Destination Elsewhere: Displaced Persons and Their Quest to Leave Postwar Europe

By Ruth Balint | Cornell University Press | US$45.00 | 190 pages

Just a few months ago the Refugee Convention — “a cornerstone of refugee protection,” according to the UN refugee agency, the UNHCR — turned seventy. In conjunction with its 1967 Protocol, the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees defines who is and who isn’t a refugee, and sets out refugees’ rights.

The anniversary well-wishers included German foreign minister Heiko Maas, who said the convention “was drawn up in view of the immeasurable suffering that millions of people were forced to endure during and after the second world war. Its clear aim was to ensure that this could never happen again.” He also reminded us that more than eighty million people are currency displaced — a fact that made the convention “indispensable today.”

With these words, Maas conjured two sets of images. His “never again” was clearly a reference to the Holocaust, perhaps evoking the black-and-white photographs of emaciated survivors taken by the Allies immediately upon the liberation of the concentration camps. And his mention of today’s displaced people would have reminded his audience of televised footage showing thousands of predominantly Syrian refugees making their way through Hungary and Austria in the summer of 2015, or masses of people living in squalid conditions in refugee camps in Africa or Asia.

Neither of these sets of images has much to do with the origins of the Refugee Convention. Yes, two major refugee crises in the second half of the 1940s produced images akin to those that we might see today depicting refugees from Syria, Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo or Venezuela. But neither of those early postwar crises — the Nakba, which displaced some 700,000 Palestinians, and the Partition of India, when more than ten million people fled or were driven from their homes — were much discussed among those negotiating the Refugee Convention.

Instead, their attention was focused on what were known as “DPs,” or displaced persons. Millions of people had found themselves outside their country of origin at the end of the war. Most of them had been swiftly repatriated — some, against their will, to the Soviet Union. But by 1946, about a million DPs were still stuck, most of them in the French, British and American zones of occupied Germany.

Despite the war still being fresh in their minds, the drafters of the convention had set out to tackle the consequences rather than the causes of mass displacement. They wanted a convention that defined the status of displaced people rather than dealt with their “immeasurable suffering.” Resettlement wasn’t even designed solely for their benefit. When Eleanor Roosevelt warned the UN General Assembly in December 1946 that the DPs’ presence was delaying “the restoration of peace and order in the world,” her chief concern may well have been to prevent a potentially volatile situation in the DPs’ host societies, particularly in Germany and Austria.

Most of the DPs were from Poland, Yugoslavia, the Baltic states, the Ukraine and other countries in Eastern Europe. Most were stranded in Germany and Austria because that’s where they had been taken as prisoners of war or forced labourers during the war. Some were in Italy, the Middle East, East Africa, India and China, and some were Jewish survivors of the concentration camps.

In other words, today’s international refugee regime originated not in the refugee crises in the Middle East and on the Indian subcontinent in the second half of the 1940s, and not in the Holocaust (or in the earlier failure of nation-states to provide a refuge for European Jews). It lay in the anxiety provoked by DPs in the second half of the 1940s and the early 1950s, and in the effort to resettle the “last million” — initially to countries in Western Europe, but soon to Israel, Australia and the Americas.

The role of the “last million” in international discussions about the attributes and rights of refugees and in the making of international law is a key reason why studies of the DPs are so relevant to today’s debates. Much has already been written about the International Refugee Organization, or IRO, which was given the job of facilitating the resettlement of DPs, and much about the resettlement of DPs in Australia and other countries. Ruth Balint’s immensely readable and highly original book Destination Elsewhere adds to that scholarship. What makes her contribution particularly valuable is her concern not so much with the IRO or the reception of DPs in Australia and elsewhere, but with the DP experience.

Most importantly, Balint shows how the question of who ought to be counted as a refugee played out not just in the conferences where diplomats and international lawyers haggled over the definition used by the IRO and the terms of the draft Refugee Convention, but also in submissions by DPs, in interviews with DPs and, more generally, in the autobiographical narratives DPs fashioned to bolster their identity as refugees. The question, what were the grounds for a DP’s eligibility as a refugee?, runs like a thread through the book’s seven chapters.

