The advent of autochrome in 1907 was something of a sensation among the fast-expanding world of photographers, amateur and professional. Invented by the pioneers of cinema, the Lumière brothers, it marked the first time that a method for producing photographic images in colour — in this case by means of painstakingly prepared, single-use glass plates — became both commercially available and commercially viable.

It didn’t come as a surprise. The previous fifty or more years had seen many attempts to produce colour images. Some had achieved encouraging if fleeting results, but the images either could not be fixed, or survived only for a brief time.

By the early twentieth century, progress was such that a good many rivals were competing to come up with a process that was accessible, relatively affordable, and able to represent the world as it is — in colour. The Lumière brothers won that race. Autochrome was, in the words of the influential photographer and critic Alfred Stieglitz, “a dream come true,” a marvel of modern technology.

Thanks partly to the unrestrained enthusiasm of early-day influencers like Stieglitz, autochrome was an immediate success. Photographers with sufficient means were keen to try the new system. It was felt that, in some profound sense, the capacity to produce images in colour would unequivocally establish photography as no longer an ambitious interloper but an art form in its own right, one that would stand on equal terms with its elders.

For J.M. Bowles, who wrote extensively on art and photography, “the modern photographic print needs colour in order to make it a complete work of art.” The need had long been identified; now at last it was being met. For many of the self-styled Pictorialists, for example — those photographers who took an avowedly painterly approach to their work with the camera — colour offered the means to justify their claims for photography’s status.

In the October 1907 edition of his journal Camera Work, Stieglitz was unreserved in his vision of the future. Not only would the practice of colour photography become widespread, it would also provide new creative opportunities for those with the necessary talent to take full advantage of its potential. “The photographer who is an artist and who has a conception of colour will know how to make use of it.”

Not every photography enthusiast felt this way. The critic and editor Dixon Scott, for example, lamented that the “lilliputian Frankensteins” — a reference to the tiny, coloured dots, made from potato starch, that coated the plate and formed the bedrock of the colour image — would render it “impossible for the human hand to interfere.” The dots would make the photograph on their own, limiting the ability of the photographer to manipulate the image to create effects of the kind that could be achieved with monochrome. For this reason, Scott declared, photography’s “true sphere must always be the world of monochrome.”

From excited to despondent, these differing reactions were united in the certainty that the invention of the autochrome image heralded a revolution. It just wasn’t clear where the revolution was headed. Whether the new world of photographic colour would turn out to be a good thing or a bad thing remained to be revealed.

As Catlin Langford shows in her fascinating account of the rise and fall of autochrome, Colour Mania, the enthusiasts initially triumphed over the doubters. Drawing on the V&A’s considerable collection of some 2500 autochromes, and aided by excellent reproductions, Langford shows how the best of these early colour images, with their characteristic combination of realism and other-worldliness, “are as alluring today as when the process was first made available.”

In 1907, the future of colour photography seemed assured. Processes would inevitably improve, and before long colour rather than black-and-white would become the dominant medium. And yet it did not quite happen that way. Within only a few years some of the most prominent of the initial enthusiasts, including Stieglitz, had largely abandoned the new method for the more familiar and more flexible “world of monochrome.”

The portraitist and fashion photographer Adolph de Meyer, who declared in 1908 that he “no longer had an interest in monochrome photography,” returned to black-and-white a mere two years later. Although he was initially excited by colour’s possibilities, that excitement waned after a brief period of experiment. For de Meyer, monochrome continued to be where the real technical and artistic possibilities lay.

