Few observers thought the water polo match between Hungary and the Soviet Union on 6 December 1956 would become so violent. The timing was important: the match occurred only days after ninety refugees fleeing the Soviet crackdown in Hungary had arrived in Australia. That alone would have brought reminders of home, and increased the intensity of feeling among the Hungarians. It was a spiteful and nasty contest, which Hungary — the defending Olympic champions — won by four goals to one. And a “blood in the water” moment gave it a heightened sense of drama and intrigue.

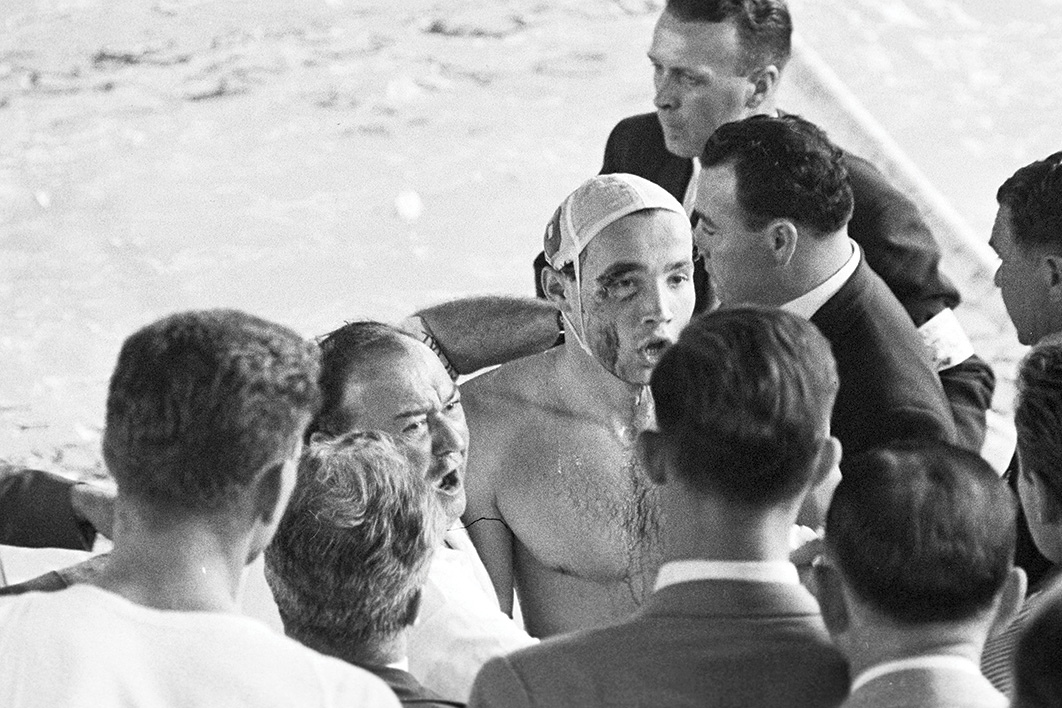

A Hungarian player, Ervin Zádor, was punched off the ball by a Soviet opponent, and left the pool with blood streaming down his face. The Hungarians claimed they had been instructed to avoid physical confrontation, and that the Soviets had made offensive remarks during the match. “We were told we must win, but don’t fight, don’t box and don’t play rough,” Hungarian captain Dezső Gyarmati said afterwards. The crowd at the Olympic pool quickly identified who they thought were the sinners and the sinned against, cheering the Hungarians and booing the Soviets when they left the pool at the end of the game.

Those who weren’t at the pool but had access to a television would have seen for themselves what was going on. All three networks — the ABC, HSV-7 and GTV-9 — were there to record the match, but only GTV-9 had compelling footage of what was happening under the water. “We had put all our cameras in the hands of our fledgling producers and one of the most enterprising of them discovered there were glass portholes on the sides of the Olympic swimming pool,” the station’s managing director, Colin Bednall, explained. “We secretly put a camera lens to one of the portholes.”