Balint is less interested in the content of policies than in how they were implemented and how much wriggle room they provided. Drawing on dozens of cases, she explores not only how policies and practices affected the lives of individuals, but also how individuals negotiated their way around existing rules.

The cases featured in Destination Elsewhere are complex. Among them is that of Arthur W., a non-Jewish German married to a Jewish woman who had survived the Holocaust — not least, I imagine, because she was protected by his having resisted the pressure to divorce her. Arthur himself had been imprisoned in a concentration camp from 1944 until the end of the war, and was initially classified as a refugee, which would have allowed the couple to emigrate to join their son, who had left Germany ahead of them. But just as they were about to embark to the United States, the IRO realised it had made a mistake. Like other non-Jewish husbands of refugees, and unlike the wives of eligible refugees, Arthur was deemed ineligible for IRO assistance.

Also ineligible, but for very different reasons, was a couple whose son Gabor had a disability. Their application to settle in Australia was rejected, according to their emigration file, “because the child is a mongolian idiot.” The IRO advised the parents to leave Gabor behind. They separated over the issue, with the father emigrating after their divorce and the mother remaining with their son. A year later, the mother changed her mind and consented to separate from Gabor permanently.

Or consider the case of Gregor L., aka Michael Kolossov, a Red Army officer who defected in 1945 and was then advised by an official in the American zone to conceal his Russian identity. Changing his name, date of birth and nationality (and now claiming to be of Polish Ukrainian origin), he, his wife and their two children lived for four years as DPs in the city of Wiesbaden, near Frankfurt, until they were accepted for resettlement in Australia. There, Gregor came clean, telling the authorities of his former identity, because, he said later, “I wanted to show that I was honest and loyal.”

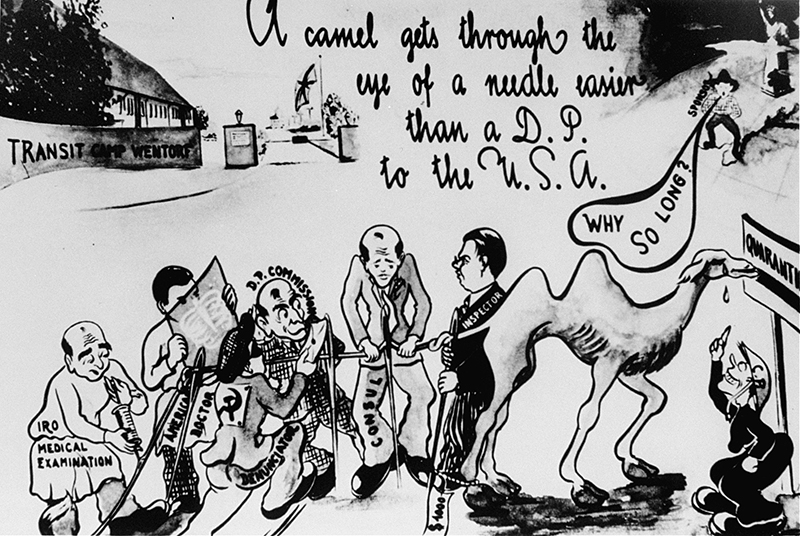

A 1946 cartoon illustrating the obstacles impeding the emigration of displaced persons to the United States. The DP camp depicted in the background is identified as Wentdorf. Gedenkstaette Bergen-Belsen

The Australian authorities were “less interested in protecting Communist defectors than they were in sheltering Nazi ones,” as Balint dryly notes, and promptly declared him a security threat. His case received sympathetic attention in the Australian press, but he was deported back to Germany. Because the Australians told the IRO that they suspected him of having worked for Stalin’s secret police, the Americans kept him under close surveillance in Germany as a possible Soviet agent while inviting him to participate in the Harvard Project, an attempt to gather intelligence about the Soviet Union by interviewing refugees. The researchers much valued Kolossov’s assistance, with one of them later praising his “sincerity” and “objectivity.”

Concerning this last case, Balint tells us that the family may have lived in Germany until 1955 and then emigrated to Canada, but concedes that “even this is unclear.” In most other cases, we don’t learn what eventually happened to her protagonists. As a reader, I found the fragmentary nature of these accounts of DPs’ lives intensely frustrating. What became of Arthur W.’s family? Were they eventually resettled? If they weren’t, how did they fare in the country where they had been persecuted? Did their son return to Germany? And what about Gabor? Were his parents able to make a new start?