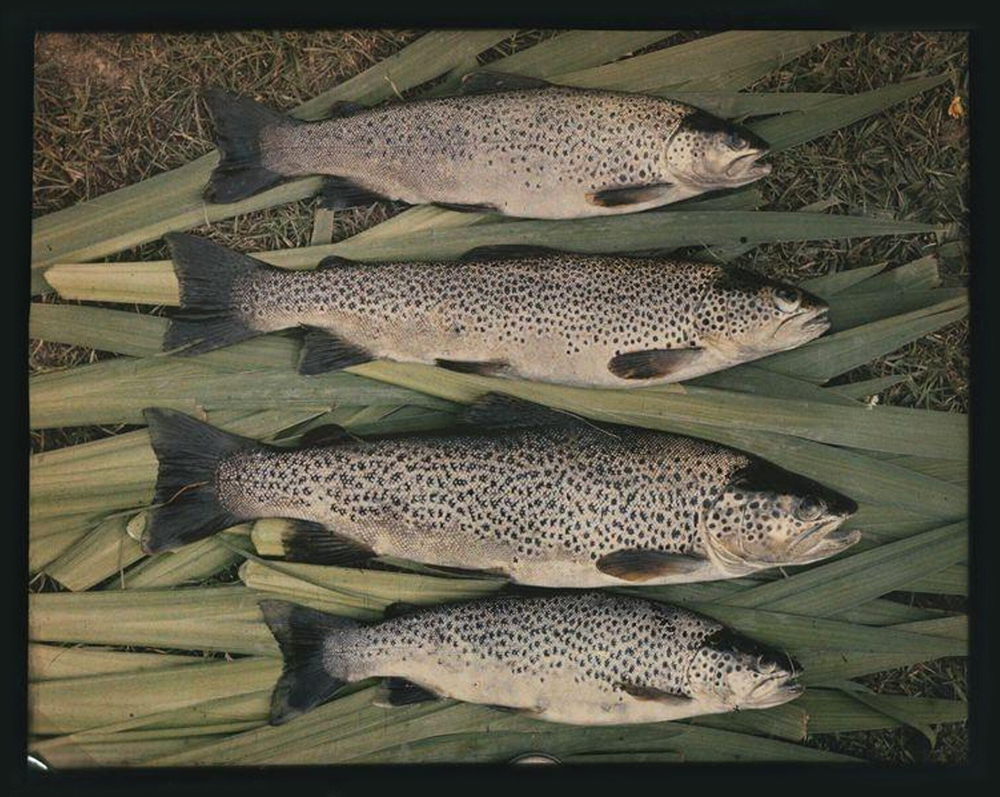

Adolph de Meyer’s Four Trout (1909). Victoria and Albert Museum

And yet de Meyer’s experiments with colour in those two years captured much of the promise and potential of autochrome. Langford includes half a dozen of de Meyer’s works in Colour Mania, all from the period 1908–09, all of them still lifes in which he explores the impact of various colour combinations. In one particularly effective example, Four Trout (1909), the fish of the title are arranged in a vertical row, one above the other, on a similarly arranged bed of waterweed.

Because of its highly patterned nature, this exercise in geometrical composition could also be extremely effective in monochrome. Indeed, the stippled trout look at first glance almost to be in black-and-white. It is the pale green of the background leaves that provides the dominant colour, causing the eye to focus as much on the backdrop as on the fish of the title. Four Trout is a fascinating exploration of colour’s ability to make a difference to how we see, yet it was an exploration that de Meyer felt he could take only so far.

In retrospect, it is not surprising that the initial enthusiasm for autochrome faded away. Autochromes took photography backwards as well as forwards. While improvements in monochrome cameras and associated processes had made it easier to travel light and respond more readily, autochrome revived more complex methods of preparation and display, and set back progress towards the highly desirable goal of capturing the moment.

Monochrome photography in the early twentieth century was rapidly being democratised. By contrast, the new colour process recalled a time when the practice of photography required considerable money and time and was an occupation for the few. The relatively cumbersome business of making a colour image seemed to belong to the past almost as much as to the future. Not only was making an autochrome demanding, but the result was uncertain and fragile.

In a detailed account of the process itself, Langford points out that while no specialist equipment was required — “any plate camera could be used” — the business of preparing and developing the plate involved many steps and left considerable room for error along the way.

Long exposure times, sometimes of a few seconds and often much longer, were required, obliging the photographer to minimise movement of the subject. Flowers, for example, were often brought inside to avoid any hint of wind that might ruffle the petals. After all this effort, an autochrome was difficult to reproduce effectively on paper. It needed to be backlit for display, and then for only short periods lest the plate be damaged and the image ruined.