The lens revealed just how hard the Hungarians worked to provoke their Soviet opponents. “Those parts of the body the Hungarians worked on were well below the surface of the water,” Bednall pointed out. Hungary went on to win the gold medal, and the team was roundly cheered at an emotional medal ceremony.

Before the Soviets had cracked down in Budapest, the Hungarian capital had been in the grip of rising anti-Soviet feeling, driven by a suspicion that Moscow was taking advantage of its smaller ally, especially by paying bargain prices for the country’s uranium. A poor harvest and shortages of fuel were driving discontent and disillusionment, and the presence of Soviet troops was a constant reminder of Russian oppression. In neighbouring Poland a new leader, Władysław Gomułka, was promising to distance his country from Soviet control. Some Hungarians hoped their nation would take a similar path.

Students had gathered in Budapest in October and endorsed a sixteen-point plan that demanded major economic reforms, restoration of free speech, free multi-party elections, total equality in relations between Hungary and the Soviet Union, and the removal of all Soviet troops. On 23 October more than 200,000 protesters marched on the parliament, and later in the evening toppled the huge bronze statue of Stalin that had been erected in 1951.

How the Canberra Times reported the polo match in its 7 December 1956 edition. Trove

An attempt by the insurgents to capture the radio station so that it would broadcast the sixteen points turned ugly, and as night became dawn a battle between the secret police and the revolutionaries left twenty-one people dead. The government fell, and a new administration under the liberal Imre Nagy emerged. For several days, comparative calm prevailed, with initial agreement from Moscow for this new regime to exist within the Soviet orbit. But reality was about to show otherwise.

Some members of the Hungarian Olympic team in Budapest were alarmed and profoundly moved by what had happened. The uprising’s practical consequence for the Olympic team was that the two French planes chartered to take them to Australia could not land at the Soviet-controlled airfield in the capital. The planes went to Prague instead, and the team members had to find their way there. The Hungarians climbed aboard five buses that took them to Bratislava; from there they took a train to Nymburk, not far from Prague.

Once there, they held a team meeting to discuss what they should do. Some of the athletes thought the revolutionaries had finally seen off the Soviet troops, and they should go to Melbourne under the new Hungarian flag that the students had carried in Budapest. There was no doubt, the team decided after a vote, that they should continue on to Melbourne. But in the five days it took the two French planes to get to Melbourne, the situation in Budapest deteriorated.

By the time the Hungarian Olympic team arrived in Australia, the Soviet army had re-established bloody control of the city. The Nagy government had been overthrown, and 200,000 Soviet troops had swept into Hungary. The death toll was a grim reminder of Moscow’s determination to snuff out any signs of resistance.

Four Dutch athletes, an official and a coach were already in Melbourne when their country’s national Olympic committee sent a telegram: “At extraordinary meeting the Dutch Olympic participation to withdraw due to Hungary. Leave Olympic Village. Find other place to stay. Wear civilian clothes — if impossible remove [national Olympic] badge… Cancel all hotel reservations but reserve Hotel Windsor… Sorry all the best.” It was a sudden end to the Dutch athletes’ dreams. Some were in tears, but there was no doubt about their nation’s motives for their withdrawal: to emphasise the point, it donated 100,000 guilders to the victims of the violence in Hungary.

The Swiss, legendarily neutral, had a harder time reaching a decision. To send its team to Melbourne, the country’s Olympic committee required unanimous support from its national sports federations, but that wasn’t forthcoming after the events in Hungary, so the Swiss decided not to attend. The country’s most senior Olympic official, Otto Mayer, was the International Olympic Committee chancellor; he called the withdrawal a “disgrace.” Although the Swiss changed their minds, it was too late to send the whole team.

Five Nordic countries — Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden — prevaricated, eventually agreeing to compete nine days before the opening. A “new” team was also on its way — a united German team, which meant both East and West Germany would compete under a common flag and uniform. Spain pulled out in solidarity with Hungary, implying that it didn’t relish the prospect of fraternising with communists.

