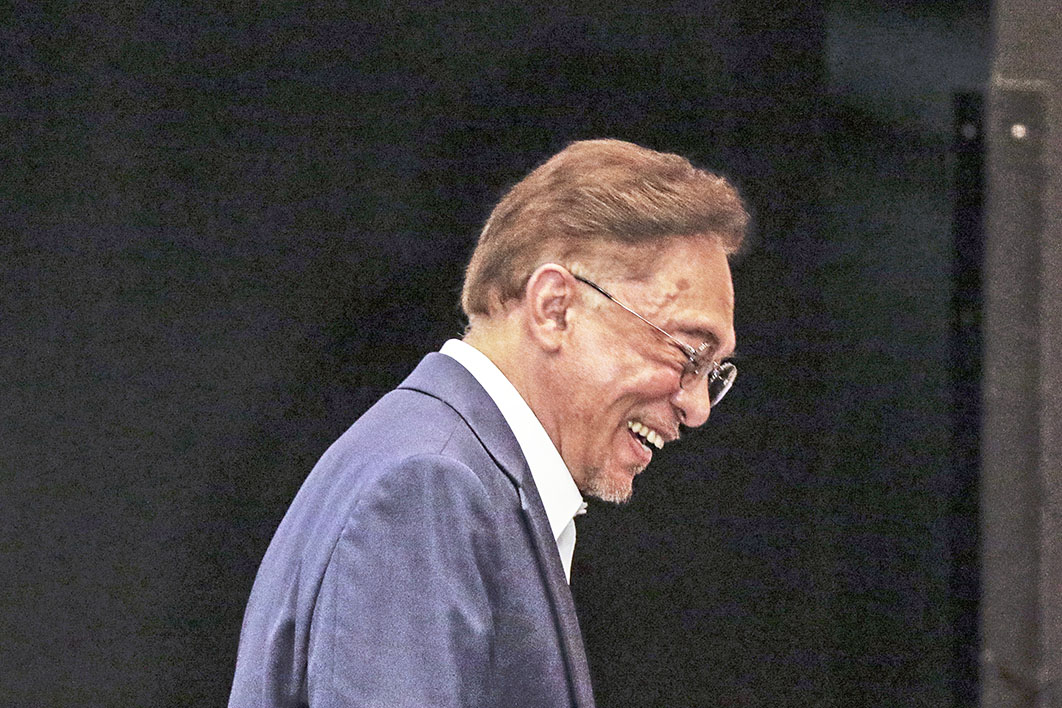

That same day, Anwar Ibrahim, leader of Malaysia’s People’s Justice Party and a key figure in the short-lived Pakatan Harapan (Pact of Hope) government of 2018–20, announced that the country’s latest government, led by prime minister Muhyiddin Yassin, was on the ropes. Claiming he now had a “strong, formidable” parliamentary majority, Anwar declared that he was ready to lead.

“With a clear and indisputable support and majority behind me, the government led by Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin has fallen,” Anwar declared. He didn’t reveal the number of MPs supporting him, however, or release any of their names. He would speak to the king first, he said, and wished him a speedy recovery.

On 25 September, the Palace announced the king would need to spend a week under observation in hospital. “So, until then, he will not have any meetings,” the Palace comptroller told the media. A few days later came more information: the king had food poisoning, and an old sports injury needed attending to. With the royal encounter postponed until later this week, it is unclear who currently holds a majority in Malaysia’s federal parliament, or how the numbers might change between now and then.

“Anwar is the perpetual shaft, lah,” a friend said to me on the evening of Anwar’s announcement, referring to Anwar’s history of repeatedly being shafted in his bids for the top job.

Anwar has been at the centre of a series of power struggles for more than two decades now — struggles he has invariably lost, despite claiming to have the necessary support. In each case the numbers either have shifted with the political wind or weren’t falling Anwar’s way in the first place and he was gambling they would move towards him once he made the claim.

This time, too, Anwar’s arithmetic has been disputed by several leading government figures, including Muhyiddin, who pointed out that he remains prime minister until proven otherwise by “the process and methods determined by the federal constitution.”

“Without this process,” said Muhyiddin, “the statement by Datuk Seri Anwar is only a claim.” Chiming in, Bung Moktar Radin, a Muhyiddin partner in the federal government and an MP from Sabah state, argued that Anwar was simply engaged in “a ploy to disrupt the state election” that would take place three days after Anwar’s announcement.

Others from the parties that make up Malaysia’s current government also pointed out that Anwar had made such claims before. “Keep dreaming,” said energy and natural resources minister Shamsul Anwar Nasarah. Nevertheless, Anwar’s coalition partners announced their support for his bid, although the Democratic Action Party attached the caveat that its support would only follow if he truly had the numbers.

Even more surprisingly, UMNO’s Zahid Hamidi told the media that many of his party’s MPs supported Anwar, triggering speculation that allies of former prime minister Najib Razak might be trying to secure Anwar’s agreement to cease investigating the multibillion-dollar 1MDB scandal in return for the prime ministership. Najib and a number of his UMNO allies have been the subject of court actions in Malaysia and the United States over the affair, which played a key role in the change of government in 2018.