Autochromes had their own mortality built into them. Langford quotes an estimate that fifty million autochromes were created during the twenty-five years in which the plates were commercially produced. Few have survived. Yet to view an autochrome in those early days, briefly backlit in a darkened room, must have been a thrillingly theatrical experience.

As more and more professional photographers returned to favouring monochrome, an opening was left for the supposedly less talented, “these people with their silly little enthusiasm and their inability to appreciate the niceties of colour,” as the photographic portraitist Alvin Langdon Coburn unkindly put it. The French Pictorialist Robert Demachy meanwhile resigned himself “to the inevitable atrocities that the over-confident amateur is going to thrust upon us.”

Yet for those who stayed the course of colour, gifted and persistent amateurs with the necessary means, it was also an opportunity for a further blurring of the distinction between professional and amateur, a blurring that had always existed and has never really gone away.

It is one of the most fascinating aspects of the history of photography in the twentieth century that colour, from its first commercial appearance in 1907, did not sweep the board, at least as far as art or what might be called serious photography was concerned. With major exceptions, particularly in areas such as fashion and travel photography, black-and-white retained its artistic dominance for many decades.

This was not only because of the difficulties, complexities and cost of making autochromes, nor of the challenges in producing an easily viewable image. It was also because the effect of colour, while immediate and striking, was felt by many to be ultimately unsatisfying, the equivalent of popular fiction. Monochrome was more literary.

The introduction of Kodachrome in 1936, which would help make colour photography both simpler and more affordable, reinforced this effect. Colour went on to become the medium for recording family occasions and holiday outings rather than the preferred medium for artistic expression. It was not until the 1970s, with the rise of photographers such as William Eggleston and Joel Meyerowitz, that colour photography finally began to be recognised and appreciated for its full artistic capabilities.

Colour now dominates our view of photography. To many eyes, images in greyscale, which speak of the past, need colour to become truly alive. Hence the boom in colourising, by which the dead past is reanimated for contemporary eyes. The digital artist Marina Amaral, for example, has built a huge following by colouring black-and-white photographs, thereby “breathing life into the past.”

Amaral’s most recent book of colourised images, A Woman’s World 1850–1960, co-authored with historian Dan Jones, follows two highly successful earlier volumes in which Amaral and Jones focused on colourised images of key historical events and of war. A Woman’s World is described as offering “a strikingly fresh perspective on the female experience during an era of extraordinary events,” by which “these women and their lives are brought wholly to life.”

Autochrome, seen in this context, was a false start. It offered the means of bringing the world “wholly to life,” but it was not until half a century later that colour was kickstarted onto its path to dominance. Colour Mania takes us back to the beginning, providing an opportunity to assess the achievements of these early experimenters with colour, and to understand why they did not lead at once to the revolutionary change that many expected.

Making and then viewing an autochrome entailed a good deal of effort. Autochromes were advertised as rendering photography “true to life,” but arriving at that truth required considerable creative deception. Autochrome recorded the artificially static, not life as it was lived. Spontaneity was out of the question. Langford records the advice of one contributor to the British Journal of Photography: “rose trees that are rather bare may have a few blooms wired on for the occasion.”

Photographers were obliged to take particular care in selecting their subjects, avoiding overly sharp contrasts and incompatible colours (which could cause a “fried egg effect,” rendering the centre of the photo darker) and instead favouring certain colours, for example red, which reproduced particularly well and contributed to a striking yet harmonious whole. The ability of red to anchor the image can be seen in Mervyn O’Gorman’s dramatic and justly famous portraits, from 1913, of Christina, dressed in red and photographed against a coastal background.

Of the photographers represented in Colour Mania, the one to best show the full potential of autochrome was the one who stayed loyal the longest. F.A. (Friedrich Adolf) Paneth was a quite remarkable man. His day job, so to speak, was as a chemist, a field in which he achieved great distinction. On leaving Germany with his family in reaction to the rise of Hitler, he worked principally in Britain and America before capping a brilliant career as director of the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz.

