Sometime over the next three months, Sydney’s population will reach five million. If Melbourne keeps growing at its current pace, by 2020 it too will have five million residents – and it won’t stay that size for long.

New figures published by the Bureau of Statistics last week estimate that in just five years to mid 2015, the number of people living in Melbourne grew by more than 10 per cent. That’s like adding the entire population of Canberra and Queanbeyan in just five years.

If our big cities keep growing at the same pace as in the past five years – Melbourne by 2 per cent a year, Sydney by 1.6 per cent – by 2050 Melbourne will have nine million people, and Sydney almost 8.5 million. Even if Melbourne’s growth slowed to something like Sydney’s pace, over the next fifty years both cities would add roughly a million more people per decade.

They’re not alone. In the past decade, Perth has added almost half a million people, although its growth slowed sharply in 2014–15. Brisbane’s growth has been subdued in recent years, but by 2050, on reasonable projections, both cities will be about the size that Melbourne and Sydney are now.

The numbers are kind of breathtaking. Yet they don’t explain what’s really going on, or the consequences for us now – let alone in the future.

Last year roughly half our population growth came from natural increase: that is, births minus deaths. The other half came from net overseas migration: more people settling here than leaving. That might seem a fair balance, but it won’t last. As the population ages, the death rate will rise, and the birth rate won’t. Our natural increase will shrink; immigration will increasingly determine our growth.

Even now, immigration from Asia is the main driver of the nation’s growth – its economic growth as well as its population growth. Both are concentrated where Asian migrants are settling, which is overwhelmingly in Sydney and Melbourne. Perth and Brisbane get a decent share, most other towns with universities are doing well, but the rest of the country is seeing them pass it by.

In the year to last June, the Bureau estimates that 29 per cent of Australia’s population growth went into Melbourne alone: of our net growth of 317,083 people, 91,593 settled in Melbourne. Sydney took 26 per cent of the nation’s growth, and Brisbane and Perth 21 per cent between them. In all, 76 per cent of all Australia’s population growth went into just four cities. It is a safe bet that something like 76 per cent of its economic growth did the same.

Rapid urban growth is not unique to Australia, but in no other Western country are cities growing as fast as ours. It is not unique to our time, but it poses unique challenges.

On the positive side, it helps explain why the Australian economy keeps growing at a pace that looks impressive to Europeans, even if per capita growth is no better here than there. On the negative side, it explains why the roads, trains and buses in those four cities have become so congested, why housing prices have become so inflated – and why the racist underbelly of Australian society refuses to go away.

Net migration overall has been shrinking since 2013, as jobs have become easier to find in Britain and New Zealand, and even Ireland, than here. But the Bureau figures show that it is European and New Zealand immigration that is shrinking – and in the case of Britain and Ireland, reversing – which means our immigration intake is dominated more than ever by Asia.

