“Love is a creature of its time,” writes Alecia Simmonds. “And it is in the space between strangeness and familiarity that the history of love can be found.” Simmonds is mistress of the well-turned phrase and the arresting observation. She is also a fine historian. In her elegantly written new book, Courting: An Intimate History of Love and the Law, she interrogates the strange and the familiar to illustrate love’s history in Australia and its long entanglement with law.

Her sources are “the papery remains of blighted affection,” the records of the 1000 or so cases involving alleged breaches of promises to marry that were brought before Australian courts between 1788 and 1976. These papery remains are brought to vivid life by her broader research — in archives, museum collections, newspapers, memoirs and genealogies — into the lives of the women and men who were at the centre of these cases. As she promises, she writes “a peopled history, one in which the reader gets an insight into the inner lives of women and men in the past, a feel for the textures, sounds and smells of the world which they inhabited.”

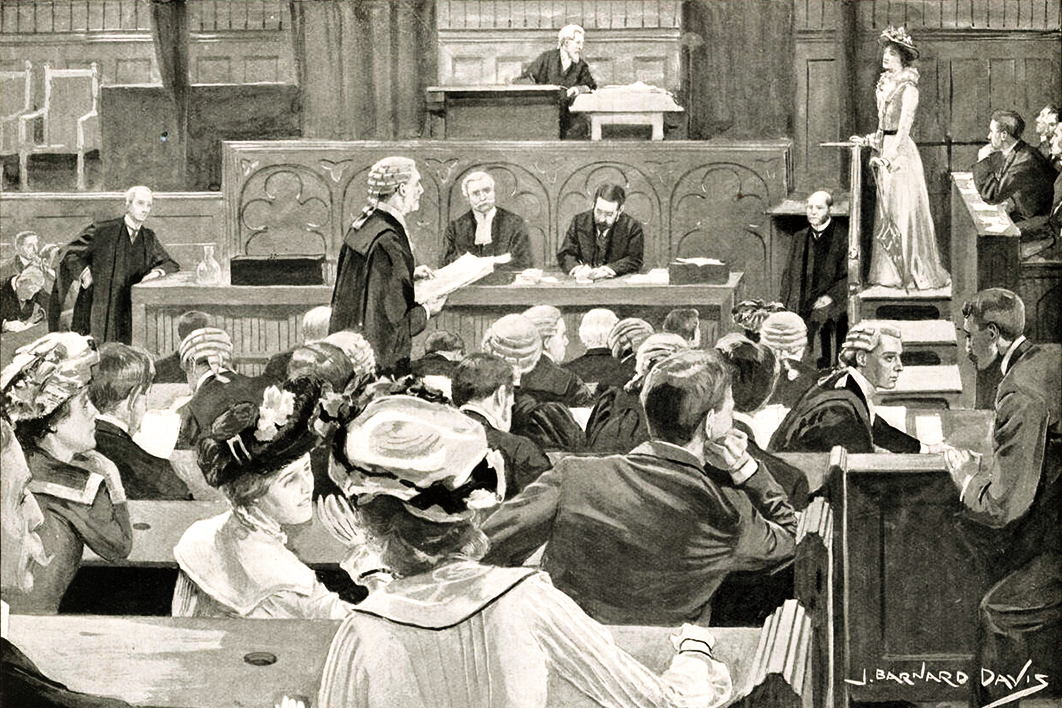

Courting is organised around eleven case studies, in the full sense of the term: eleven breach-of-promise cases divided into four time slots, each focused on a period of change. Her choice of cases is shaped by the themes she wishes to investigate: the use of marriage to civilise the convict colony, when law and love were entangled; the geography of mid-Victorian courting, when bourgeois scripts were not always followed; the social turmoil of turn-of-the-century Australia, most strikingly in terms of racial politics; and the commodification of love in a psychologised, therapeutic society, when law and love went their separate ways.

Along the way the reader meets some fascinating people. Outstanding for me was Sarah Cox, “young, feisty, and possessed of ‘killing beauties,’” a seamstress who in 1825 successfully sued a lover for breach of promise but was then disgraced by bearing an illegitimate daughter fathered by her lawyer. That she later married the lawyer and became Mrs William Charles Wentworth did nothing to restore her to Sydney society.

