Shooting Through: Campo 106 Escaped POWs after the Italian Armistice

By Katrina Kittel | Echo Books | $34 | 398 pages

Ken Inglis, that great Australian scholar, used a simple measure when considering new writing: does it tell us something we don’t know? Shooting Through does. Katrina Kittel’s first book adds much to what we know about Australian prisoners of war in Italy during the second world war. This is an important work.

The second half of 1943 brought chaos to Italy, with the collapse of Mussolini’s fascist regime and then, in September, surrender to the Allies. Allied forces landed on the Italian mainland and began their slow advance northward, opposed by German soldiers sent to defend the peninsula. With the collapse of the Italian war effort and the state’s bureaucracy, the prison system that held Allied POWs faltered.

Some Allied prisoners simply walked away, unchecked by the Italians who once had guarded them. That was the easy part; the hard part was finding a way to freedom, which often involved picking a way past Italian fascists, aggrieved by developments in the war and looking for violence, and through the German forces that had flooded northern and central Italy to defend the Gustav Line. Many escapers made for the Alps and tried to cross into neutral Switzerland; others went south in the hope of locating Allied lines and finding sanctuary behind them.

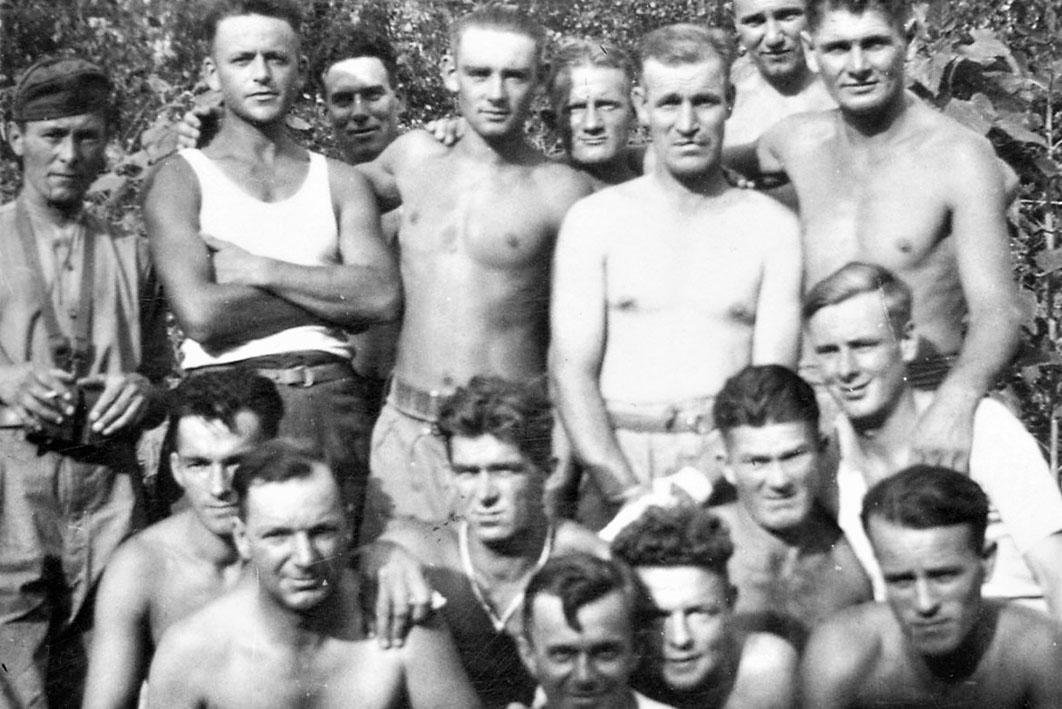

As the book’s subtitle indicates, Kittel has a particular focus. She follows the prisoners of Campo 106 and their bids for freedom in the weeks and months after Italy’s surrender. Her father, Col Booth, was one of those who “shot through” from Campo 106, and her impulse to learn about her father’s war led her to more stories of Italian captivity and escape, and to significant civilian histories. Woven through the book are interesting portraits of Italian men and women who helped, and sometimes hindered, escaped POWs. Kittel has done well to find these stories, which illuminate aspects of Italian life under fascism and occupation. Careful and determined research informs the narrative.