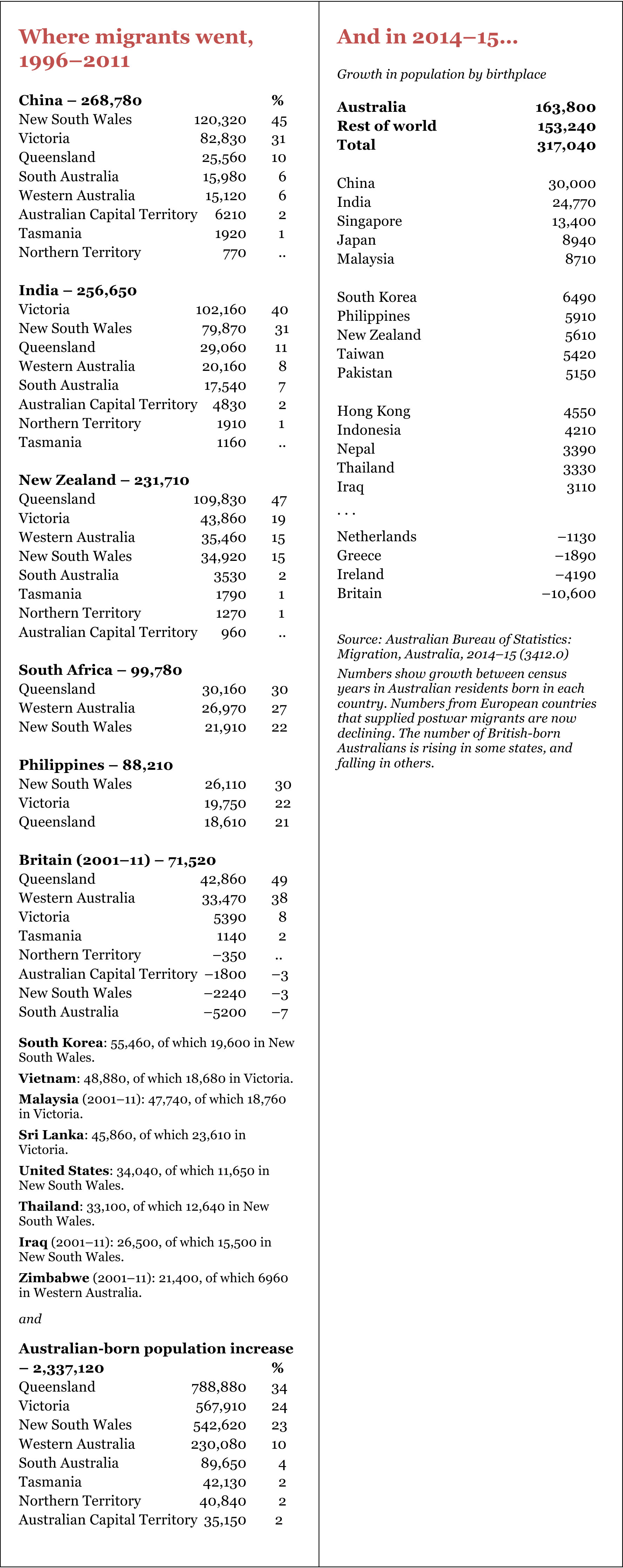

In 2014–15, the Bureau estimates that the number of overseas-born residents grew by 153,240. The number born in Asia grew by 141,960. The European-born population fell, as increasing numbers of postwar migrants breathed their last and thousands of newer arrivals returned to the now-booming Britain and Ireland.

The number of New Zealanders returning home in 2014–15 almost matched the number moving our way; in 2015–16, some forecast that the NZ-born population, too, could fall. Until recently, New Zealand and Britain were two of our four main sources of migrants.

That has implications for national population growth, but even bigger ones for population growth at state and city levels. The Bureau tracks where migrants settle only once every five years, through the census, so its last data is now five years old. But between 1996 and 2011, it estimates that while most of the growth in foreign-born residents was in New South Wales and Victoria (that is, Sydney and Melbourne), migrants from white English-speaking countries settled mostly in Queensland and Western Australia.

Between 1996 and 2011, the Bureau estimates that New South Wales and Victoria absorbed three-quarters of the growth of residents born in China, and almost the same share of migrants from India. Nearly all that growth was in Sydney and Melbourne. In New South Wales, only 5 per cent of Chinese residents lived outside Sydney, and just 8 per cent of Indians. In Victoria, even fewer Indians or Chinese settled outside Melbourne.

White English-speaking migrants followed a very different pattern. Between 2001 and 2011, 49 per cent of the net growth in British-born residents was in Queensland, and 38 per cent in Western Australia. The number of British migrants living in New South Wales actually declined, and in Victoria it grew only marginally.

There’s an urban myth that New Zealand migrants concentrate in Sydney. Not so: between 1996 and 2011, 47 per cent of the net growth in their numbers was in Queensland. Even Western Australia attracted more New Zealanders than New South Wales. Brisbane is the real Kiwi capital in Australia, and the rest of Queensland put together has more of them than Sydney.

Likewise, in net terms, 57 per cent of South African migrants settled in Queensland and Western Australia. Their numbers have also fallen off sharply. In 2014–15, in net terms, 93 per cent of our growth in foreign-born residents came from Asia.