Arthur W.’s story also raises the question of whether he provided the IRO with a truthful account. Had he really been imprisoned in a concentration camp? If so, on what grounds? Such questions suggest themselves even more so in Gregor L.’s case. Was he also “sincere” and “objective” when it came to retelling his life? Was he identical with Michael Kolossov, or was L., as the Australians claimed, someone else altogether?

Of course this was not meant to be a book about the life histories of refugees. And the effort involved in comprehensively researching that many lives would have been considerable and, given the focus of the book, unreasonable. In fact — on second thoughts — I suspect that it may be the individual stories’ open-endedness that makes the text strangely intriguing and prompted me to read on. At the same time, the lack of closure focused my attention on the issues that the cases were meant to illustrate.

Historians trying to turn the past into a narrative tend to be influenced by at least three factors: their own present, the availability of sources, and what I would like to call the course of history. No historian is immune from these influences. But how they shape a historical narrative depends also on how much the historian is aware of, and able to respond to, them.

As Balint has demonstrated in her other books (most recently in Smuggled, which she co-wrote with Julie Kalman and which also came out this year), she is what the French call an écrivaine engagée, a writer who is perturbed and at the same time motivated by her own present, not least by its injustices. She is troubled by the categorical and seemingly unproblematic distinction between political refugees and economic migrants today, and aware of how much a person’s recognition as a legitimate refugee depends on their ability to offer a convincing narrative about their life. She knows that the more truthful the narrative the more convincing it is — but that here “truth” is in the eyes of the beholder, and depends on what seems credible to somebody else: for example, a person working for the UNHCR, an immigration officer or a judge.

Balint is appalled by the fact that the response of her own country, Australia, to people seeking its protection often doesn’t reflect the international treaties it has ratified, be it the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, or the Convention on the Rights of the Child. “Australia’s immigration laws still require all migrants to be screened for medical conditions, so as to prove they will not be an economic burden on the community,” she writes. “This affects children most of all.” In October, Australian Paralympic athlete Jaryd Clifford recalled the case of Pakistani refugee Shiraz Kiane, who twenty years ago set himself on fire outside Parliament House because the immigration department objected to his family’s joining him in Australia on the grounds that his daughter’s medical treatment would be too expensive.

“The book is a work of history concerned with the present,” Balint writes. Because she, like Clifford, is troubled by the present, she is particularly sensitive to instances in the past in which the present is prefigured. As she avoids any moralising, this honing in on historical issues to which she is particularly attuned adds a degree of passion to her text that contributes to its readability.

Balint is acutely aware of the second factor shaping her narrative, the limitations of her archive. Her book “began with a chance visit” to the International Tracing Services archives in Germany, which holds records relating to seventeen million people and had only recently been opened to researchers. This visit appears to have prompted her to consult the IRO’s records, which are held at the National Archives in Paris. And there she discovered the decisions of the IRO Review Board, which became a main source for her project.

Because of the richness of the review board’s files, the cases featured in her book tend to be complex and were contested at the time. But the majority of refugee status determinations involving DPs were presumably comparatively straightforward, which means that they didn’t leave an extensive paper trail. Balint’s reliance on the records of the review board partly explains why she was rarely able to say what eventually happened to people like Arthur W. and Gregor L.; for obvious reasons, the review board took no further interest in the fates of individuals once it had arrived at a decision.

The fact that archives are not merely repositories that can be mined to answer the historian’s questions is not peculiar to Balint’s project, but I wish she had taken her reflections about the peculiar archival further —that may be a suggestion for another text, however, one that engages with the peculiar challenges posed by archival research about refugees. In Destination Elsewhere, Balint seems to take shelter behind fellow historians Carolyn Steedman and Natalie Zemon Davis, who have both reflected on the historian’s reliance on and engagement with archival sources. “Nothing starts in the Archive, nothing, ever at all, though things certainly end up there,” Steedman writes. “You find nothing in the Archive but stories caught halfway through: the middle of things; discontinuities.”