Though her daughter Timmie married well, Sarah was banned from any contact with her other than by letter. When William died in 1872 she wrote to Timmie: “The light of our dwelling has left us so desolate for he was the one that made our house so very cheerful.”

Then there was James Lucas/Jamesetjee Sorabjee, a South Indian merchant from Hong Kong who won his breach-of-promise case in Sydney in 1892. Simmonds’s research makes Lucas an understandable, sympathetic figure: he was a Parsi, and therefore “raised among people who delighted in going to court.”

In 1916 there was schoolteacher and “flighty flapper” Verona Rodriguez, who claimed £5000 for breach of promise, including £180 for her trousseau, and lost the case. Simmonds take us into the warehouse of the Powerhouse Museum to finger with her “the buttery softness” of silk nightdresses from trousseaux of the period so we can imagine the salacious scene in the courthouse when Miss Rodriguez’s nighties were produced as evidence. This is intimate history indeed.

Together with this close reading of the past, Simmonds offers some broad-reaching readings of historical change. She delights in challenging established truths — those established by historians and those assumed by experts and activists in the past and the present. Lawyers and psychologists, feminists and defenders of human rights — all will find their preconceptions under challenge in this ambitious volume.

Simmonds teaches law at the University of Technology, Sydney, and law students and professionals are one of her intended audiences. The backstory to her trail of breach-of-promise cases tells of an evolving legal practice and profession that became more abstracted over time from ordinary reality. In the earliest years “ordinary people” used the common law as “a set of ancient rights and inherited privileges” and “as successful stories became binding precedents, common people, as much as judges and legislators, made law.” By the end of the nineteenth century civil law was turning away from torts to contract law, privileging material evidence (like nightdresses) and bureaucratic logic. And today, says Simmonds, we live with a “divided legal system” in which the poor “are channelled into the criminal law while the wealthy have the comfort of the civil courts.”

Simmonds’s litigants are not wealthy, and mostly not very respectable, for “working-class people… were the people who went to court.” As a corrective to bourgeois scholarship, she draws on their voices to argue that the rules of nineteenth-century working-class courtship were different from those of middle-class courtship. Women in paid employment were never limited to the private sphere like their middle-class employers, and “they also had more sex.” Sex before marriage was perfectly acceptable so long as marriage followed. Simmonds writes with cheerful bias that the “countervailing working-class romantic culture… was delightfully resistant to respectable mores.”

But Simmonds’s corrective goes further. American and British histories of love mark the 1890s as the period of greatest change, the time when women moved into the public sphere and capitalism moved courtship out of the home. But “Australia tells a different story,” says Simmonds. Capitalist prosperity came early to Australia, and by 1880 Australian city environments were “based more on pleasure than prohibition,” offering cost-free romantic opportunities to lovers of all classes:

Far from being a classic tale of embourgeoisement — of the working classes becoming respectable — what we see by the 1880s is the middle classes gradually taking up more expansive working-class romantic geographies.

Perhaps this reading would apply to all industrialising, city-building societies at the time.

Simmonds’s reading of the decline and eventual abolition of the breach-of-promise action denies — or at least sharply modifies — the understandings of the feminists and equal rights advocates who consigned it to legal oblivion in 1976. Second-wave feminism’s focus on making women economically independent made them understand breach of promise as reactionary, forcing women “back into dependency on men and marriage.” Simmonds recognises that its abolition marked an advance in women’s status, but she is more concerned with what was lost.

Her revision is based on an understanding of common law as privileging a public language of “moral norms and economic responsibility.” Within this frame the action of breach of promise “produced feminist political subjects.” This seems a large claim, and it is based here on the evidence of a single case study.

But Simmonds’s structural analysis is compelling. Breach of promise required women to take a public stage, to stand in judgement of men, to take their own feelings seriously. The action “elevated private pain to a question of public justice,” and “put a price on the unremunerated feminine labours of love.” Its abolition marked the loss of “compensation for psychic and economic injury” and “the individualism of emotional harm.” It was not “the triumph of love over sexist tradition” but “the final chapter in a story of how love… lost many of its ethical and material foundations.”

This is a radical rewriting of legal and emotional history. It will be fascinating to see how historians currently researching these fields choose to engage with it. •

Courting: An Intimate History of Love and the Law

By Alecia Simmonds | La Trobe University Press/Black Inc. | $45 | 448 pages