Joe Biden may not think much of Scott Morrison’s approach to climate change, but when he gets round to appointing a new ambassador to Australia it’s unlikely the mission statement will be as hostile as the one Richard Nixon gave Marshall Green in February 1973. Nixon was sending that unusually senior foreign policy figure to sort out Australian prime minister Gough Whitlam.

“Normally, Marshall, I wouldn’t send you to a place like Australia, but right now it is critically important,” Nixon told him, as recounted in James Curran’s book Unholy Fury: Whitlam and Nixon at War. Then followed a string of presidential expletives about Whitlam. “Marshall, I just can’t stand that c—t.”

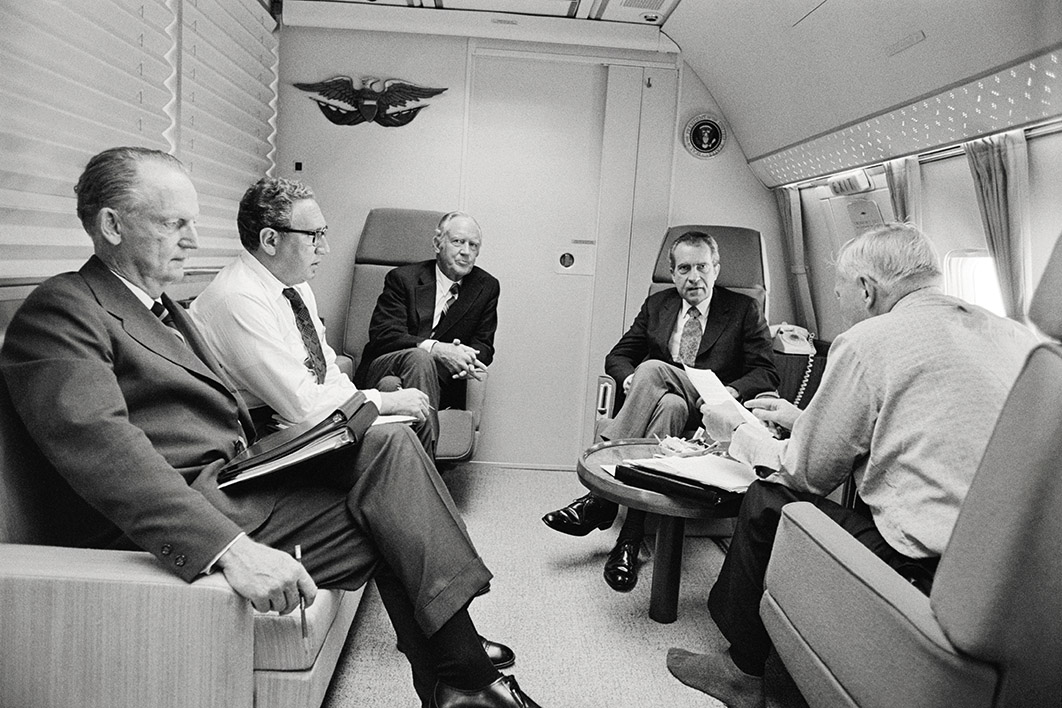

By most accounts, Green is the heaviest Washington hitter ever appointed to Canberra. Originally a Japan specialist — as secretary to ambassador Joseph Grew in Tokyo before Pearl Harbor and then in wartime intelligence — he moved to the State Department, where he headed missions around Asia before becoming assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific Affairs. In that capacity, he accompanied Nixon to his historic meeting with Mao Zedong in 1972.

“He was regarded as ‘Mr Asia’ at a time when [Henry] Kissinger’s expertise on the region was regarded as relatively thin, and indeed there is some speculation that Kissinger wanted him out of Washington for that very reason,” says Curran, a professor of modern history at the University of Sydney who closely studies the US relationship. “Green had the capacity to show him up.”

For this reason Green’s appointment was widely welcomed. “Even the Labor people were saying ‘we got Marshall Green,’ as if to underline that DC was at last taking Australia seriously,” says Curran.

In reality, Canberra got Green because several members of Whitlam’s government had seriously irritated Nixon by condemning the bombing of North Vietnam, which was designed to force concessions at the Paris peace talks. Whitlam’s people might have noted that Green’s postings tended to precede attempts to overthrow the host government — successfully, in the case of general Park Chung-hee in Seoul in 1960, and as a pretext for a crackdown by General Suharto’s group in Jakarta in 1965.