Finally, the narratives produced by historians are informed by a presumed course of history. When looked at it with the benefit of hindsight, the so-called DP problem seems to have come about because many Eastern European DPs could not or did not want to be repatriated, and it was largely solved when a handful of countries of immigration — most prominent among them the United States, Australia and Israel — offered to resettle hundreds of thousands of people stuck in Central Europe. That outcome was in the interests of the Allies, who were responsible for looking after the DPs; of the IRO, naturally; of host countries Germany, Austria and Italy, much of whose infrastructure was in ruins and some of whose people were starving; of countries of resettlement, like Australia, that were experiencing a labour shortage; and of the DPs themselves, who often wanted to get away from Europe.

But it was by no means self-evident that resettlement would be the answer to displacement. I can think of only two other instances in which people who were displaced because they fled, or otherwise found themselves outside, their home, were swiftly resettled. One concerns refugees who fled Hungary to Austria or Yugoslavia after the failed 1956 uprising and ended up in pretty much the same countries that had accommodated DPs in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The other relates to concerted international efforts to resettle Indochinese “boat people” stranded in Indonesia and elsewhere in Southeast Asia.

But both before, during and after the second half of the 1940s, comprehensive resettlement schemes were the exception. Think of the Armenians in the early twentieth century, for example, or of the Palestinians in the late 1940s, or of Eritreans, Afghans and Syrians today, not to mention Jews desperate to leave Central Europe in the late 1930s. Resettlement was rarely an option for them. And when Polish or Latvian DPs first decided that they did not want to return home, they could not yet know that resettlement outside Europe would be the alternative to repatriation. Initially at least, they had to assume that they would have to remain in Europe, if not in Germany.

Only the course of history encourages us to think of the DPs’ lives in postwar Germany in the context of a trajectory that culminates in a country of resettlement. The course of history encourages us to focus on the DPs’ “quest to leave postwar Europe,” to quote the subtitle of Balint’s book. But not knowing that they might soon settle in the United States or Australia, DPs busily created social networks unrelated to their emigration.

Adam Seipp’s Strangers in the Wild Place, which I reviewed for Inside Story some years ago, illustrates the varied contacts of residents of the Wildflecken DP camp. Outside the camps, DPs interacted not only with members of the Allied occupation authorities but also with locals. In the camps, they carved out spaces where they could be in charge of their own affairs. In some camps, they elected representatives and staffed administrative bodies. They supported a vibrant cultural life. Most important, they created formal and informal networks of compatriots-in-exile and strengthened such networks and associated multiple identities through the publication of periodicals. In Germany’s American zone alone, twenty-nine newspapers and thirty-nine magazines published by and for DPs were counted in December 1947.

The course of history encourages us to think of resettlement as the norm for DPs. In places like Australia, history evidently continued. The arrival of a large number of DPs changed Australian society and helped to prepare it for a multicultural future. By contrast, the fact that a sizeable number of DPs could not be resettled and had to remain in Germany and Austria appears as a dead end. But these remaining DPs too made history. Categorised as heimatlose Ausländer (“homeless foreigners”) in West Germany and generally referred to as the “hard core” by the UNHCR and aid agencies, they acquired many of the rights usually reserved for German citizens but were nevertheless relegated to the margins of society.

From the perspective of 2021, the heimatlose Ausländer seem at least as representative of the modern refugee as Arthur Calwell’s “beautiful Balts.” And much like the experience of the “last million” tells us something about the origins of the 1951 Refugee Convention and the modern refugee regime, the lives and narratives of their “hard core” remnant, and their interactions within German society, ought to be indispensable reference points for a history of the Federal Republic.

Ruth Balint’s book is about the making of history by DPs in the sense that the period in the late 1940s and early 1950s that saw the resettlement of most of them “had a lasting impact on the definition of the refugee, the development of international law, and the creation of a modern, bureaucratic refugee regime.”

Her book is also about the crafting of histories by people who realised that the IRO and prospective resettlement countries were less interested in their wartime suffering, and more in a perceived Red menace, which led DPs to “[articulate] a narrative of persecution and [to valorise] their predicament in line with Western anti-communism.” That narrative established their credentials as refugees. Whether or not the histories that emerged in submissions and interviews were factually true is often impossible to establish. But that’s beside the point, at least as far as the argument in this excellent book is concerned. •