Literary Lion Tamers: Book Editors Who Made Publishing History

By Craig Munro | Scribe | $29.99 | 288 pages

When I started working as a publishing assistant in 1990, a low-level agitation rumbled from houses big and small, multinational and independent, trade and educational. The issue of concern was women’s representation, both as named authors on jackets and as employees sitting at decision-making tables. I recall going to various Women in Publishing meetings, and at least one weekend conference, where experience and information was shared alongside “networking activities.” They were as much about career development as any feminist game plan. Admittedly, those may have been the same thing.

Thirty years later I didn’t so much leave book publishing as swap sides, becoming a full-time writer in 2020. Thankfully, agitation about better representation had continued, latterly picking up pace and ambition. The game-changing impact of the Stella Prize, created in 2012, led to the Stella Count, which moved in turn from measuring diversity on the basis of a male–female binary to recasting diversity in a more intersectional way. Not long before my official last day, a brilliant young colleague sent a thoughtful reply-all email to our CEO asking what we were doing to improve representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and people of colour as in-house staff, freelance editors, designers and, indeed, authors on our list.

Craig Munro’s engaging Literary Lion Tamers made me think about all this, describing as it does an arc of change — and sometimes a lack thereof — much longer than my own career. But this book is not so much about how the publishing industry, by closely reflecting society and culture, thus reflects readers’ own society and culture back to them. Instead, it focuses on the labours of getting those books out. And while I say “industry,” this book suggests that Munro would be the first to agree that the term overstates what were well-intentioned but often shambolic local publishing efforts.

At least before the 1950s, that is, by which time being published no longer meant being published in London. By then, Angus & Robertson employed almost 600 staff in Australia, London and New Zealand, a figure greater than I expected. What didn’t surprise me was that most employees worked in the company’s bookshops and in its Kingsgrove printery in Sydney rather than at desks wielding red pencils.

Munro’s book is a hybrid — anecdotal memoir, literary history, publishing history and a collective biography of editors and the writers they worked with. I liked the strong title, though many of the “lions” were less kings and queens of the jungle than alcoholic, broke, stuck or resistant to having their words cut. (Looking at you, Xavier Herbert.) As I considered the book’s subtitle, I could hear the voice of a marketing manager I worked with saying, “Do we need to say ‘book editors’? The reps will hate it.” But the title and subtitle describe what the book is about, if hyperbolically, which means they are doing their job just fine.

Literary Lion Tamers is a companion to Munro’s previous book, Under Cover, a more detailed personal history of his years at the University of Queensland Press in the Brisbane suburb of St Lucia. His illustrious career there started unpromisingly, as so many do, with the endless photocopying of proofs. But, apropos the subtitle, Munro ended up making history himself, first as UQP’s fiction editor and later as publishing manager. Less gossipy than Under Cover, given the focus here is on other editors, this book complements the first. They have complementary cover designs, too, and overlap in content. A priceless account of Peter Carey and a boozy recording gone wrong, for example, appears in both.

The current book ranges through editors, authors and books with which the author has some connection, tenuous or not, or that he admires. In the case of writer and editor P.R. “Inky” Stephensen, whose move from the radical left to the nationalist far-right he covers here, Munro displays what we might call an obsession; his early promise that Stephensen will be the book’s most flamboyant literary lion tamer is true. Munro once slogged through Stephensen’s papers, thousands of hours of primary research that led to his 1983 PhD, a prize-winning 1984 biography and many pages of this book.

Craig Munro’s own career shows that sliding-door moments don’t always block off alternatives. A writer as well as a publisher, he has also worked as a journalist and an academic. Indeed, the first anecdote in the book is about attending a Commonwealth literature conference in Fiji, which takes on the air of one of the Somerset Maugham stories he read on the plane to Suva. He has a novelist’s eye for detail. In one passage about critic and editor A.G. Stephens, who he says would now be described as a public intellectual, Munro writes that Stephens’s wife Constance used to cut up his food into small pieces so he could read and eat at the same time.

The “perennial problem of sales” — that need to balance literary art, schlock and everything in between with commerce — is a theme of the book and, let’s face it, the biggest theme of publishing itself. As anxious publishers hoping for a bestseller click to check the latest BookScan figures, they will concur with Munro’s rueful comment: “I was often disappointed when the books I’d edited failed to generate any profits at all.”

If Inky Stephensen is the main character in the book, the Bulletin would be the main literary institution. Munro quotes an article from the Bulletin’s famous Red Page in which Stephensen rashly predicted sales of 6000 for each new title to be published by his Endeavour Press, just launched. There’s no surprise in the revelation that Endeavour Press didn’t last long.

I enjoyed Munro’s evocation of the process and craft of book publishing: dog-eared manuscripts read, assessed, rewritten and later marked up and typeset before proofing. It’s a world of sharpened pencils and delicate negotiations. He delights in the book as an object and knows what it takes to make a beautiful one. “Under white dust-wrappers, the black-and-gold case lining of these small squarish books felt — and looked — like snakeskin,” he writes at one point. “Each volume shared the same attractive typography and page layout. The generous point size and line spacing meant that a novella, or even a few short stories, filled more than a hundred pages.”

