It started with such promise. On 4 February 2019, just three days after receiving the voluminous final report of the Hayne royal commission into banking, superannuation and financial services, prime minister Scott Morrison and treasurer Josh Frydenberg fronted the media to announce the government’s response.

They promised they would take “action” on all seventy-six of commissioner Kenneth Hayne’s recommendations to government. They would do everything necessary to empower regulators to hold to account “those who abuse our trust,” thereby demonstrating the government’s commitment to “ensuring a financial system that is working for all Australians.” (My emphasis.)

Over the two and a half years since then, those avowals have become increasingly hollow, even allowing for the unforeseeable six-month delay caused by the pandemic. While the treasurer’s media releases suggest all is well, it is only when you descend into the undergrowth of the reform process that the real state of progress becomes clear.

The government claims, for instance, to have enacted more than 80 per cent of Hayne’s recommendations. Yet more than half have been abandoned or watered down significantly, or are yet to be fully implemented.

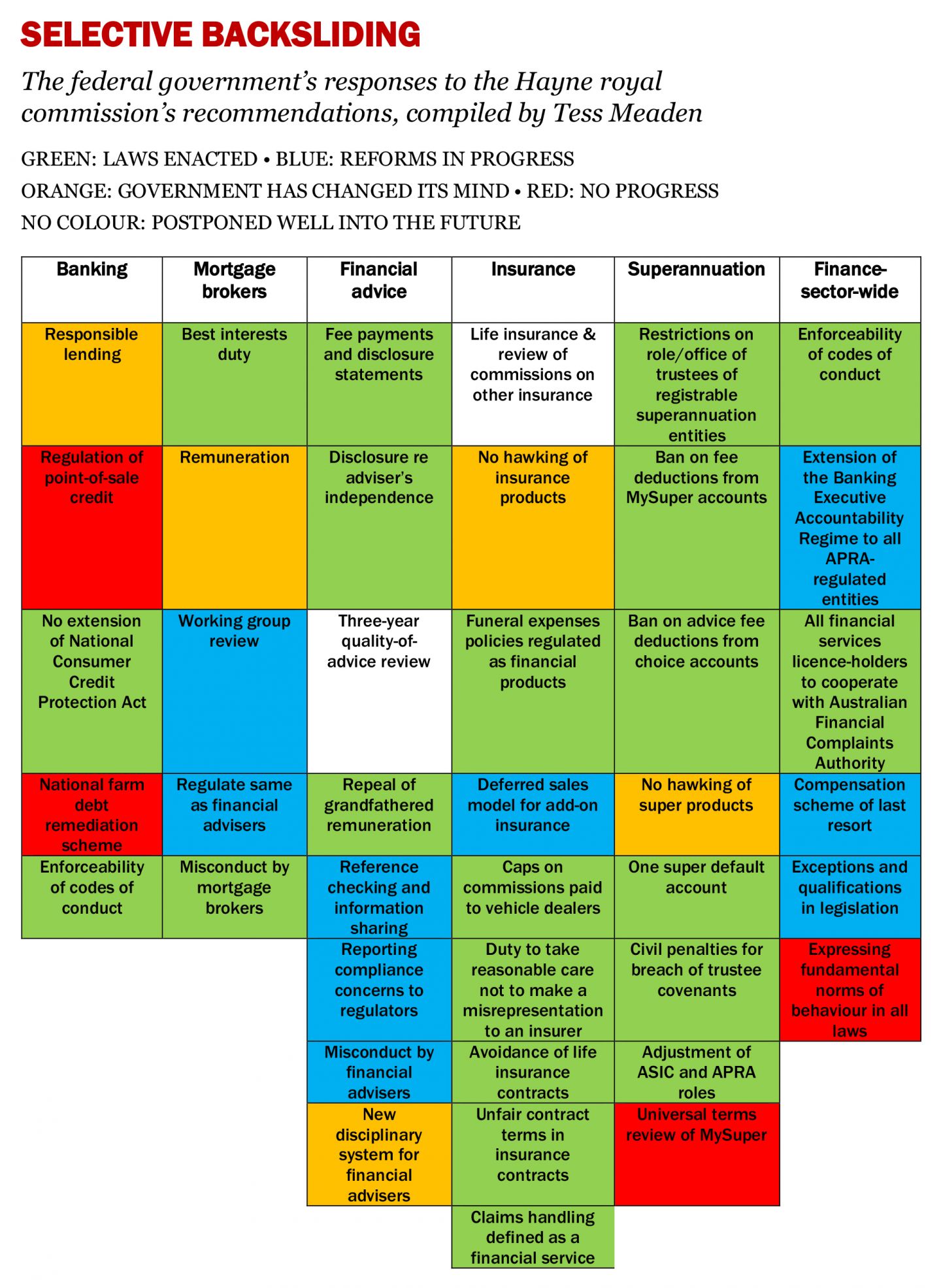

The chart below gives a snapshot of the government’s reform progress across five fields of financial activity: banking, mortgage broking, financial advice, insurance, superannuation, and sector-wide financial services. Only reforms that are the direct responsibility of the government are included; excluded are those that require action by regulators or industry bodies.