Concerns that Whitlam might blow the cover of the Pine Gap satellite spy station or even close it down were part of the drama around the 1975 dismissal of his government, but Curran found that Green had already helped soften the animosity between the two leaders.

“It was Green, along with Peter Wilenski in Whitlam’s office, who fixed the embarrassing problem where Whitlam had been frozen out of getting a White House meeting with Nixon,” Curran tells me. “By the end of his posting Green was pouring a whole lot of cold water on the ‘all the way’ mentality and rhetoric, saying that Washington now agreed with Whitlam’s call for a ‘new maturity’ in the relationship. Doesn’t that seem another world!”

Green is thus often seen as an exception among the twenty-six ambassadors sent to Canberra since the American embassy opened in 1940. “My bottom line on this is that by and large the US has sent to Canberra generous campaign donors and political bagmen,” Curran says. “We usually get the runt of the American litter in this regard.”

The posting gained most attention in Washington when George H.W. Bush sent Republican fundraiser Melvin Sembler to Canberra in 1989, not long after he donated US$100,000 to the Bush election campaign. The controversy inspired a celebrated Doonesbury cartoon strip.

Several ambassadors have fitted the stereotype of a back-slapping networker, among them Harry Truman’s appointee Pete Jarman, a former member of Congress described as a “big, good-natured, Rotarian type of man,” and Lyndon Johnson’s envoy Edward Clark, a Texan lawyer and oil lobbyist who came to be known here as “Mr Ed” after the talking horse in the popular TV series.

But the appointees also include several highly experienced career diplomats, more commonly but not entirely when a Democrat was in the White House. The first two wartime ambassadors were long-time China hands, and William Sebald (1957–61), like Green, had been assistant secretary for East Asian and Pacific Affairs.

Bill Clinton used Canberra to show inclusiveness as well as diplomatic professionalism, with Edward Perkins, the first African American in the post, followed by Genta Holmes, the first woman. Obama sent John Berry, the first openly gay ambassador to a G20 nation.

In February 2018 another Marshall Green moment seemed to be looming when Donald Trump nominated the retiring US Pacific commander, admiral Harry Harris, who was noted for his strong views about standing up to China. “If we’d got Harry Harris, in my view, that would have been the first time since Green that we’d been given a real heavy-hitter,” Curran says. “The US alliance true believers were like Pavlov’s dog when they heard he was coming. They howled when he got diverted to the ROK [South Korea].”

A year later, after a record two-year vacancy, Trump sent Washington lawyer Arthur B. Culvahouse, best known for choosing Sarah Palin as running mate for Republican candidate John McCain in 2008 and Mike Pence as Trump’s in 2016. In Canberra he came to be known as an “honorary” member of the parliamentary group of China hawks.

Some of Australia’s top diplomats say that the two most effective American ambassadors of the past twenty years have come from outside the Foreign Service. Tom Schieffer (2001–05), a former business partner of George W. Bush in Texas, was in Washington with John Howard on 11 September 2001 and attended many of the war conferences about Afghanistan and Iraq. Jeff Bleich (2009–13) was an old lawyer friend of Barack Obama who helped guide the annual rotation of a US marine corps battle group through Darwin, the Australian end of the “pivot” to Asia.

Did the friendship of these political allies with their president make a difference to their usefulness to Australia? “Tom Schieffer did have a close relationship with Howard forged in 9/11, and as security and intelligence relationships got closer and closer in the post-9/11 period,” says Peter Varghese, former head of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Office of National Assessments, now chancellor of the University of Queensland. “But I can’t think of any intervention by Tom that was decisive. They help the flow that’s already got a bit of momentum and maybe give it a bit more momentum.”

Allan Gyngell, another former head of ONA and career DFAT official, and now national president of the Australian Institute of International Affairs, asked around about examples of successful interventions by US envoys. “The most specific response anyone could give was that we were able to fix a problem with steel tariffs through Tom Schieffer at some point in the Bush administration,” he says.

John McCarthy, who was Australian ambassador to Washington in the 1990s, also thinks Schieffer was the closest thing to a direct line to the president, and points out that he went from Canberra to Tokyo, a post usually reserved for very senior ex-senators.

