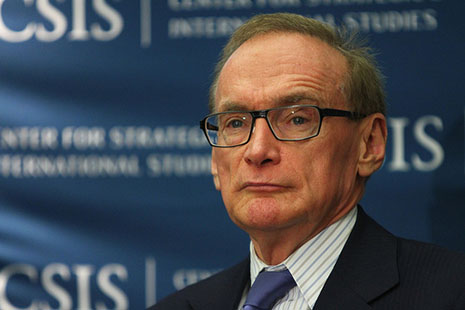

WHEN foreign minister Bob Carr calls for “a tougher, more hard-edged assessment” of refugee applications he sounds remarkably like former immigration minister Philip Ruddock.

Speaking on ABC1’s Lateline, in the Senate, and on ABC Radio’s AM, Senator Carr argued that we need tighter refugee determination procedures because the flow of asylum seekers to Australia by boat has changed in two fundamental ways. First, “100 per cent” of asylum seekers travelling by sea are being brought here by people smugglers. They haven’t “cobbled together, in their desperation, money to buy a fishing trawler and set out onto the high seas”; they are people “captured by money-making criminal syndicates.” Second, he said, “these are increasingly not people fleeing persecution.”

Rather than indicating any sharp break with the past, what these comments underline is just how little has changed, particularly in the rhetoric of federal government ministers.

Since the late 1970s, the majority of maritime asylum seekers have relied on people smugglers to organise their journeys. Over and over again, however, the payment of money to criminal syndicates has been used to denigrate asylum seekers and to cast doubt on their claims for protection. Compare Senator Carr’s words to those of Philip Ruddock, the Coalition immigration minister from 1996 to 2001, who once described “boat people” as “those who have the money, those who are prepared to break our law, those who are prepared to deal with people smugglers and criminals.”

On Lateline, Senator Carr also questioned the legitimacy of recently arrived Iranian asylum seekers because they are “middle class.” Again, it’s a familiar refrain: Philip Ruddock used to speak disparagingly of “so-called boat people… flying first class into Indonesia and Malaysia before boarding rickety vessels for Australia.” It need hardly be said that individuals can suffer persecution regardless of their socioeconomic status. Dictators don’t hold back from torturing political dissidents because they are “middle class”; religious autocrats don’t exempt homosexuals from jail because they come from a good family.

Not that being poor would win an asylum seeker any greater legitimacy in the eyes of government than being well-off does. If the majority of people arriving by boat were landless peasants or unemployed labourers, we can safely assume that government ministers – Labor or Coalition – would accuse them of coming to Australia in search of a better job rather than to escape from persecution.

Senator Carr also questions whether people from “majority religious or ethnic groups” – Shia Muslims from Iran or ethnic Sinhalese from Sri Lanka, for example – can be refugees. Again, it should be obvious that people can be persecuted for a wide range of reasons, irrespective of their cultural background or faith.

AT THE heart of Bob Carr and Philip Ruddock’s arguments is a belief that Australia’s refugee determination procedures are overly generous – that they fail to separate out the pure grain of refugees from the undeserving chaff of “economic migrants.”

Bob Carr told Lateline’s Tony Jones that when asylum seekers arriving by boat are being granted protection under the Refugee Convention at a rate of nine out of every ten then the assessments are obviously “coming up wrong.” He said this situation had arisen “as a result of court and tribunal decisions.”

It sounds familiar. When I interviewed Philip Ruddock for my book Borderline in 2000, he used the same argument. Australia was dealing with a flow of people with “non–bona fide claims,” he said, and yet their applications for protection from persecution were “generally upheld.” Over time, he said “a judicial gloss” had developed in Australia, and as a result the Convention was interpreted more broadly than in other countries.

Just how true is this?

It is always difficult to make direct comparisons between refugee determination procedures in different countries with different legal systems, but the most recent figures from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees suggest that Australia’s asylum record is entirely unremarkable.