Could Anwar accept such a deal? A separate development might hold a clue. Just two days earlier, on 21 September, he failed to convince the Federal Territories Pardons Board to strike out a legal suit challenging the pardon he received just days after Najib was toppled. Relating to a conviction for “sodomy” (as Malaysian law calls it), the pardon allowed Anwar to contest a subsequent by-election and join the historic yet short-lived Pakatan government, the first to take government from the UMNO-led Barisan Nasional (National Front) in the nation’s history.

Without the pardon, Anwar’s conviction prevents him from sitting in parliament. If it is reversed, he might have to serve out the rest of his prison sentence. After decades of failed attempts, his hope of becoming prime minister could be dashed forever.

Pakatan’s collapse in February this year marked the latest stalling of Anwar’s leadership momentum. Key allies see him as too “liberal” and too soft on Malaysia’s cultural minorities, and as scaring away voters among the Malay Muslim majority. But he has been distancing himself from such accusations since the very moment of this month’s announcement. “We are committed to uphold the principles of the constitution that recognises the position of Islam, the sovereignty of Malay rulers, to uphold the position of Malay language as the official language, as well as the special position of the Malays and Bumiputera as well as give assurance to defend the rights of all races,” he said.

Despite such assurances, Anwar’s allies hardly came rushing to his side to support him. As if to keep him guessing, the Democratic Action Party pointed out that if he failed in his bid then his Sabah ally, Shafie Apdal, might become prime minister instead, especially on the back of a potential win in the Sabah state election a few days later. Shafie’s name had come up in the past, not least as a potential circuit-breaker in the rivalry between Anwar and former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad, whose resignation in February 2020 precipitated the Pakatan government’s collapse. Anwar’s daughter, Nurul Izzah, accused the Democratic Action Party of picking over old wounds.

For his part, Mahathir joined in this latest round of elite jockeying with his own claims, pointing out that if Anwar thought he had the numbers then Muhyiddin, who has been governing with only a rumoured two-seat majority, surely did not. But relying on the UMNO defectors to form government was a dangerous idea, said Mahathir, and anyone who did so would find themselves caught in the same trap as Muhyiddin — forced to give UMNO what it wanted to hold on to power, without any guarantees that these new allies would stick around.

By implication, of course, he was suggesting that the individuals, power blocs and parties looking for new alliances should come and talk to him instead.

Observers posted “popcorn” GIFs on Twitter, while Najib opted for pictures of packets of Super Ring, cheesy snacks similar to Cheezels.

Amid this shadow-boxing, on 26 September, Sabah state voters went to the polls knowing their decision would carry federal implications. Speculation had been building that Borneo voters’ resentment towards the Malaysian Federation might affect the way Sabahans would vote. Shafie had been campaigning against Muhyiddin’s allies in the state on the basis that they had toppled the previous federal government after jumping, like “frogs,” out of Pakatan and into the government that replaced it.

But Shafie’s party lost the election and Muhyiddin’s group took a majority of state seats, even winning a dispute with its coalition partners and naming a chief minister ahead of his scheduled appointment by Sabah’s governor. But Shafie remains hopeful that some frogs will jump his way. Depending on how the state — and federal — power struggles of this week pan out, there might be two new governments forming in Malaysia when the king emerges from hospital.

Or there might not. With the Sabah result having gone his way, Muhyiddin might have emerged stronger in the federal bargaining.

Meanwhile, and sometimes lost in the coverage of the internecine power struggles, Malaysia is still dealing with a pandemic, the economic impact of which caused its economy to contract by 17 per cent in the second quarter of 2020. The crisis is further diminishing household incomes that were already running so short after several years of low growth that cash-transfer measures, such as the former Barisan government’s BR1M scheme, have been needed to support household consumption.

In addition to the outrage generated by the 1MDB scandal, it was this low-growth economic environment that made the 2018 pre-election environment so febrile. The latest contraction is the economy’s worst since the Asian financial crisis of 1997–98, an event whose political consequences the nation is still living with. Indeed, that crisis triggered Anwar’s first push for federal leadership against then prime minister Mahathir.

Muhyiddin’s Covid-19 stimulus packages now exceed 17 per cent of GDP, especially after his announcement of a further MYR10 billion in cash assistance and wage subsidies on the same day as Anwar’s leadership challenge.

The pandemic might have provided cover for a host of political moves behind the scenes, and Anwar might yet prove he has the numbers. Yet, as Malaysia’s crisis of elite politics deepens, so too does its economic crisis. And so the various economic and social pressures that Pakatan tapped in its rise to power in 2018, and that Muhyiddin’s government tapped to topple Pakatan, continue to intensify.

Malaysia is going through enormous pain, and whatever new political coalitions emerge from this latest round of manoeuvring will need to focus on resolving it. The country’s coalition politics won’t stabilise in the meantime. •