The Realisms of Berenice Abbott

By Terri Weissman | University of California Press | US$60.00

Eugène and Berenice: Pioneers of Urban Photography

Directed by Michael House | Sit Up Straight Films | US$15

AMONG the works of great photographers there is always one signature image that sits like a monument to their reputation. Think of Ansel Adams’s Moonrise, Hernandez, Arnold Newman’s portrait of Stravinsky at the piano, Max Dupain’s Sunbather or Olive Cotton’s Tea Cup Ballet as examples of single photographs as enduring monuments to the photographer.

Berenice Abbott’s monument is her photograph New York at Night 1932. When Susan van Wyk, curator of photography at the National Gallery Victoria, designed a catalogue for the exhibition Luminous Cities it wasn’t surprising that this was the photo she chose for the cover.

After spending eight years in Paris and Berlin, part of the time under the tutelage of avant-garde photographer Man Ray, and profoundly influenced by the Parisian photographer Eugène Atget, Abbott had returned to New York in 1929. She came back to a city being transformed by the skyscraper building boom and also about to be plunged into the crisis of the Great Depression.

From Atget she had gained a deep feeling for the city as subject. Although she had been doing well as a portrait photographer in Paris she didn’t pursue that form in New York, except when the need to earn money dictated that she take flattering photos of the plutocracy, most of whom she thought to be self-absorbed and uninteresting. Her real interest lay in the city itself and the points where the old was being swept away to make space for the dazzlingly new.

Eugène Atget’s (1857–1927) project in Paris had been much the same – recording the remnants of the ancient city before they were destroyed to make way for the realisation of Baron Haussmann’s dream of creating the most beautiful city in the world (which involved brutally removing the old and displacing the inhabitants). Abbott, who photographed Atget just before he died, bought his archive of negatives and prints and took them back to America. Without her intervention it is possible that they would have been destroyed. She never stopped speaking and writing about the Atget legacy and in 1969 she deposited the treasure with the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

For New York at Night she had to make careful plans. She wanted to capture the moment at dusk when the office lights are on but there is still enough daylight to see the buildings. She decided that the shortest day of the year would be her best opportunity, and she selected a shooting position high up in the Empire State Building. Because she planned a long exposure she needed an evening without wind so that her view camera would not move on the tripod. The result of this meticulous planning and preparation is beyond doubt her monument photo.

When I look at it it stirs in me admiration for her deliberate artistry – she wasn’t one to take twenty-seven spontaneous shots hoping that one might be worth keeping – and for American audacity. The world had never seen anything like these mountain-sized buildings. Possibly no one but Americans could even conceive that it might be possible to construct a building more than 100 storeys tall. The Empire State, Chrysler and Rockefeller buildings were breathtaking then, in the 1920s and 30s, and they still take the breath away.

Abbott’s literary collaborator, and possibly lover, Elizabeth McCausland, interpreted the city images differently. To her they were a record of the destructive power of American capitalism in all its flashy vulgarity. McCausland was that rarest of American characters, a Marxist critic. Sometimes she seems to have imposed more interpretative words onto Abbott’s images than they can bear.

But when it comes to superfluous verbiage she doesn’t hold a candle to Terri Weissman, whose monograph The Realisms of Berenice Abbott piles layers of turgid academese onto photos that are simply isolated frames filled with edges, angles, shadows and light. Abbott herself was an advocate of simplicity and unadorned realism. She didn’t like the prissy pictures of the pictorialists and she had broken completely from the silly extravagances of the avant-garde. She returned again and again in her speeches and writing to the importance of “realism” (her word) in photography. She was a recorder, not a commentator or interpreter.

Weissman’s discussion of Abbott’s simple portraits of the rich and famous is risible. Of a studio photo of Princess Murat, she writes: “This portrait operates outside a merely psychological or psychologising framework in that the plurality of gazes (Abbott’s, Murat’s, the spectator’s) paralleled by a seeming plurality of subject positions (feminine, masculine, both feminine and masculine and neither) situates this work in a social field that extends beyond the visible and beyond the specifics of Murat to a world that remains open to investigation, where there exists no simple expression of one’s self.” In other words it’s a picture of a plain woman who dresses like a bloke and smokes, shot against a featureless studio background.