The world was watching: international photographers capturing the Games. Keystone Press/Alamy

Then came the big one: Communist China pulled out too, because the Republic of China — known at one time as Formosa, and now generally known as Taiwan — was competing. The official government mouthpiece in Beijing stated: “This artificial splitting of China cannot be tolerated.” It had stressed that only one China could be recognised at Olympic level, and it was not Chiang Kai-shek’s little domain. Formosa, according to Beijing, was no more than a province of China. And the circumstances on the ground revealed how a low-level mistake could feed into a high-level diplomatic stand-off.

At the official opening of the Olympic Village the Australian army corporal in charge of the national flags was approached by a Chinese journalist and told that he was preparing the wrong flag for the Republic of China. Taking this in good faith, the corporal went off and returned with another Chinese flag — that of Communist China. When it was hoisted on the flagpole allocated to Formosa, all kinds of hell broke loose within the Formosan team. “It’s inexcusable,” exclaimed one member. “We will protest.” The contrite corporal admitted his ignorance: “I didn’t know the difference in the flags, but I certainly do now.”

The correct flag was reinstated, but not without offending a mainland Chinese journalist, who confronted organising committee chairman Wilfrid Kent Hughes because he was insulted by his country’s flag being taken down. Kent Hughes had just finished apologising to the Republic of China representative and now found himself trying to placate the other China. He told the journalist that the Communist China flag would be raised when the team arrived in the village. When the discussion continued, Kent Hughes told the journalist he was too busy to continue the discussion but was happy to resume it the next day.

“This is a free country and I am entitled to talk to you,” the Chinese journalist said.

“Yes, it’s so free I don’t have to listen to you,” Kent Hughes replied, and walked off.

The next day Communist China announced it would not be taking part in the Melbourne Olympics.

That made seven nations no longer coming to Melbourne. None of it had anything to do with how far away Australia was from Europe or Asia. It had little to do with the calibre of the competition, the weather, the time of year the Games were held, or the cost. It was about the cold war and international sensitivities. Melbourne became the first Olympic Games affected by international boycotts.

How Melbourne would respond to the Soviet Union’s participation was set well before Suez or Hungary, when the Melbourne organising committee made it clear that no Iron Curtain countries would be given special protection. The committee’s chief executive, William Bridgeford, told the international press that Australia had made it clear to the Russians that they would be treated just like everyone else in Melbourne. “We couldn’t segregate them if we wanted to,” he said. “The Olympic Village is the only place where we can house and feed the athletes.”

The statement was a sensible and practical response to the anxiety surrounding the biggest bear in the cold war woods. No one had the time or inclination to do the Russians any favours. The events in Hungary only confirmed that treating the Russian athletes like every other athlete was the best policy.

That wouldn’t prevent one arm of the Australian government having special plans for them. ASIO had been preparing for the Games for more than twelve months. It was well aware of the potential dangers of having so many communists in the country at the one time. The fallout from Suez and Hungary, although never part of ASIO’s original planning, added another layer of complexity to the task.

ASIO believed it needed to monitor for three possibilities. One was that communist agents might use the Games as cover for their own intelligence operations. Another was the potential assassination threat to former diplomats Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov in retaliation for their defection to Australia two years earlier. The couple were moved to a safe house in Queensland for the duration of the Games, just to make sure they were out of the way. And the third concern was the possibility of athletes and officials seeking political asylum, a likelihood that increased in the aftermath of the Hungarian uprising.

After liaising with the Department of External Affairs and several others, ASIO got cabinet approval to establish a process for dealing with potential defectors or “refugees.” A safe house and flat were set up in Victoria — other states were told to have a similar arrangement in place in case it were needed — and ASIO officers were put on rosters to ensure there was always someone available to activate the plans.