But he says any US envoy here would struggle to get attention in the White House. “Most American ambassadors in Australia would pick up the phone and talk to the Asia guy in the National Security Council on almost any issue,” McCarthy says. “Or on a trade issue to one of the deputy US trade representatives. Or even someone lower down. It’s a question of how often you make the phone call.” Even a close presidential ally couldn’t ignore the State Department, where they would work with the assistant secretary for East Asia and Pacific Affairs.

“A US ambassador with a close relationship with the president is going to be very cautious about raising anything with him as US president,” adds Varghese. “In the US system it would have to be something extraordinarily important and urgent for even a friend of the president to use that relationship and burn up capital as it were.”

Significantly, the most recent crisis in the relationship, when Trump was considering including Australian steel and aluminium in his higher tariffs in 2017, was settled despite the US ambassadorship’s being vacant. Australia prevailed simply on the merits of the economic argument.

Allan Gyngell argues that a political appointee can be preferable because “Canberra never really gets a professional high-flyer, as opposed to a nice competent State Department person, anyway, because the job is just too easy — at least since Marshall Green had it.” The top people with the best connections will go to key postings like Moscow and Ankara. “But you could, of course, get duds of both types, and in the end the competence of the appointee is what matters most.”

Unlike the United States, whose ambassadors are nearly all White House–appointed, Australia normally has about half a dozen politically appointed ambassadors at any one time. Under prime minister Tony Abbott that grew to about nine, a number Varghese thinks will be exceeded in the future.

The conventional argument is that appointing a senior ex-politician to Washington means the Americans can deal with someone who has a direct line to our prime minister. And their former career and profile might also give political appointees better access to American leaders.

Varghese has his doubts. “The reality is that a career diplomat in Washington ends up having a direct line to the prime minister anyway,” he says. “It’s in the nature of the job and the nature of the prime minister’s interest. Dennis Richardson and Michael Thawley both had very regular contact with Howard when they were ambassadors.”

Are ex-politicians better at schmoozing Congress? “At one level, yes, because there’s a kind of a style to those interactions which comes very naturally to an ex-pollie and maybe not to a bureaucrat,” Varghese says. “But we’ve had professional diplomats who’ve worked the Hill very effectively, like Thawley, Richardson and Michael Cook.”

McCarthy, who had an earlier congressional liaison post in the Washington embassy, says the capital is full of former politicians, foreign ministers and even prime ministers appointed as their countries’ envoys. It is a constant battle for access, and ex-politicians are not necessarily the best at it.

“If someone is known to be a very senior politician it can help a bit,” he says. “But again the basic work is wearing out shoe leather.” Most of the time a foreign diplomat ends up seeing congressional staff rather than politicians anyway. “You have to understand how important these guys are. [Biden’s new secretary of state] Antony Blinken was a staffer, chief of staff of the House foreign affairs committee. These are the people you need to contact. They know their subject. They’re not really into the good-ole-boy stuff.”

Varghese and McCarthy both see political appointments working best in familiar, English-speaking capitals with an envoy — like Alexander Downer as high commissioner in London — who knows how to work the system back in Canberra. “I’m not one who thinks all political appointees are a waste of space,” says McCarthy.

But Varghese is generally sceptical. “Frankly, I worry deeply that our system is going to have more political appointments. It would be unrealistic to have none, but they are ultimately an act of patronage. They are dismissive of diplomacy as a profession. What they are basically saying is: anyone can do this job.”

In terms of presidential access, McCarthy gives the accolade to former ambassador Joe Hockey, who got to play golf with Donald Trump. “If a guy can get a couple of golf games with the president that’s a plus,” he says. “I certainly never could with Bill Clinton. I take my hat off to him.” Hockey had hoped to trade that closeness as a lobbyist in a Trump second term. “But now Trump’s gone, he’s stranded,” adds McCarthy.

Arthur Sinodinos, the former Liberal senator appointed in Hockey’s place, will now be working very strenuously to see Morrison isn’t stranded too. How long Biden waits to appoint an envoy to Canberra might be a gauge of his success. And a high-calibre envoy could be a reverse compliment: it might mean Biden sees Morrison as a problem. •

President Joe Biden nominated Caroline Kennedy as the next US ambassador to Australia in December 2021.