It’s hard to believe, but New York at Night – one of the greatest photos ever taken, an image that marks Abbott as one of the most important photographers of the twentieth century – doesn’t appear in the book. Perhaps it’s just as well, because the quality of reproductions is poor and they do not do justice to the works that are included.

Fortunately there are many other sources of information about Abbott’s work, among them two documentaries, New York and Paris: The World of Abbott and Atget, screened by the ABC last year, and Eugène and Berenice: Pioneers of Urban Photography, screened at about the same time on SBS and now released on DVD. Watching these two programs, in which the commentary on the photographers’ work is made by art historians and photographers who revere the artists, gives an insight that is completely missing from Weissman’s book.

Eugène and Berenice begins by looking at the extraordinary work of Atget who, even into the twentieth century, continued to carry a twenty-kilogram camera around Paris and then make his prints using the albumen method of coating paper with silver suspended in egg white. The prints were then exposed to sunlight before developing and fixing. As a result his images have an ethereal beauty, enhanced by his practice of shooting early in the morning.

Atget rejected the appellation of artist – he insisted that he was a documenter, taking photographs to sell to painters who needed reference pictures from which to paint. Man Ray was one of the first of the young expatriates to recognise Atget’s photographs as works of art in their own right, and it was he who introduced Berenice to Eugène.

In interview footage in the film Berenice speaks of her work with profound intelligence and simplicity. Her photographic philosophy, if we may call it that without offending her spirit, is: “Whatever you photograph has to be visually important – otherwise you write about it.” In her book A Guide to Better Photography: “Photography is a new vision of life, a profoundly realistic and objective view of the external world… What the human eye observes casually and incuriously, the eye of the camera (the lens) notes with relentless fidelity.” I think she is saying that the “straight” (her word again) photo speaks for itself. Words are superfluous if the photo has done its job. Pompous commentary is an insult to the photographer. I prefer the simple tribute by one artist to another when, in New York and Paris: The World of Abbott and Atget, a British photographer says of New York at Night: “I look at that image and I think, ‘I wish I had taken that photograph.’”

The last part of Berenice Abbott’s working life was spent as a technical photographer in the laboratories of MIT. She said that she enjoyed the work, but she also spoke in private of the hostile male atmosphere in which she was operating. The physicists whose experiments she was photographing found women “difficult” and in any case thought that a few Polaroid snaps would do the job. Yet she produced photographs that are both aesthetically pleasing and at the same time instructive records of laboratory events.

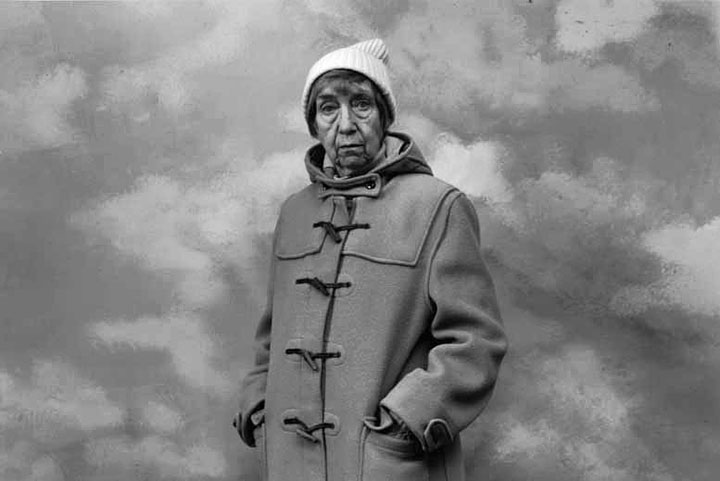

She died in 1991 and is considered, along with Eugène Atget, to be a pioneer of urban photography and an artist without peer in her field. The link between the two photographers is preserved forever in the touching portrait Abbott took of Atget just weeks before he died.

Would-be photographers are warned: looking at Abbott’s photographs might leave you asking, “What is there left to do?’ Or it might be a lesson in the art of photography that inspires you to try harder. •