Early last month, in what was Britain’s worst mass shooting in years, a man named Jake Davison shot dead five people, including a three-year-old girl, in Plymouth. Davison had posted a series of videos online in which he described feeling socially isolated and struggling to meet women, and made reference to “incels” — an online group of men who complain that women are put off by their looks or their low socioeconomic status.

While Davison didn’t identify himself as an incel, his actions echo those of men associated with this movement. In 2014, for example, Elliot Rodger killed six people in a shooting in Isla Vista, California, and in 2018 Alek Minassian drove a rented van through a pedestrian mall in Toronto, killing ten. Each of these men made clear their allegiance to incels.

These killings helped fuel concern about misogynist violence, and particularly violence linked to online forums. As Donna Zuckerberg, who happens to be the sister of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, argued in her 2018 book on the issue, “social media has elevated misogyny to entirely new levels of violence and virulence.”

A newly released report from a global team of researchers led by Manoel Horta Ribeiro backs up some of these concerns, finding that online anti-women groups, including incels and “men going their own way” (men who believe relationships with women are so toxic they are best avoided altogether), appear to be growing. Using data collected from forums like Gab and Reddit, the researchers also found the level of toxicity in the “manosphere” had risen significantly.

Policymakers have also expressed concern. In March this year the director-general of ASIO, Mike Burgess, described how a growing number of extremists no longer fit the left–right spectrum and are instead “motivated by a fear of societal collapse or a specific social or economic grievance or conspiracy.” Incels were among the groups ASIO is taking more seriously, he said.

Despite the new labels, the ideas motivating these groups are not entirely new. They follow on from a longer-standing men’s rights movement that has had significant influence, despite its relatively low profile, in key areas of family policy, particularly during and since the Howard government.

The men’s rights movement originated in the United States, where figures such as Warren Farrell, who was once a prominent male feminist, created a movement to oppose what they describe as “institutional misandry,” or hatred of men. Focusing primarily on political activism, these groups have campaigned on issues including a perceived bias against men when custody battles go to court, a belief that men are as much victims of domestic violence as are women, and the need for a greater focus on suicide rates, education levels and deaths in the workplace among men.

Several men’s rights organisations have been working on these issues for decades in Australia. Groups including Fathers4Equality, the Men’s Rights Agency and the Australian Men’s Rights Association have focused primarily on father’s rights, with the Family Court being a core concern. The Australian Men’s Rights Association, for example, argues that an “epidemic” of fatherlessness is hurting children, and has pushed against laws that separate men from their children. They also, somewhat paradoxically, provide men with advice on DNA paternity testing to overcome what they believe is a trend of “paternity fraud.”

Despite their relatively low profile, these groups have had some influence in conservative politics. In 2006 the Howard government amended the Family Law Act to prioritise a child’s right to have access to both parents in the case of divorce. While the legislation offered an exemption in cases of domestic abuse, there is evidence that the shift has resulted in some abusive men having ongoing access to their children.

One of the key advocates for this change was Bettina Arndt, who advised the Howard government on family law and child support issues. Arndt, who was controversially awarded an Order of Australia in 2020, has followed a similar trajectory to many men’s rights activists. Previously a self-proclaimed feminist, she now believes that radical feminism’s critique of men’s behavour has damaged relations between the sexes.

In recent years Arndt has fashioned herself into one of Australia’s leading men’s rights activists. “Now it is men’s lives we aren’t allowed to speak about — the very real problems confronting men and boys in our male-bashing society,” she wrote in her 2018 book, #MenToo. She has become a staple on conservative TV, and frequently appears on Sky News Australia, where men’s rights issues have become a topic of concern.

But other groups have recently taken a higher profile. The Australian Brotherhood of Fathers, or ABF, which has more than 70,000 likes on Facebook, is one of the most active. Its Facebook page discusses the perceived injustices of the family law system and the plight of men denied access to their children.

Mothers of Sons — launched in 2020 at an online forum hosted by the conservative commentator Prue MacSween and featuring NSW One Nation MP Mark Latham — is run by a “group of ordinary women whose sons have faced extraordinary ordeals in our unfair, anti-male legal systems and workplaces.” Mothers of Sons holds to the belief that some women make “false accusations” of sexual assault and domestic violence against men, and rails against the “excesses” of the #MeToo movement.

