May 2016 will be remembered as a watershed for the Republic of Austria. Within a single week, the central European country got a new chancellor and elected a new president. A country ruled almost continuously since the end of the second world war by a coalition of the same political parties is being buffeted by unaccustomed winds of change.

Austria’s new president, seventy-two-year-old Alexander Van der Bellen, is a retired professor of economics who led the Austrian Greens between 1997 and 2008. He is the first president since 1945 not to be nominated by either of the ruling parties, the left-of-centre Social Democrats or the conservative People’s Party.

In last Sunday’s election – a run-off after an indecisive first round on 24 April – Van der Bellen beat his forty-five-year-old rival, Norbert Hofer of the far-right Freedom Party, by a paper-thin margin of about 31,000 votes. Austria came close to electing a populist, right-wing, Eurosceptic president.

The election was preceded by a campaign that sometimes seemed entirely devoid of substance and lacking in any sense of political standards. Televised debates regularly degenerated into political mud-slinging. After a particularly ferocious debate, a public commentator bitterly summed up: “Both [candidates] disgraced, presidency damaged – discussion was at a kindergarten level.”

By the end of the campaign, a visibly exhausted Van der Bellen managed to convince a slight majority that he had a better understanding of the role of the president, whose main task, in practice, is to represent Austria externally. He successfully painted a scenario in which Hofer, having been elected president, would receive congratulations and support only from Europe’s far right. He convinced a shade more than 50 per cent of the Austrian population that a far-right president would damage Austria’s reputation in the world.

That argument would have resonated particularly with voters who remembered the embarrassment occasioned by the presidency of Kurt Waldheim (1986–92), who was declared persona non grata by the United States after he was found to be implicated in war crimes. And, indeed, a broad wave of relief went through political circles and the world media after Van der Bellen’s victory. “That is a weight off Europe’s mind,” said Germany’s foreign minister, Frank-Walter Steinmeier.

During the campaign, both candidates drew attention to the power and role of Austria’s highest-ranking official. Besides the core tasks of representing the republic externally and swearing in the government, the president’s role was extended by a constitutional amendment of 1929. Theoretically, he or she is authorised to dismiss the government, remove individual members of a government, and even dissolve the parliament as a whole.

All presidents of Austria’s post-1945 Second Republic, however, have executed their office with sensitivity and reluctance. On only one occasion, in 1999, has a president intervened in a government-building process by refusing to swear in particular ministers. During the recent election campaign, Norbert Hofer repeatedly mentioned that he would dissolve a government that did not “follow his ideas of how a state should be ruled.” Van der Bellen, for his part, said on several occasions that he would refuse to swear in a government led by the Freedom Party leader, Heinz-Christian Strache.

The Austrian president might be entitled to act in this way, but the strict division of powers between president and parliament wouldn’t have given either man free rein. Parliament always has the last word, and the federal assembly, consisting of members of both chambers of the parliament, can dismiss the president and put an end to a presidency that exceeds its powers.

Presidential election results have never been closer than this in Austria. Van der Bellen gained 50.35 per cent, thereby more than doubling his vote in the first-round ballot in April. The other 49.65 per cent of electors voted for Hofer, who had focused on domestic issues, tried to draw on patriotic, if not nationalistic, sentiments, and made much of the current government’s handling of the 2015 refugee crisis.

One of the most important points of friction between the two candidates was their different attitude towards the 90,000 people who sought asylum in Austria in 2015 and towards the governmental responses to the refugee crisis. Van der Bellen, the son of Eastern European immigrants, advocates a policy of open borders and described the refugee influx as “a chance to integrate young and intelligent workers.” Hofer, on the other hand, has always opposed immigration and was one of the authors of the Freedom Party manifesto, which is widely regarded as xenophobic.

The result of the elections was evidence of a deep split within the Austrian population. City dwellers tended to support Van der Bellen; rural Austria predominantly voted for Hofer. There was also a significant gender gap: the firearm enthusiast Hofer gained more support from men; the liberal environmentalist Van der Bellen managed to convince 60 per cent of Austria’s female voters to support him.

Viewed according to profession and level of education, the split becomes even more striking. An overwhelming majority of blue-collar voters (86 per cent) supported the Freedom Party candidate, while white-collar voters largely supported Van der Bellen. The former economics professor also received broad support from tertiary-educated voters (81 per cent), while 67 per cent of voters who have completed an apprenticeship opted for Norbert Hofer.

What is happening in Austria? What explains the close result and the widespread support for Hofer?

For more than seven decades, this central European country has been ruled by a coalition government of its two largest political parties, the Social Democrats and the People’s Party. In the years immediately after the second world war, both parties had to find ways of overcoming the violent prewar differences that had erupted into a fierce civil war. They established a form of collaboration that later became known as consensual politics. In order to keep both partners satisfied, coalition governments sought to avoid disputes as much as possible. Austrian politicians became masters of compromise: every concession had to be bought by further concessions.

