It takes a certain chutzpah to proclaim that you are building a brand new economic model when the supermarkets are short of food, you’ve called in the army to help deliver fuel, and record gas prices have left whole industries on the brink of closure. But brazen cheek is one thing Boris Johnson has never been short of. He even had enough of it to holiday in Spain this week in the middle of Britain’s energy crisis.

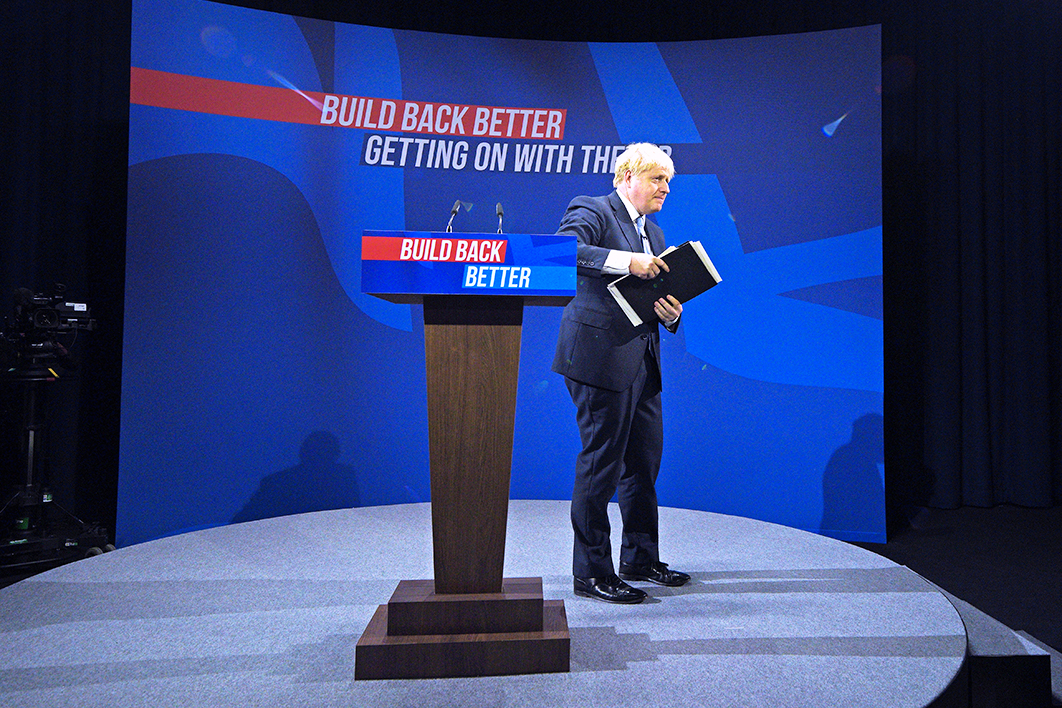

Johnson’s claim — made in an upbeat, joke-strewn speech to last week’s Conservative Party conference — looked like a novel way of brushing aside Britain’s current woes. The country’s troubles, he said, were just the growing pains of the country’s post-Brexit transition to a “high-wage, high-productivity economy” no longer dependent on immigrant labour. Castigating both Labour and Tory governments over the last thirty years for failing to deal with structural weaknesses, he declared that his administration would at last fashion a different and better kind of economy.

To most observers Johnson’s optimism seemed outlandish. Britain is currently experiencing a welter of economic problems. Tens of thousands of East European workers have gone back home since Brexit, leaving critical labour shortages in key sectors. A scarcity of lorry drivers has meant long queues at garages; too few seasonal fruit pickers has left produce rotting in the fields; an exodus of abattoir workers means healthy pigs are being shot on the farm. Not just supermarkets but toy shops are warning they will be short of stock at Christmas. As global gas prices rocket, meanwhile, Britain has been hit particularly hard. The government is subsidising vital fertiliser-making plants; energy-intensive industries such as steel and paper are desperately seeking government support to stay solvent.

The idea of drawing anything positive out of this might be dismissed as fantasy. After all, Johnson can’t argue that losing so many immigrants was simply misfortune: this was precisely what the “Leave” campaign he led during the Brexit referendum promised voters. With a small exception for 5000 lorry drivers (and only till Christmas), the government has steadfastly rejected business pleas to issue more visas for key workers, instead telling industry bosses that if they want more staff they should pay higher wages. Yet it is already painfully obvious that this won’t be enough: in key sectors there simply aren’t enough workers in the population both sufficiently skilled and willing to do the manual work previously done by East Europeans.