Like Arndt in the early 2000s, these groups are also achieving some political success, although through different avenues. In recent years men’s rights groups have found favour within Pauline Hanson’s One Nation Party. In 2019, for example, after lobbying by the ABF and members of the “Blokes Advice” Facebook group, Hanson successfully moved for a parliamentary inquiry into the family law system, which is chaired by herself and the former Liberal minister, and high-profile social conservative, Kevin Andrews.

The ABF argues that twenty-one Australian men commit suicide each week following family breakdown, and link this to failures of the family law system. The figure is highly contested, and even former Queensland One Nation leader Steve Dickson, a key men’s rights supporter within One Nation, concedes it is anecdotal. That hasn’t stopped its being taken up more widely by men’s groups.

In pushing for the inquiry, Hanson herself promoted that other, highly contested, belief of the men’s rights movement — that women frequently lie about domestic violence and rape in order to get back at men. “There are people out there who are nothing but liars and who will use that in the court system,” she claimed.

The committee is still at work on its inquiry, but One Nation has already adopted many of the demands of the men’s rights movement as part of its policy platform. The party’s family law policy, for example, takes the view that apprehended violence orders and other court orders shouldn’t necessarily restrict parents’ access to their children, and that allegations of abuse should only be heard during divorce proceedings if they are accompanied by medical records or a criminal conviction.

Although the men’s rights movement has had a growing influence on the conservative side of politics in Australia, Ribeiro and his colleagues found that this older variety of activism is becoming less popular, while groups like the incels and men going their own way are thriving.

Reflecting longstanding assumptions about inherent differences between men and women, men’s and manosphere rights groups often focus on reinforcing traditional ideas of masculinity and femininity. Thus, they believe the gender pay gap reflects women’s inherent desire to spend less time than men in paid work rather than structural problems in the labour force. Using ideas from evolutionary psychology, the manosphere focuses on these supposed differences in sexual and romantic relationships – arguing that women engage in “hypergamy,” a strategy in which they only date men of a higher social, economic or physical status.

The “manosphere” is therefore distinct from the older men’s rights groups in a number of ways. First, its members are less focused on political activism and more on fixing their personal lives. Manosphere discussion primarily focuses on sex and relationships, and features constant complaints about women, sex and love.