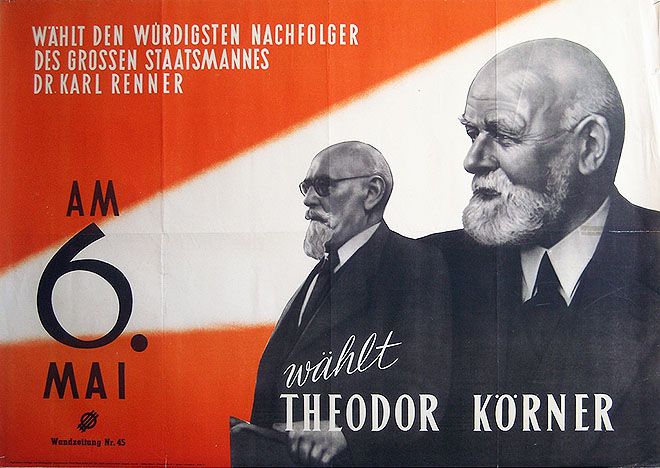

The Social Democratic Party’s Theodor Körner (right) became Austria’s first popularly elected president in 1951 after the death of Karl Renner (left). Marleen Zachte/Flickr

In the process, both parties became increasingly alienated from their voters, and their consensual style prevented them from carrying out necessary structural reforms. The nation’s agenda was buried in endless committees, political jockeying and meaningless rhetoric. Over the past two decades, political dissatisfaction grew among large parts of the Austrian population, and the support for both parties in state elections declined rapidly.

The annihilating results for the presidential candidates for both the People’s Party (11 per cent) and the Social Democrats (11 per cent) in the first round of the presidential elections on 24 April led to much soul-searching. On 17 May, the Social Democrats replaced the former chancellor (Austria’s equivalent of a prime minister), Werner Faymann, with Christian Kern, a businessman without any significant political experience. In his inaugural speech, Kern gave a damning verdict about the politics of his predecessors. “The meaninglessness of the past decades will be my driving force,” he said, adding, “If we continue to enact this drama, the drama of power obsession and forgetfulness of the future, then we only have a few months until the final impact. A few months until the people’s trust and support are fully used up.” Referring to US president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Depression-era initiative, he proposed a “New Deal” to overhaul Austria’s moribund state structures.

It is also important to remember that large sections of the Austrian population did not receive civic education in school. Politics was only introduced into Austrian schools as a subject a few years ago, and still doesn’t play an important role in school curricula. Consequently, many Austrians don’t know a great deal about political institutions, political decision-making, or – as we saw during the election campaign – the role of the president.

The past seven years have brought unprecedented challenges for the Austrian government. As a result of the lack of reform, unemployment rates are at an all-time high, economic growth is lagging behind the European average, businesses, entrepreneurs and scientists are leaving the country, and Austria’s universities are falling back in rankings. Billions of euros were lost in the self-inflicted fall of a major state-owned bank during the global financial crisis, and the refugee crisis has brought more than a million people through Austria since 2015, highlighting the government’s indecisiveness.

For decades, the governing coalition has been unwilling and unable to lead a discussion about integration and immigration. The Freedom Party was able to “own” these issues, exploiting them to create fear among the population. After their poll results deteriorated rapidly at the end of 2015, the Social Democrats and the People’s Party abruptly introduced a tough new policy of closed borders that contrasted starkly with their previous approach. Many commentators observed that the government, by trying to outflank the hardline Freedom Party, had lost its last shred of credibility along with its reputation abroad. In fact, the refugee crisis could be seen as the final catalyst for change in Austria, and the factor most responsible for the outcome of the presidential elections.

Is Austria drifting towards the far right? It may seem so. But what we are seeing should instead be regarded as a radical expression of a highly dissatisfied population, many of whom wouldn’t necessarily associate themselves ideologically with the Freedom Party. They wanted to express their discontent at an election that traditionally has not been given a high priority by many Austrians (there have even been debates about abolishing the presidency). Here again, part of the problem is the neglect of politics as a subject of study in schools.

Losing votes is nothing new for the People’s Party and the Social Democrats. In fact, Austria’s ruling political elite has been losing votes for more than two decades. The last national elections in 2013 allowed them to continue their coalition only with a wafer-thin majority of 50.81 per cent. The recent presidential elections and the high percentage of votes for Norbert Hofer must be seen in that context. The striking political dissatisfaction became visible during the first ballot, when the relatively unknown, liberal independent candidate Irmgard Griss managed to gain almost as many votes as the candidates of both ruling parties combined – without any party support.

Recent events reveal that Austria’s ruling elites have recognised the problem. The two highest positions in the country are now occupied by a president who doesn’t belong to either the Social Democrats or the People’s Party leadership, and a chancellor who – after strongly criticising the politics of his predecessors – proposes a New Deal for the country. Great challenges await both of them. •