The image of bumbling, comical Italian soldiers has dominated Australian perceptions of the war against Mussolini and life in Italian captivity. Early in the book Kittel writes of Australian soldiers who duped their Italian captors into believing they didn’t know how to use a shovel, prompting the credulous Italians to offer digging instruction. Surely this is a story that grew in the telling, a tale conforming to the stereotype of the larrikin Aussie soldier and the dopey, pliable “Ities” who served Mussolini. I mention the passage not because it’s typical, but because it sticks out from the narrative as wholly atypical. One of the best things about this book is that Kittel deftly avoids tired caricatures of Aussie diggers and incompetent Italian soldiers.

Given a choice, POWs would have chosen Italy over Changi or the Thai–Burma Railway or the Sandakan death marches, but it doesn’t follow that captivity in Italy was benign, as perception and written histories often have it. Colonel Vittorio Calcaterra, commandant of Campo 57 at Gruppignano and a committed fascist, was infamous among Australian prisoners for his brutality. He and his thugs inflicted cruel and degrading punishments on POWs, forcing sick men to stand on parade in sub-zero temperatures, and stripping, chaining, starving and beating other prisoners.

For all the physical suffering of POWs, captivity made deeper wounds on the mind. Kittel shows that the circumstances of imprisonment matter less than what prison represents: the theft of an individual’s freedom. The book thus prompts readers to consider a radical and important thought: did prisoners of Italy suffer the same level of mental torment as prisoners of Germany or even of Japan, the gold standard for measuring POW misery?

The question is implicit, for Kittel wisely avoids linking her story to the experiences of Australian POWs in the Asia-Pacific theatre. Much of the limited literature on Australian POWs in Italy is shaped by an unhelpful tendency to examine the Italian experience relative to events in Asia. Details of beatings at Changi reveal nothing about what men endured at Campo 57 or 106 or elsewhere in Italian POW camps.

Nor was the pursuit of freedom some sort of boys’ own adventure in bucolic Italy. Kittel’s subject matter came with risks, for it is the stuff of schoolyard daydreams, feats of derring-do hard to comprehend. But she succeeds in telling these stories without injecting a false note of romance, never trivialising escapes as exciting jaunts. Fear and death stalked the men all the way to Switzerland or Allied lines, and they often went without food and shelter. If they reached the Alps they then had to cross them, challenge enough in peacetime. In civilian clothes behind enemy lines they forfeited the protection of the Geneva Conventions; capture could mean being declared a spy and executed. Some Australian escapers in Italy were murdered by Italian fascist soldiers. The physical and mental burdens incurred in “shooting through” were as heavy and damaging as those imposed by captivity.

In the final two chapters, the best in the book, Kittel considers how the experience of captivity shaped the postwar lives of these POWs. She writes movingly about the pleasures and difficulties of returning home to families and communities who offered warm welcomes and love, but rarely understanding. I hope that in these two brief chapters is the kernel of a new book, a companion volume to Shooting Through.

In places Shooting Through is overwritten, the metaphors clunky. Some sentences seem to have been written around certain words and phrases, with language chosen for effect rather than to make sense of the story. Kittel’s habit of avoiding good, simple words for sexier alternatives can rankle: “diarised” or “scribed” instead of “wrote,” “trundled” instead of “drove,” “spearheaded” instead of “headed,” “toddled” instead of “walked.” Does anyone in a war zone “toddle”? Rather than lifting the story, this language intrudes, especially given the power of the raw material: these histories don’t need embellishment. There is a sprinkling of typos and misplaced apostrophes through the book, most in the last third of the manuscript. A sterner, more careful edit was needed.

But these are quibbles. Shooting Through helps us better understand the experiences of Australian soldiers imprisoned by Italy in the second world war, a significant but little discussed chapter in Australian military history. Kittel has done Col Booth and his mates proud. •