Green shading on the chart indicates where the government has enacted laws in line with its February 2019 commitment. Blue signifies reforms in progress but not yet completed; typically they are either in draft form or delayed by an uncompleted inquiry.

Orange signifies reforms the government originally committed to fully implement but later changed its mind about and offered something different. These reforms are weaker than Hayne’s recommendations, yet the government’s press releases imply they give effect to the commissioner’s wishes.

Red signifies the government has made no progress; and those with no colour have been put off well into the future.

If the government’s claims were correct, 80 per cent of the boxes in the chart would be green.

One group of recommendations in particular caught my eye: those marked in orange — the ones that the government has modified since its original press conference. Despite their different subject matter (responsible lending, mortgage broker remuneration, anti-hawking and a new disciplinary system for financial advisers) they all have the potential to fundamentally disrupt the business models of financial services firms.

Keeping that in mind, it’s no surprise to find that lobby groups have played a crucial role in the government’s evolving response to Hayne. Lobbyists for banks, mortgage brokers and financial advisers leapt into the void caused by the pandemic, taking advantage of delays in drafting legislation to convince the government to rethink its promised “actions.” The banks argued that the flow of credit to households and businesses needed to be free of impediment. Mortgage brokers pointed to the alleged risk of their own small businesses being destroyed, pushing unemployment higher. Financial advisers argued against any new regulations that could damage their businesses.

First cab off the rank were the mortgage brokers, who mobilised well in advance of Hayne’s final report. The government capitulations began on day one, when Josh Frydenberg revealed that, at least in the short term, the government wouldn’t be giving full effect to Hayne’s recommendations for that industry. This early lobbying success spurred on the bankers and the financial advisers.

Interestingly, the insurance and superannuation lobbies were either much slower off the mark or less successful in their campaigns. It is in relation to those two sectors that the government has passed reforms giving full effect to Hayne’s recommendations.

Governments capitulating to big lobby groups should be of real concern to those seeking to restore trust and confidence in our financial system. After all, as Hayne observed in the opening pages of his final report, “the primary responsibility for misconduct in the financial services industry lies with the entities concerned and those who managed and controlled those entities: their boards and senior management.”

In keeping with that central message, Hayne stressed the need to carefully monitor the culture, governance and remuneration practices of financial services entities. He recommended that the Banking Executive Accountability Regime, which has applied to senior executives and directors of banks since 2018, be extended to senior executives in all financial institutions within the scope of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, or APRA. The system, known as the BEAR, closely regulates the behaviour not only of banks’ senior executives and board members but also of banks themselves, and can result in large penalties.

The government has now made two attempts to develop Hayne’s proposed Financial Accountability Regime, the first in January 2020 and the second just last month. In the first version, senior executives of all regulated financial institutions would face the same obligations as set out in the BEAR. Importantly, the 2020 model also specified that individual executives and directors would be personally liable for their breaches of the act and could be subject to fines of up to $1.5 million. After public consultation, the 2020 model was withdrawn.

The July 2021 draft has one significant difference: it no longer provides for individual liability for senior executives and board members who breach their duties. The financial entities themselves can still be liable for civil penalties, and APRA can still disqualify people from holding the position of an “accountable person” within regulated entities, but this version has been stripped of individual penalties.

It is hard to see this as anything other than a major concession by the government to the banking lobby. Given Hayne’s core message, it stands to reason that the increased duties under the proposed Financial Accountability Regime would be accompanied by penalties. The banking lobby clearly saw this as a bridge too far and convinced the government to give way.

Abandoning individual liability also calls into question the sincerity of the government’s promise to restore confidence in the financial system. Ordinary Australians rely on regulators to monitor the large financial institutions and to act if significant misconduct is detected. If this misconduct tracks its way up to senior executives and boards, it follows that regulators should be able to take robust action against them.

The Financial Accountability Regime is not yet law, but the government anticipates the parliamentary process to be completed during spring this year and the laws to take effect in 2022. Of course, whether executives and directors of financial institutions have liability under the new regime or not, they remain exposed to penalties under the Corporations Act. But the Financial Accountability Regime is tailored to financial services institutions, and strong notions of responsibility and accountability — which seem likely to be watered down for those at the top of these organisations — should be integral to its effectiveness.

The government’s backsliding has also undermined responsible lending laws, which potentially affect every Australian who takes out a home loan. Existing legislation requires banks to lend responsibly to consumers — essentially to help people avoid over-committing themselves — and sets out how they should do that. Despite the importance of responsible lending laws, and despite calls from consumer groups to strengthen them, Hayne declined to recommend changes. Instead, he said, these laws should continue to operate exactly as they have since they were introduced in 2009.