Paneth brought the same intelligence, inventiveness and precise eye for detail to his hobby of photography as he did to his profession of chemistry. Rather than being frustrated by the constraints of the autochrome process, he seemed to relish the challenge of working with them to maximum effect. Langford describes how Paneth even stockpiled a supply of autochrome plates to use against the inevitable day when production would cease. When that day came, in 1932, he continued to produce autochromes until, reluctantly, he switched to newer technologies. It seems that even then he would sometimes process his images in ways that would cause them to resemble autochromes.

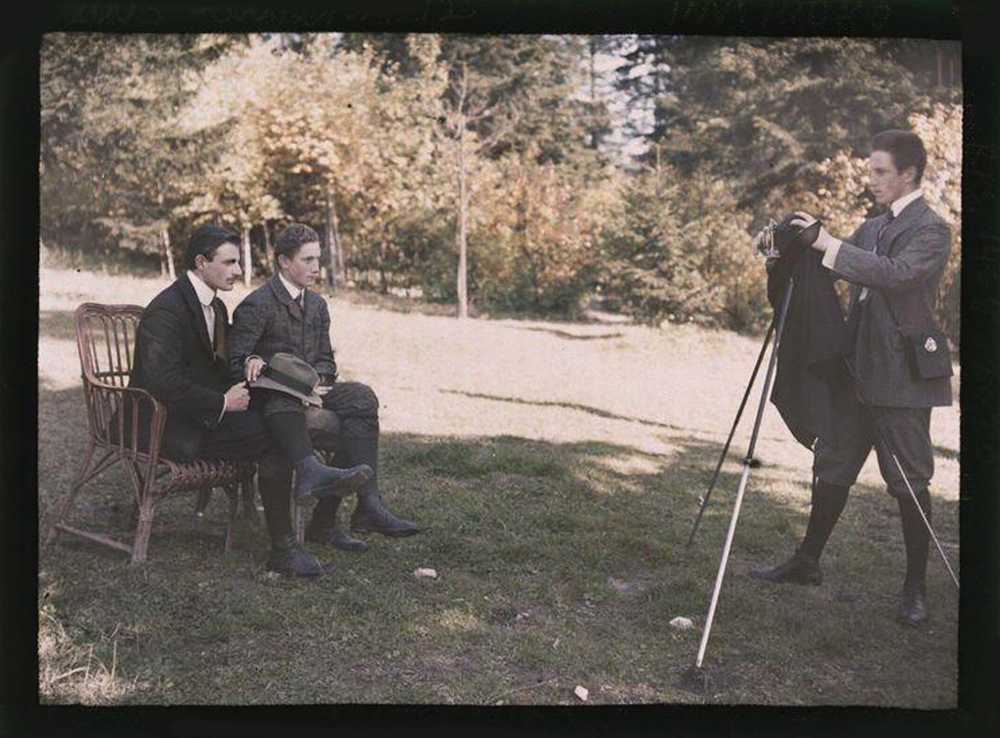

A.F. Paneth’s Lutz, Otto, and Myself at Semmering, Austria (1908). Victoria and Albert Museum

As Langford rightly notes, Paneth’s scientific mind and methodical approach, though they resulted in highly composed images, “nevertheless convey a sense of immediacy” and of “intimacy.” This is particularly noticeable in his group photographs — of friends, family, colleagues and students.

It is difficult for any photographer to capture in such an image a genuine sense of equality and companionship. Certain faces or figures will tend to dominate and demand particular attention. Paneth, however, had a talent for distributing our attention equally across the figures in the frame.

In one striking image, Lutz, Otto and Myself at Semmering, Austria (1908), Paneth is shown photographing his brother and their friend Otto. The men are formally dressed in the manner of the time, and rather stiffly posed. Yet the image relays an impression of mutual affection and of collaboration in this new way of making images, an impression reinforced by the vitality of colour. Paneth, whose work was never exhibited in his lifetime, was both a conservative — he stuck to his last — and an innovator, pointing the way ahead, never losing his faith in the bright future of colour. •

Colour Mania: Photographing the World in Autochrome

By Catlin Langford | Thames and Hudson | $90 | 238 pages