In the September quarter of 2019, the federal government paid out $3.3 billion to subsidise economic activities for one reason or another. In the September quarter of 2020, it paid out $53.6 billion, or one dollar in every nine dollars of output we produced. Call it JobKeeper.

In September quarter 2019, the government paid out $32 billion to households as welfare payments. A year later, it paid out $48 billion. Call it enhanced JobSeeker.

It wasn’t just JobKeeper and JobSeeker, but they were the real heroes of this week’s GDP figures. Australia’s economy has now moved into recovery, while still remaining fundamentally in recession. In all, the federal government took a breathtaking $73 billion hit to its finances in a single quarter, more than half its gross income, to help the economy back on its feet.

It’s worked, and treasurer Josh Frydenberg was justified in claiming it as a success story. It wasn’t perfect, but it was good enough — along with the success in getting coronavirus under control in all states and territories except Victoria — to power the economy back up.

Business still wasn’t investing — business investment was already at historic lows in 2019, but plunged another 10 per cent in the year to September. But in the September quarter itself, household consumption shot back up by more than 10 per cent in every state except Victoria. And that, despite households saving an incredible 19 per cent of their swollen incomes.

In hindsight, sure, the government overdid the generosity, but it had been misled by panicky epidemiological modelling, and in any case, it was better to do too much than too little. (Of course, it could have done even better by spreading less money among more people, as many pointed out at the time, but that’s another story.)

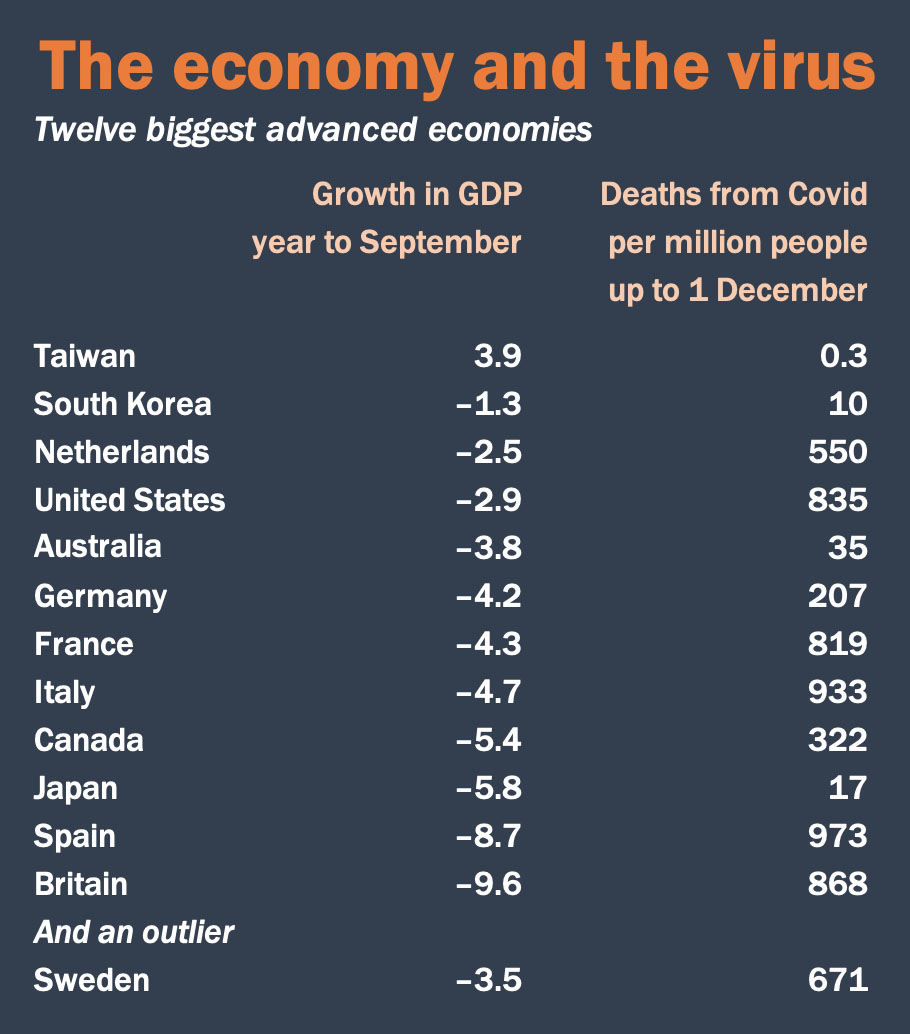

Sources: Eurostat and national statistical agencies (GDP), Worldometers (Covid-19).