And yet Johnson also has a point. For it is indeed the case that over the past four decades Britain has become a predominantly low-wage, low-productivity economy. Since its dramatic deindustrialisation in the 1980s, the country has lost manufacturing jobs much faster than its comparator economies. Manufacturing now makes up just 10 per cent of GDP, compared with 19 per cent in Germany and 16 per cent in Italy. The financial sector, Britain’s major export industry, continues to provide high salaries and skilled work. But the country’s once-lauded “flexible” labour market has proved a powerful driver of low productivity.

Fifteen per cent of the UK workforce is now self-employed, many of them contracted to just one client — a convenient way for the employer to avoid paying social security and providing holiday and sick leave and other employee benefits. Almost a million people are on “zero hours” contracts, with their working hours determined just a few days (or hours) in advance, and no level of work guaranteed. This has kept employment levels high — much higher than in other European economies. But it has also kept wages low, and given employers little incentive to invest in the skills or capital equipment that would raise productivity. Output per hour in Britain is around four-fifths of German and French levels.

Where Johnson is wrong is on immigration. Contrary to popular belief, there is no evidence that immigration reduces wages. Though it does mean a bigger labour supply, it also means higher demand (immigrants are also consumers) and therefore higher employment. The two effects largely cancel one another out. And, as Britain is now painfully discovering, immigrants do (or did) jobs that Britons simply don’t want to.

If his views on immigration are put to one side, Johnson’s criticism of the British economic model is much more usually heard on the left. This is, after all, a classic critique of modern capitalism: dominated by financial capital, more concerned to extract short-term profit than invest in long-term prosperity, seeking to pay workers as little as possible. And the solutions too come more naturally from the left: a stronger role for government in directing investment through active industrial policies; stronger trade unions to bargain wages up; reforms to corporate governance and finance to end the fixation with short-term returns.

Johnson didn’t propose any of these things, of course. His conference speech was almost entirely rhetoric, with virtually no policy content. But the implication of his remarks was not lost on the Conservatives’ ideological bedfellows. “Vacuous and economically illiterate,” railed the free-market think tank the Adam Smith Institute. “An agenda for levelling down to a centrally-planned, high-tax, low-productivity economy.” It would be fair to say that they didn’t like it.

And the reason is not hard to identify, for Johnson is confronting the legacy of the Conservatives’ great heroine, Margaret Thatcher. It was Thatcher who initiated the deindustrialisation of the British economy; who deregulated the financial sector and let foreign capital flow in freely to buy up Britain’s most valuable companies; who destroyed the power of the unions and created the flexible labour market. The British economic model is of the Tories’ own making, and if Johnson is serious about reforming it he will have to break decisively with the party’s free-market nostrums.

This is not just about raising Britain’s productivity and investment levels. All of Johnson’s stated priorities will require leftish policies. He has promised to reform the country’s poor-quality social care system — and has already raised income taxes to pay for it. He has pledged to “level up” Britain’s disadvantaged regions — which are more or less everywhere that isn’t London and the southeast of England. But that will require both higher public spending and more directed investment; he has already established a state-owned National Infrastructure Bank for the purpose.

He is also committed to tackling climate change, with a goal of achieving a 78 per cent reduction in emissions (on 1990 levels) by 2035 and “net zero” by 2050. That will require even more extensive regulation of the energy sector and industry, and public investment in energy efficiency and sustainable transport. None of these policies is comfortable territory for the post-Thatcher Conservative Party, and his critics on the right have not been slow to say so.

It is still possible for Johnson to differentiate himself from the Labour Party and the left. The new battleground is Britain’s version of the culture wars, in which the Conservatives cast themselves as the defenders of British nationhood and tradition against the “woke” metropolitan liberals who criticise the country’s colonial history and proclaim their multiple identities, none of them patriotic. This political dividing line, virulently reinforced by Britain’s largely conservative press, may work to bolster Tory support of a particular kind. But it doesn’t look like a strategy to win elections.

And this, in the end, is how Johnson’s foray into a new ideological positioning will surely be judged. If he can succeed in reviving the British economy with interventionist policies and higher taxes and spending after the pandemic — and if his plans to reform social care, reduce geographic inequalities and tackle climate change begin to look as if they might work — then the next election, due in 2023 or 2024, could vindicate his optimism. But if the coming months spiral downward into a Shakespearean winter of discontent, and the prime minister’s rhetoric proves to be as unhinged from reality as it looks to many today, then all Johnson will have proved is that he can wield words with boisterous skill.

But that has never been in doubt. It is on whether he can govern competently that the jury of British public opinion remains out. •