Critic and writer Geoffrey Dutton criticised Stephensen in the 1960s for being “more than twenty years out of date,” and many of the books by the literary lions are coming up to being a century out of date. Some, such as Joseph Furphy’s Such Is Life (edited by A.G. Stephens) are still in print, as is They’re a Weird Mob, both reissued by Text. Finding Steele Rudd’s On Our Selection is easy enough, but I can’t imagine many seek it out. Who can be surprised that bestselling travel and history writer Frank Clune, many of whose books were ghostwritten by Stephensen, is no longer in print?

Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria, meanwhile, will last longer than Xavier Herbert’s Capricornia, and deserves to (though Herbert’s Poor Fellow My Country, supposedly the longest Australian novel ever published, is available as an ebook). Writers such as D.H. Lawrence, who makes an appearance thanks to Stephensen’s involvement in London with an edition — possibly pirated — of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, are simply unfashionable.

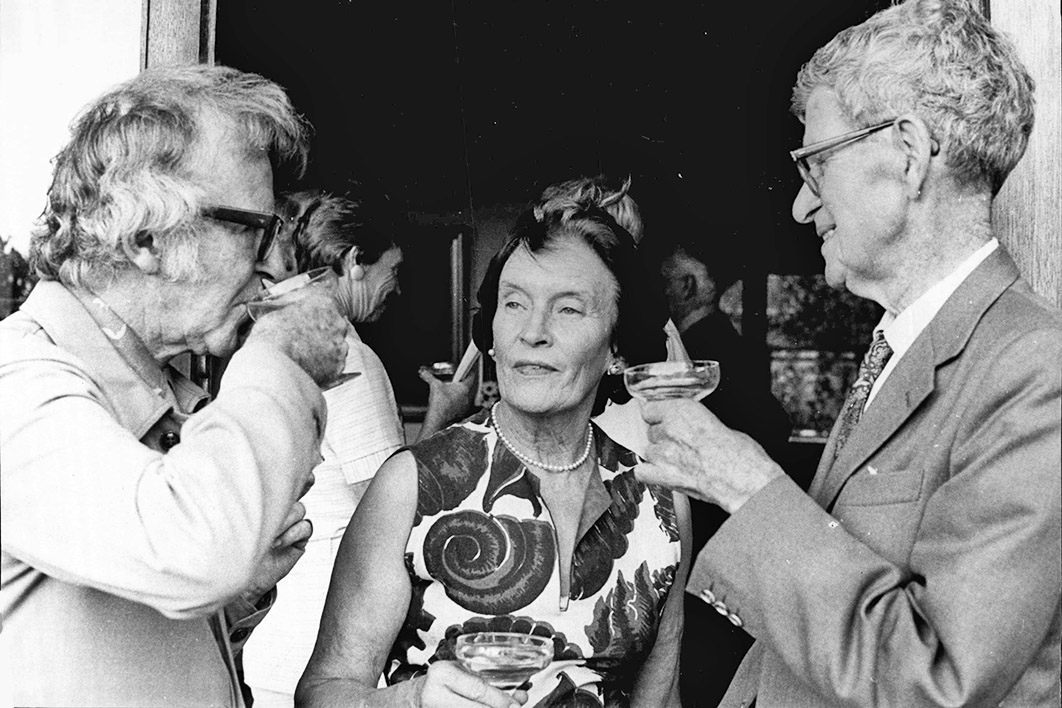

When famed A&R editor Beatrice Davis enters the scene, she brings more books and authors likely to pass the test of time. We get a sense of her deep commitment to her authors, though not to Frank Moorhouse — she argues against A&R’s publishing The Americans, Baby. I published Jacqueline Kent’s revised biography of Beatrice Davis and Eleanor Hogan’s (forthcoming) biography of Daisy Bates and Ernestine Hill, so I’m definitely among the target audience. But reading Davis’s correspondence with Ernestine Hill was compelling, if excruciating, and Davis’s — and Munro’s — descriptions of the troubled Eve Langley, author of The Pea Pickers, are as tragic as when I first read them.

Falling within the span of my own career are the New York diary entries of Rosie Fitzgibbon, Munro’s long-time UQP editorial colleague and recipient of the first Beatrice Davis Editorial Fellowship. The immediacy of Fitzgibbon’s accounts, and their practical wisdom, accentuate her loss to the publishing world. “In New York everything requires time-consuming investigation,” she writes, “and the constant need to present yourself in the best possible light to so many new people day after day is exhausting.”

Fitzgibbon was clearly up to meeting the challenge. Her papers, like so many others that form this book, are in the Fryer Library at the University of Queensland, which Munro describes as his own literary Tardis. The book begins and ends there.

Munro was no doubt gentle with his authors, and the book has that tone, with no false nostalgia. Corporatised and digitised modern publishing may be, but in its warm, discursive way this book makes the point that the work that publishers, editors and writers do hasn’t changed as much as we might think. •