Frydenberg went over the top, however, in proclaiming Australia’s performance as a world-beater. Even among the twelve largest advanced economies, we were just average — fifth of the twelve in comparing GDP year on year, but probably seventh or eighth if we had figures for the real bottom line, which is not GDP but GDP per head.

We do have those figures for Australia. Surprisingly, perhaps, the Bureau of Statistics estimates that Australia’s population grew by roughly 250,000 over the year to September, or almost 1 per cent. The fall in GDP year on year was 3.8 per cent, but GDP per head fell by 4.75 per cent, putting us at the back of a small peloton with Germany, France and Italy.

The real world-beater in the advanced world, of course, is Taiwan, where the economy grew by 3.9 per cent while just seven people died of coronavirus in a country with a population almost as big as Australia’s. It is sobering to reflect that this extraordinary democratic success story is now under serious military threat from Xi Jinping’s ambition to retake what China sees as a rebel province. For Xi, from what we read, bullying Australia is a sideshow. Retaking Taiwan is his main game.

One last point on the international comparisons. As the table shows, Taiwan and South Korea have done best both in suppressing the virus — without lockdowns, but with state-of-the-art contact tracing, quarantine and public health measures — and in maintaining economic momentum. Spain and Britain have done worst in both, partly because they are both major tourist destinations, and tourism destinations everywhere have suffered worst.

Otherwise, though, I defy anyone to show how the two sets of figures back up the claim that lockdowns are good for economies. For reasons I for one don’t understand, Australia and New Zealand are hardliners in focusing solely on fighting the virus by whatever means, whereas in Europe and the United States, governments and the public have been far more hostile to locking down their economies.

With luck, the British decision overnight to approve a vaccine for public use is the beginning of the end for this strange episode in world history. But as they say, this is a marathon, not a sprint. Many things have taken us by surprise, and there could be many more before it’s over.

Australia’s claims to be an economic standout were frustrated by the second wave of the virus in Victoria, and the severity of the lockdown the Andrews government imposed to crush it. Victoria was home to 90 per cent of Australia’s coronavirus deaths, 94 per cent of its net job losses (year to October) and, yesterday’s figures tell us, 72 per cent of the loss in economic activity in the year to September.

In the rest of Australia, total spending in the economy fell only 1.35 per cent over the year. Take out New South Wales as well, and demand in the rest of Australia actually rose 0.1 per cent year on year, with the Australian Capital Territory streaking away, and Queensland recording growth. But spending over the year shrank by 3.3 per cent in New South Wales (which was not in lockdown) and by 9.8 per cent in Victoria (which certainly was).

Household spending in Victoria contracted by 16 per cent over the year. Compared with a year earlier, Victorians spent 92 per cent less on trains, trams, taxis and planes, 71 per cent less in hotels, restaurants and cafes, 45 per cent less on buying new clothes, 39 per cent less on using their cars — and a seriously worrying 18 per cent less on going to the doctor, pathology clinic or operating theatre. Doctors have voiced alarm that this means trouble ahead.

Right now, however, that severely suppressed spending means Victoria is likely to come tearing out of the blocks in the December quarter, carrying the nation with it. Consumer spending will need to keep growing fast, because unless the Covid-19 crisis appears to be ending, business investment will recover only gradually — and the federal government’s strategy relies heavily on it.

Whether Australia can meet the government’s ambitions depends on the successful rollout of vaccines, and whether they provide an enduring barrier against this clever little virus. Whatever the outcome, it is now time for the government to spell out its plans for the JobSeeker payment. The Australian Council of Social Service has urged a rise of at least $100 a week to the meagre $40 a day paid to single jobseekers, and a realistic rental allowance to help them stay in their homes.

Frydenberg has to have something to replace the $50 billion in wage subsidies and $18 billion in charged-up welfare payments he handed out in the September quarter. A serious, humane increase in JobSeeker is the missing piece of the government’s policy for the recovery. Without that, there is a serious risk that its plans pull back too much support, too fast.

One last point. The national accounts show no sign yet of any real damage to Australia from any of China’s various acts of economic warfare. In the September quarter, China’s share of our exports grew to a new record of more than 40 per cent, as our exports to the rest of the world shrank. Our barley exports have found new homes at higher prices, raising hopes that other industries targeted by China’s rulers will do the same.

The stakes are rising, however, and firms who had put off developing new markets for their products could be in trouble in 2021. This too could be a marathon. The government cannot back down, and there is no public demand for it to do so. The best we can hope for is that it rules a line under the past, acts with forbearance, discipline and dignity under pressure, helps firms find new markets, and leaves the door open for China to one day resume an economic relationship that had worked well for both countries. •