The government initially agreed, only to backslide in September last year. Treasurer Frydenberg announced that the laws would be rolled back to apply only to a small number of credit contracts and consumer leases. He justified the backflip by referring to the recession caused by the pandemic, arguing that the repeal would remove “unnecessary barriers to the flow of credit to households and small businesses.” Yet Treasury, in its own submissions to Hayne, had conceded that these “barriers” had no material effect on the overall availability of credit and were likely to enhance rather than detract from Australia’s economic performance.

The treasurer’s justification echoed a lobbying campaign by banks and government backbenchers, and some wider criticism of what was described as the “academic” and “uncommercial” administration of the responsible lending laws by the Australian Securities and Investment Commission. The rollback legislation has been blocked by the Senate, however, so ordinary Australians might yet win this day.

And so to the less monolithic end of the industry. Australia’s 15,000 mortgage brokers are a critical intermediary between customers and banks, responsible for settling 59 per cent of household mortgages. Commissioner Hayne concluded that the industry is hopelessly conflicted, largely because of how its members are remunerated. Mortgage brokers purport to act for retail clients yet they accept upfront payments and trailing commissions from lending institutions. The only clear beneficiary of their services appears to be the mortgage broking industry itself.

To resolve that conflict, Hayne made four key recommendations. He proposed that brokers have a legally enforceable “best interests” duty to act in the interests of borrowers rather than lenders; that borrowers, not the lending banks, pay fees to mortgage brokers for their services; that all mortgage brokers eventually be regulated by the same laws that apply to financial advisers; and that a Treasury-led working group monitors and adjusts fees paid to mortgage brokers.

The government enacted the best interests duty, but the other three recommendations have been abandoned or reversed, or can’t proceed at least until after a working group reports in the second half of next year, almost four years after Hayne delivered his report. Until then, the much-criticised trailing commissions paid by lenders to mortgage brokers will continue, despite Hayne’s recommendation that they be banned. Also despite Hayne’s recommendations, mortgage brokers are unlikely to be regulated by the same laws applying to financial advisers.

The mortgage brokers’ swift and successful lobbying was all too evident at Josh Frydenberg’s press conference on 12 March 2019, where he exclaimed that “the government stands side by side with mortgage brokers.” Just a month prior, he and the prime minister had claimed kinship with “all Australians.” The government’s press releases brightly claim that the government has acted on Hayne’s mortgage broker recommendations. In fairness, it has — just not the action Hayne had in mind when he wrote three of his four recommendations.

Industry lobbyists argue that mortgage brokers’ conflicts of interest are now well regulated by the best interests duty and the government’s new ban on mortgage brokers accepting “conflicted remuneration.” The definition of what constitutes “conflicted remuneration” is complicated, but as the law currently stands, it doesn’t necessarily rule out brokers being paid the very commissions that Commissioner Hayne wanted prohibited. Unless things change following a review scheduled for late 2022, mortgage brokers will continue to operate with the same conflicts.

Finally, what of financial advisers? Their campaign for change has really only just begun. Much of what follows for that industry depends on the outcome of a 2022 review of the effectiveness of existing measures to lift the quality of financial advice. But signs already suggest that the government is bowing to pressure to water down the new disciplinary system for financial advisers.

Hayne expressed concern that the current system is top-heavy with penalties that are really only appropriate for the most serious cases of misconduct, which means that less serious misconduct escapes sanction. He proposed a new disciplinary system quite separate from the Australian Securities and Investment Commission’s power to ban financial advisers. The government initially proposed that this function be taken up by the regulator, the Financial Adviser Standards and Ethics Authority. But in December last year that proposal fell victim to lobbying from the industry, which sees ASIC as more accommodating of the industry’s commercial concerns. The government’s subsequent announcement that the disciplinary role would be taken up by ASIC’s Financial Services and Credit Panel was hardly consistent with the spirit of Hayne’s recommendation.

Signs suggest that the backsliding won’t end there. Members of the government have recently begun expressing broader doubts about Hayne’s reforms. Last month Tim Wilson MP, chair of the House of Representatives economics committee, publicly questioned the thinking underpinning Hayne’s final report and complained that the government felt obliged to accept the commissioner’s approach. Treasurer Frydenberg has pressed ASIC to prioritise supporting Australia’s economic recovery from the pandemic, leaving open the question of how it goes about that task while enforcing the law in the manner recommended by Hayne.

The upshot of all these commitments, capitulations, delays and obfuscating press releases is that the fate of Hayne’s reform agenda is unclear. The commissioner’s final report expressed concern about the connections between misconduct and financial reward, the effect of conflicts of duty and interest, and the need to hold entities to account. The treasurer has reported on the government’s success in “taking action” on these issues while quietly modifying reforms to reduce their impact on bankers, mortgage brokers and financial advisers. Ordinary Australians, meanwhile, lack virtually any influence over the process. •