There has been a marked change, too, in where they’re coming from. While China (30,000) and India (24,770) are clearly the biggest sources of migrants to Australia, in 2014–15 the five new rich countries of Asia contributed 38,800 between them, more than either of Asia’s two giants.

Singapore suddenly jumped to third place in our migration numbers, followed by Japan (fifth), South Korea (sixth), Taiwan (ninth) and Hong Kong (eleventh). Add middle-income Malaysia (fourth) and there’s clearly a new dynamic in our immigration intake. How many of these newcomers will remain in Australia, and how many are just here to study or get overseas experience before going back home remains to be seen.

What is clear is what it means for our future urban growth. With some exceptions – Western Australia gets an outsize share of migrants from Southeast Asia, and many Filipinos and Japanese settle in Queensland – Asian migrants overwhelmingly make their homes in Sydney and Melbourne. Between 1996 and 2011, Sydney was the top destination for migrants from China, the Philippines, South Korea and Indonesia. Melbourne was the top choice for those from India, Malaysia, Singapore, Vietnam and Sri Lanka.

Sydney and Melbourne have long housed roughly 40 per cent of Australia’s population, and gained slightly more than that share of population growth. But last year, the dominance of Asian migrants saw them take 55 per cent of the nation’s population growth in 2014–15 – and probably an even higher share of growth in economic activity.

Not only did Melbourne grow by more than any other city, but it also grew faster than any of the other top twenty cities, something that probably last happened in 1852. The rest of Victoria added fewer than 8000 people, with almost half of that in Geelong – now a virtual satellite city of Melbourne, growing as fast as the Gold Coast.

Sydney, too, grew faster than Perth or Brisbane, faster than any of the larger towns in Queensland except the Gold Coast. But one has to question whether growth at this pace makes Melbourne or Sydney better places to live, when their governments are unwilling to invest in infrastructure on a scale needed to match their growth.

Since the start of this millennium, Melbourne’s population has grown by a third, Sydney’s by a quarter. But Melbourne does not have a third more road space to carry its cars and trucks, or a third more trains and trainlines, or schools, or a third more of the other infrastructure that makes cities liveable.

The legacies of the past gave governments some scope to put all that off for a while. But that freedom should have given way long ago to a sense of responsibility, and a recognition of the need to meet the growth in population. State Treasuries have been short-sighted, inflexible and irresponsible in advising their governments not to invest on the scale required, lest it cost them their AAA credit rating. What we lose in paying marginally more for our loans is dwarfed by the widespread loss of time, amenity and money as our overstretched urban services deteriorate for lack of investment, and even adequate maintenance.

Regional Australia in 2014–15 showed no benefits from a Coalition government. In all states except New South Wales and Queensland, more than 90 per cent of population growth was in the capital city. The regional centres that have done well in recent years are mostly those with universities, which can attract a share of our biggest export industry (far bigger than coal or iron ore) – education.

It’s worth making a mental note of these trends. As long as our growth is driven by economic migrants and students, they are likely to continue. Australia’s population will keep growing at the fastest pace of the larger developed countries. And without changes to policy, that growth will pour primarily into four cities.

There are issues we should think about here. All things considered, would it be in the public interest to have a more even spread of population growth? Should governments intervene to try to achieve this? If so, how? It’s a big ask in a political culture that has become accustomed to thinking of government intervention in the economy to achieve social ends as at best counterproductive and at worst corrupt.

Failing such moves, we need to see political courage from our leaders to tackle the infrastructure backlogs that are growing with each year. If we want tax reform, isn’t it time we had a congestion tax to ration overcrowded urban road space, accompanied by higher public transport fares so that users at least pay half the cost of the service they benefit from? That could raise billions of dollars over time, which could be ploughed into investment in better road and rail services, such as metro systems in Sydney and Melbourne.

At current growth rates, Melbourne and Sydney will be adding a million people a decade over the next half-century. Their ethnic composition will change dramatically; it probably won’t change the culture much – second generations of whatever ethnicity tend to be Australians first – but it will in some ways. And the urban liveability on which we pride ourselves will keep eroding, so long as our governments dodge the challenges of being a high-immigration society. •