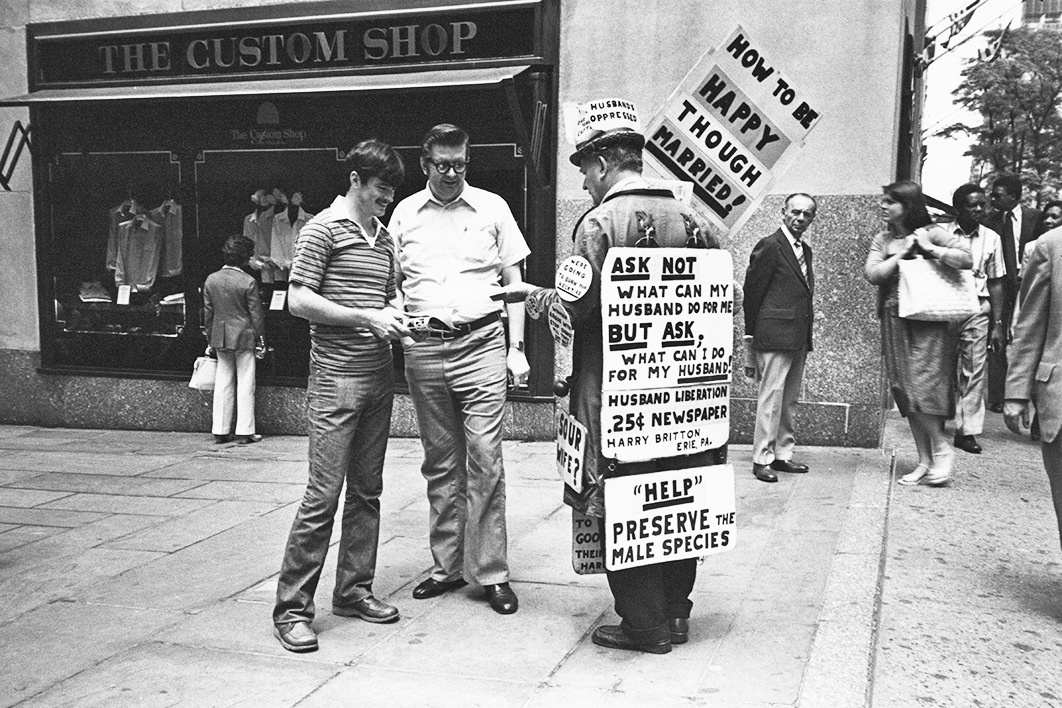

The second major difference between the newer groups and their predecessors is their online focus. Men’s rights activists act in the same way as other established political groups, with men getting together in meeting rooms, in conference halls and, occasionally, on the streets. The manosphere meets most often on Reddit, 4Chan, YouTube, Gab and other social media.

While the influence of the internet in fostering extremism is often overstated, it has had a direct influence on how these groups form and operate. My own research has found that men in these communities have relatively weak connections with each other online. They are attached to the idea of the manosphere but don’t find a deep social connection with others. They often remain deeply socially isolated, sitting at home, online, growing angrier about their lives with no one there to support them.

Other researchers have found that the architecture of social media platforms can push participants towards more toxic and extreme discussion. Research by Tiana Gaudette and colleagues, for example, found that Reddit’s voting function normalised radical anti-Muslim and anti-left sentiment in the forum dedicated to support of Donald Trump. Voting was used to mobilise members around these sentiments, creating the sense that participants are part of an in-group opposed to an identified out-group. Reddit’s upvoting feature produced a “one-sided narrative that serves to reinforce members’ extremist views,” wrote Gaudette and her colleagues, “thereby strengthening bonds between members of the in-group.” My research finds that these sorts of trends are viewable in the manosphere as well.

These new features create a noxious combination. Alongside ongoing social isolation, the belief in essential differences between men and women fosters a form of nihilism in which men see no solution for the problems they are facing. Matched with growing extremist content, this can create an environment of hatred and misogyny, which can push some individuals to undertake deadly attacks.

Australia has yet to see any incel-motivated attacks of the kind experienced in the United States, Canada and Britain. But does that mean the threat doesn’t exist?

The influence of these groups is often harder to measure than traditional men’s rights groups. While many of the online communities are very large, it is impossible to know individuals’ locations or level of commitment.

Some signs suggest that the influence of the manosphere is present in Australia. Prior to the pandemic, influential American manosphere activists frequently made Australia a destination. In 2017, for instance, filmmaker Cassie Jaye visited the country promoting her movie The Red Pill. Taken from the movie The Matrix, the Red Pill is a term used by these groups to describe the process of learning the harsh truths about feminism. Local men’s groups organised screenings of the movie, and Jaye made several high-profile media appearances.

Later, in 2019, Canadian conservative and anti-feminist thinker Jordan Peterson sold out theatres across the country promoting his anti-feminist self-help text 12 Rules for Life. While he is unlikely to see himself as a member of the community, Peterson is famous in the manosphere, particularly for his perceived tendency to “destroy” feminists in interviews or forums.

Similarly, the “seduction industry,” made up of companies and individuals that teach men a range of (often coercive) tactics in order to “pick up” women, has had a presence in Australia for well over a decade. Way back in 2014, Julien Blanc, who has publicly advocated for men to coerce women, had his visa revoked while on a trip to Sydney. Despite this controversy these groups have stayed strong. Early last year the Sydney bookstore Kinokuniya announced a ban on such behaviour when it discovered that pick-up artists were operating on its premises.

The views of these groups are unlikely to represent a significant portion of the Australian population, or even of Australian men. Like the men’s rights movement, the manosphere is relatively small, both globally and in Australia. Yet, with its growth online and its influence in politics, it is a force worth watching. If even one of its members decides to take out his anger in the real world, as happened in Britain just weeks ago, the consequences could be very serious.

Of course, some of the complaints made by these men are well founded. Male suicide rates are extremely high, as are deaths in the workplace. It is also true that men are, at times, the victims of domestic abuse and rape, and as victims are sometimes ignored. Boys often fall behind in our schools, and men face high levels of mental ill-health. These are all issues that need serious attention.

But the ire of the manosphere is directed at feminism rather than the real causes of these problems, and too frequently turns misogynistic. While claiming they stand for gender equality, these groups undermine the serious work needed to achieve it. •