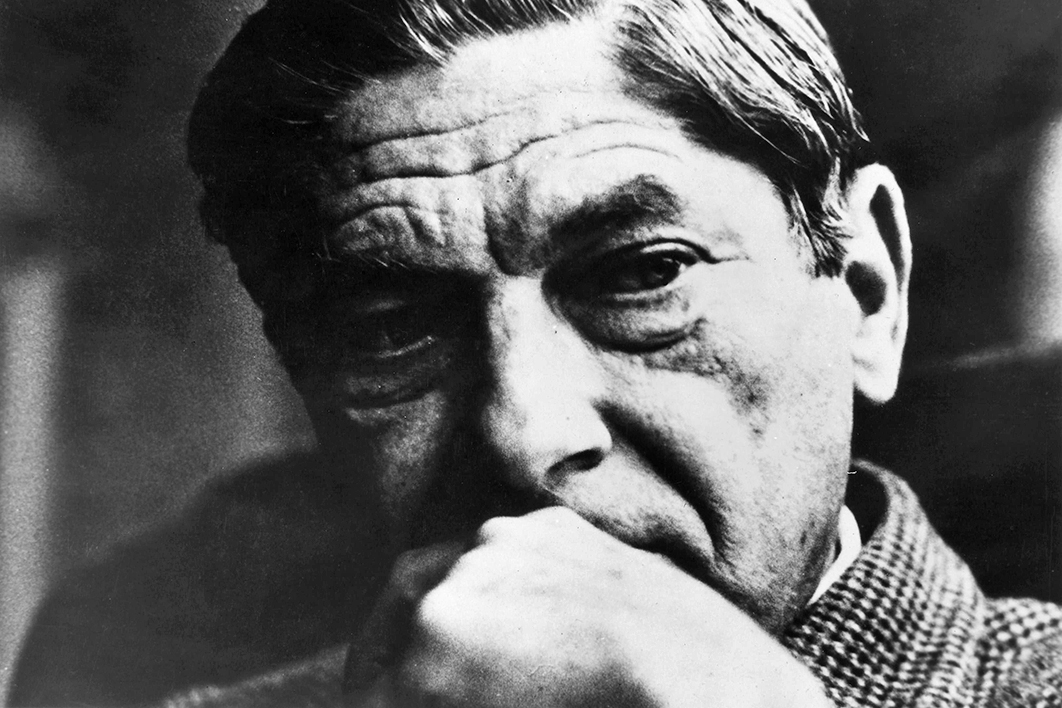

Watching Professor Robert Manne on a recent episode of the ABC interview series One Plus One, I began to reflect on a class I took with him during my undergraduate degree. Since then, the ideas he introduced have taken on increasing importance in the light of current global trends and how they are manifesting in Australia. Domestic political debates are producing an increased suspicion of our core liberal-democratic institutions — parliament, the courts, universities, the media — and this has the potential to hamper both our internal stability, and our wider strategic capabilities.

Each week’s discussion in Manne’s class revolved around a key essay or book that illuminated the events and ideas that shaped the West during the twentieth century. The framework was laid out by Eric Hobsbawm’s Age of Extremes, an intricate account of the dramatic upheavals during what he called “The Short Twentieth Century, 1914–1991.” By extremes, the historian was referring not just to the violent brutality of that era but also to the great prosperity that emerged in sections of the West following the second world war.

The forces driving the violence were identified by George Orwell in his essay “Notes on Nationalism.” Written towards the end of the war, it bears witness to the destructive effects of conformist mass movements. Orwell used the term “nationalism” in a broad sense to indicate any in-group partiality, whether to a particular ethnicity, a nation state, a political party, a religion, or an ideological orthodoxy. His concern was with “the habit of identifying oneself with a single nation or other unit, placing it beyond good and evil, and recognising no other duty than that of advancing its interests” and with the “self-deception” that underlies that drive.

Anticipating the tendency of today’s social media, Orwell wrote that “the smallest slur upon his own unit, or any implied praise for a rival organisation, fills him” — the nationalist, male or female — “with uneasiness which he can only relieve by making some sharp retort.” Transcending that impulse is difficult: humans are inclined towards group identity, and in periods of significant change our parochialism becomes more pronounced as we seek the security of the familiar. The pluralist liberal democracies that emerged in the West in the period after the second world war were remarkably successful in overcoming, or at least subduing, those potentially self-destructive impulses.

Francis Fukuyama’s essay-turned-book The End of History? explained how this inclusive form of liberal democracy consolidated itself in the West and provided the setting for a considerable increase in social stability, prosperity and individual flourishing. But the essay was not the work of Western triumphalism that both its admirers and detractors believed it to be, and its closing chapters presciently anticipated the rise of destabilising figures like Donald Trump. If liberalism’s core tenets of universal access and opportunity were neglected, Fukuyama observed, then it would become vulnerable to figures keen to exploit the loss of confidence in its core values among those who feel their needs are being neglected.

The return to prominence of illiberal figures is both a symptom and a cause of the current age of uncertainty. How we treat the institutions that hold these figures accountable will indicate whether we see the dangers of overreach by government as a primary lesson of the twentieth century — a lesson conservative parties did embrace in the postwar period — or whether the temptations of state power to consolidate in-group ascendency re-emerge.

While another of our readings, Friedrich Hayek’s Road to Serfdom, may have taken an almost absolutist position on state power, his argument that the desire to control trade is an authoritarian instinct should be recognised and the tendency resisted. Hayek asserted that the state lacks the intimate information to understand how companies best produce their wares, which makes the desire to control how they operate misguided at best and nefarious at worst. That desire also demonstrates a disdain for the international institutions that allowed the West to flourish after the second world war.

Liberalism’s trust of human interaction (with prudence), and authoritarianism’s compulsive distrust formed the overarching theme of Robert Manne’s classes. Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man provided us with a harrowing first-person account of his existence inside a Nazi concentration camp. From his prison cell, Czech dissident Václav Havel dissected the nature of totalitarian regimes and their incessant need for conformity in The Power of the Powerless. Arthur Koestler’s novel Darkness at Noon explored similar themes of submission to a state that creates its own truth. And Sven Lindqvist searched for the roots of this dehumanisation in Exterminate All the Brutes.

Self-reflection of this kind is not a form of self-loathing but a vital component of a society’s self-preservation. The success of liberal democracy derives from an appreciation of and respect for the core civic institutions vital to its maintenance. Institutions that provide high-quality public information and those that help develop the skills to critically assess information and mitigate instinctive biases are fundamental to the prevention of democratic backsliding. University classes like Manne’s help create an awareness of how and when the seeds of discordance return.

The erosion of public trust in the institutions that serve as the structural defenders of liberal democracy is also a major threat to Australia’s strategic interests. Unlike the United States, Australia doesn’t have the capacity to maintain a high level of international influence if its internal institutions are destabilised. Here, the undermining of core institutions provides opportunities for strategic competitors to insert themselves into abandoned spaces. In a shifting global order, with Australia’s relative regional power set to decline, protecting core institutions — those that have allowed the country to become highly stable and prosperous, and punch above its weight — is paramount.

That the culture of suspicion towards these essential liberal-democratic institutions is originating from conservative figures demonstrates how increasingly untethered Australian conservatives have become from a philosophical conservatism for which the defence of institutions has always been a primary goal. Theirs has become the nationalism — in Orwell’s sense — that is undermining the national interest. In order to maintain Australia’s domestic resilience it would be wise for them to carefully consider the wider implications of the political tactics they use. Maybe they should take a class?