If a prime minister were “egged” today, it’s hard to imagine that the perpetrator would be let off with being arrested. But that’s what happened in November 1917 at Warwick Railway Station, 130 kilometres southwest of Brisbane, when a well-aimed egg knocked off prime minister Billy Hughes’s hat.

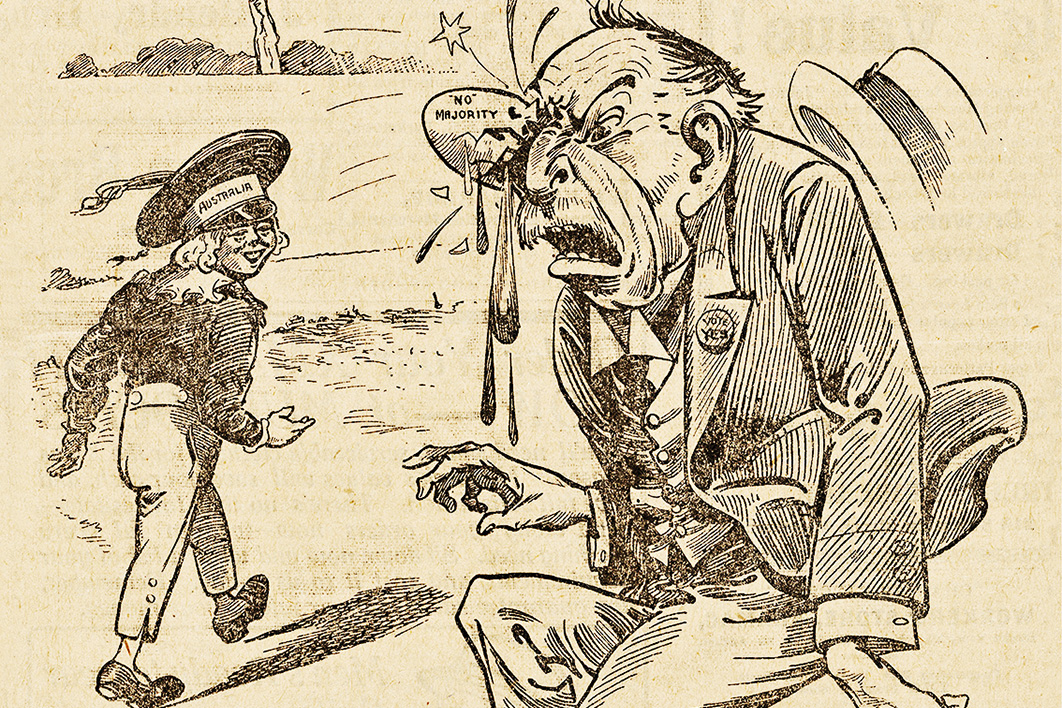

Since the Great War — the “war to end all wars” — had broken out three years earlier, conscription for overseas service had proved to be the most divisive issue among Australians. Hughes, a short, fiery Welsh-born former trade union leader, had been expelled by the Labor Party for arguing in favour. Along with twenty-three Labor supporters, he had joined the conservatives and retained the prime ministership.

Having lost the first conscription referendum as Labor leader, he now threw himself with gusto into a second campaign. Rotten eggs and unripe fruit were common missiles used by his assailants at increasingly rowdy public meetings, and Hughes took to carrying a pistol.

Queensland’s Labor premier, T.J. Ryan, a trade unionist and Irishman, despised Labor turncoats like Hughes. Ryan saw the war as yet another example of British imperialism, and became Hughes’s most vocal opponent. He told the Queensland parliament that the “conscriptionists” wanted to hand the “young democracy of Australia” to “capitalists” and “exploiters.” He attacked the federal government’s War Precautions Act as an attempt to “destroy unionism” and impose censorship. Hughes himself, often known for rash acts, took part in a raid on the Queensland government printing office in what proved a fruitless attempt to grab all copies of Ryan’s speech.

Two days later, on 29 November, Hughes set out to address pro-conscription rallies in Toowoomba and Warwick. When his train drew in at the elegant sandstone Warwick Railway Station, his supporters accompanied him to the platform. Sergeant Kenny, the senior Queensland police officer present, was standing by Hughes as he addressed the crowd when an egg struck the prime minister’s hat and another broke in front of him. Hughes demanded the arrest of the culprits, Irish-born brothers Bart and Pat Brosnan, and jumped down into the crowd when Pat gave him the finger.

Luckily for the brothers, who were well known to local police, Hughes had left his pistol on the train. The men were removed from the platform, with Bart bleeding heavily, having been punched in the face by Hughes supporters. Neither was arrested, though Pat spent a night in the lock-up before being released with a ten shilling fine for creating a disturbance.

The Warwick Egg Incident took just thirteen minutes, after which Hughes resumed his train journey to Sydney. At Wallangarra, he sent a telegram to the Queensland commissioner of police stating that Sergeant Kenny had refused to arrest the “two prominent ringleaders” for “a deliberate and violent breach” of Commonwealth law. Kenny told Hughes that “he recognised the laws of Queensland only.”

At subsequent rallies in New South Wales, Hughes embellished the Warwick Egg Incident, using it as evidence of the lengths to which supporters of the Queensland premier would go — even though eggs were often thrown at public meetings by both pro- and anti-conscriptionists. An official Queensland Police inquiry found that, apart from the egg, there had been no assault on Hughes. Hughes’s biographer, L.F. Fitzhardinge, concluded that Hughes was “well over the edge of hysteria, losing control of himself.”

On his return to Sydney, a furious Hughes portrayed both Premier Ryan and the Queensland Police Force as Sinn Feiners (members of the group opposed to the British rule of Ireland) and radical trade unionists, and promptly established a Commonwealth Police Force to offer personal protection to the prime minister and other ministers, and to protect federal property and ports, where left-wing wharfies were a powerful force.

Hughes lost the second conscription referendum just a fortnight later. The “no” majority had grown from 72,476 to 166,588 votes, and only two states, Western Australia and Tasmania, voted in favour, along with the federal territories.

The Warwick Egg Incident, well known in Queensland, is almost unheard of anywhere else in the nation. The incident is re-enacted on special occasions, with relatives of the Brosnan brothers in attendance. For many, it remains an amusing parable of a proud Queensland country town not succumbing to prime ministerial bullying.

It is also a reminder of an era when public meetings mattered, and politicians had to face the electorate, rather than hiding behind minders and security officers. While the railway station now only services freight, it is still possible to visit the site of this notable event in Australian history, the catalyst for the creation of what is now called the Australian Federal Police. •

This is an edited extract from Where History Happened: The Hidden Past of Australia’s Towns and Places, by Peter Spearritt (NLA Publishing, $39.99).