The Hungarian community in Melbourne had been following the events back home closely, and turned out in force at Melbourne’s Essendon airport to meet the team when it arrived on the evening of 12 November. Joseph Csonka, the head of the local Hungarian Association, declared that he and others would ask every Hungarian on the team if they intended to stay in Australia. If they said yes, he would submit their names to the government to be considered for political asylum.

The Argus didn’t care for such messages at all, declaring in an editorial that Csonka had “dismayed” Melbourne. “It is dangerous impertinence for Dr Csonka — speaking for people who themselves are guests of Australia — to provoke a political explosion that could so deeply embarrass us,” thundered the paper. “It’s plain bad manners for him to try to set friend against friend in the Hungarian team — and incite angry hostility against other competitors who are also our guests… SO STAY AWAY FROM OUR VISITORS, DR CSONKA AND FRIENDS.”

The message revealed a superficial understanding of what exactly had happened in Hungary, and underlined a naive view that overseas politics was something you declared at Australian immigration control and surrendered at the gate. At Olympic Village, the communist flag of Hungary had been replaced by a new flag, one ordered by the Nagy government. At the airport the gathered Hungarians sang the old national anthem that had existed before the communists, and tears were shed. In Canberra the prime minister pledged Australia would take 3000 Hungarian refugees.

When the planes carrying Hungarian refugees landed three weeks later, the ninety men, women and children on board were just the first of those whom Australia was committed to housing — and there was growing evidence that 3000 would not be enough. The United States announced it was boosting its original figure of 5500 refugees to 21,500. The new Soviet-backed Hungarian government was vigilant at its border with Austria, and reports emerged of between 1800 and 2000 people being caught at the border every day and taken to Hungarian camps.

The members of the group that landed at Mascot airport on the morning of 3 December all had stories to tell. One couple was reunited after having been separated for eight years — the man had stayed in Budapest getting ready to join his wife in Melbourne, but it took the uprising to sweep away all the barriers to their reunion. A diminutive resistance fighter named Ferenc Ritter, who was married to a double-bass player in a Hungarian orchestra, hid in his double-bass case to ensure they crossed the border into Austria safely.

For Professor Islvan Pavlovitz, there was also the incentive of coming to a country where barracking at a football match was allowed. The professor of bacteriology at Budapest Technical University had been arrested, put in jail, and dismissed from his university post for barracking too loudly in support of a Hungarian soccer team playing a visiting Soviet side. When he was talking to Australian immigration officials in Vienna, the professor asked the question: “Is barracking at football matches banned or restricted in Australia?” When he was told that barracking was fine, Pavlovitz decided Australia was for him.

The United Nations deputy high commissioner for refugees, John Read, outlined the extent of the humanitarian challenge: 92,000 Hungarians had arriv-ed in Austria after the uprising, but as of the start of December, only 22,000 could be accommodated in new homes around the world. What was to become of the other 70,000? Two days after the first group of Hungarians arrived in Australia, the government announced it would take another 2000 under assisted passage agreements. More would need to follow them.

Just as ASIO director-general Charles Spry had anticipated, a sizeable number of Hungarian athletes didn’t want to go home. Hungarian officials had been coy in the build-up to the Games about whether there would be any defections, but it became clear as the Games went on that discussions were taking place among the team members and with local supporters who were prepared to help some athletes stay. In line with Spry’s advice, the Hungarians received no encouragement from Australian officials or government representatives to defect. The entreaties fell on deaf ears.

At the end of the Games, sixty-one athletes and officials, including forty-eight Hungarians, refused to return home. Many of the Hungarians travelled to the United States on what was billed “the Freedom Tour,” underwritten by magazine Sports Illustrated, which was owned by the fervent anti-communist Henry Luce. Only six Hungarian team members — including steeplechase silver medallist Sándor Rozsnyói, wrestler Bálint Galántai, kayaker Zoltán Szigeti, and sprinter Géza Varasdi — stayed in Melbourne. •

This is an edited extract from Nick Richardson’s 1956: The Year Australia Welcomed the World, published by Scribe.