The UNHCR Statistical Year Book 2011 lists the outcome of refugee applications in each country of asylum. It shows that 42 per cent of the asylum seekers who sought refugee status in Australia during 2011 were granted protection (by immigration department officials) in the first instance. When some of the rejected applicants sought a review at the Refugee Review Tribunal, 30 per cent were recognised as refugees.

These numbers are much lower than the 90 per cent approval rates commonly cited for maritime arrivals because they also include asylum seekers who arrive by plane on valid visas and then seek protection. “Plane people” are rejected at much higher rates than “boat people.”

If the decisions made at the primary and appeal stages are combined, then in 2011 Australia granted protection in 39 per cent of cases. In global terms, this puts Australia close to the average: the UNHCR estimates that, worldwide, 38 per cent of asylum seekers who had their cases determined in 2011 were granted refugee status or some other form of protection. According to the UNHCR data, Australia granted protection to a significantly smaller proportion of asylum seekers than Finland (67 per cent) but a much larger proportion of asylum seekers than Italy (20 per cent). Australia’s refugee recognition rate was broadly comparable to that of Canada, Britain, Spain and Sweden.

Nor does it appear that Australia is overly generous to asylum seekers from specific countries. The UNHCR Statistical Year Book breaks down refugee status determinations by country of origin and territory of asylum. It shows that 57 per cent of Afghan asylum seekers in Australia were granted protection in 2011. A higher proportion of Afghan asylum seekers were granted protection in Indonesia (97 per cent), Canada (89 per cent) and Austria (68 per cent), and a lower proportion in France (38 per cent) and Denmark (20 per cent). Overall, Australia came out just a bit above the global average of 50 per cent.

As the table shows, the proportions of Iraqi and Iranian asylum seekers granted protection in Australia were also close to the global average. Protection rates were higher for asylum seekers from Sri Lanka and stateless people, and lower for asylum seekers from China.

Refugee approvals by source and destination countries

Source country Percentage granted protection in Australia Percentage granted protection globallyAfghanistan5750China1852Iraq6562Iran5855Sri Lanka5326Stateless5937All source countries3938

Source: UNHCR Statistical Year Book 2011, Statistical Annex, Tables 11 and 12

Clearly, not everyone who seeks protection in Australia is a refugee under the Convention. Like other nations, we must deal with the reality of mixed flows. People move across borders for a wide range of reasons, some political, some cultural, some religious, some economic. Often these motivations exist simultaneously in the same person: a Tamil couple who fear abuse at the hands of the Sri Lankan government might also hope that Australia will offer their children a better education and a brighter economic future.

No refugee status determination process will be perfect. Inevitably there will be situations where people with marginal, even fraudulent, claims are granted refugee status; others will be turned down because their stories don’t convince authorities, even though their case for protection is strong. So far, however, neither Bob Carr nor Philip Ruddock has managed to produce convincing evidence that Australia’s refugee assessment process is flawed or overly generous.

In fact, in one area of refugee protection Australia has generally proved far tougher than most other developed nations. In other countries, failed asylum seekers often disappear into the general population; in Australia, with its universal visa processing and well-developed compliance system, few undocumented migrants manage to avoid detection and removal for very long.

So if Bob Carr really believes that most of the asylum seekers now arriving by boat are “economic migrants” then he should feel confident that the scale of Australia’s refugee “problem” will soon diminish. As we have seen in the past, with the arrival of people from Vietnam, Cambodia and China, once the flow of people with legitimate claims to protection diminishes, a greater proportion of applicants are refused a refugee visa and returned home. This has the effect of discouraging other compatriots from making the same dangerous journey, unless they have very compelling reasons to do so.

As Philip Ruddock once told me, “there is nothing more galling to a people smuggler than to find his clients back, unsuccessful.” When that happens, he said, the smuggling stops. If the foreign minister is confident in his assessment that many recently arrived asylum seekers are really economic migrants, then he should let the refugee determination system do its work. •