Sometimes in the depths of winter, when I consider trudging through a cutting wind and the promise of sleet to a strenuous fifty-minute session on the machines for muscular improvement invented by Joseph Pilates more or less a century ago, I remind myself that the legendary movement teacher was famous for wearing tight black shorts and canvas slippers — and nothing else — not only at the Manhattan studio in Hell’s Kitchen where he taught for so many years but outdoors as well, no matter the weather, on his daily jogs around the neighbourhood. And remembering this I tell myself that if he could venture into even New York’s worst blizzards in tiny shorts, then I certainly can bundle up and get myself to a Pilates session, knowing that after a stint on the Reformer, followed by the Cadillac and an occasional ten minutes on the Barrel or even the dreaded Chair, I will emerge a physically and morally improved human being.

Pilates died in 1967, and I am grateful to have missed the opportunity to train with the master. There was the showering thing, for example: according to John Howard Steel, a devoted pupil who wrote a fair-minded and helpful book about him, Caged Lion, Joe (everyone called him Joe) insisted that immediately after a session students leap into a cold shower, where he would occasionally make an unannounced appearance, scrubbing them down vigorously, front and back, with a stiff brush. There was, in the studio, his prim, unsmiling wife, Clara, dressed in a white nurse-like uniform. There were the endlessly repeated stories he told about his youth in Germany as a boxer and his years in an internment camp for German nationals in northern England, where he devised his machines using springs from the beds for inmates with tuberculosis and other diseases — stories that are hard to prove but that some of his followers stand by.

A compulsive self-mythologiser, Pilates said he was born in 1880, though he was actually three years younger. He said he had developed his technique in order to help wounded soldiers in the first world war. There is no evidence that this is so. He said he was of Greek background, a direct descendant of Pontius Pilate, and a victim of bullying because of that traitorous origin. Again, some of his most devoted followers have tried and failed to find the evidence for this, as we learn in books like Hubertus Joseph Pilates by an obsessive Spanish couple, Javier Pérez Pont and Esperanza Aparicio Romero. Pilates trainers themselves, they treat us to the untos and begats not only of the Pilates family but of Joe’s in-laws and even several of his collaborators, all the way back to the seventeenth century.

Pérez Pont and Aparicio Romero give us a meticulous description of an English internment camp for Germans during the first world war, only to learn that it is not the camp where Pilates spent four and a half years. There’s a technical description of a tank, even though he was never a soldier, and so forth. And it’s no use skipping around in the book, because buried somewhere in that mass of facts we find the date of his marriage to his first wife and entire chapters of useful and carefully sourced information.

According to Pérez Pont and Aparicio Romero, Hubertus Joseph Pilates was born into a typical German working-class family in the small town of Mönchengladbach. His father was a locksmith, his mother a housewife. The family moved from apartment to apartment, always in the same neighbourhood, whenever they were unable to scratch up enough money for the rent. The elder Pilates obtained a membership at the local turnverein, or community health club — a great German invention — and soon his firstborn son, who was weakly and asthmatic, was training compulsively there. Josef, as he liked to call himself until he immigrated to the United States, worked for some time as a brewer in the local beer factory. He married, had a child, became a widower, married again and had another child, and displayed a strange ability to move between worlds.

In 1913 or so, looking for opportunity and sensing his country’s gradual collapse into war, he moved to London. It would appear that he did some boxing there and also performed what was then a popular circus act, dusting himself with flour and striking “Greek poses” to show off his muscled physique. This adventure lasted six months. He spent the war years on the Isle of Man in an overcrowded and sordid internment camp.

Pilates may or may not have saved thousands of his fellow prisoners from the Spanish flu, as he claimed. Pérez Pont and Aparicio Romero point out that the absence of flu in the camp was more likely owing to its remoteness. There is no question, though, that Pilates was already thinking about machine-aided exercise during that time. Back in Germany after the war he tried to find success, first in staged boxing exhibitions and then as a match promoter. Simultaneously he started identifying himself as a Heilkundiger, which Pérez Pont and Aparicio Romero translate as an “expert in the science of natural healing,” and he landed a job as a physical education instructor with the Hanover police.

Meanwhile, he was busy designing strange little apparatuses — a metal hoop with inner leather rests for the hands or feet that he called a Magic Circle; the Wunda Chair, with a pedal supported by springs; the Reformer, a movable bed, or platform, attached by means of leather straps to a low steel frame — and applying for patents for each one in Germany and then in the United States, Great Britain, and France. According to Pérez Pont and Aparicio Romero, the choreographer and movement notator Rudolf Laban came to his studio and was impressed. So was the avant-garde choreographer Mary Wigman, maybe.

Pilates saved a little money and travelled to the United States, where he visited a brother and an uncle who had immigrated to Nebraska. In the mid-1920s, when it was clear to him that Germany was headed for a second economic and political collapse, he left behind his German life — wife, children, police academy gig, arty connections — and boarded a ship to New York. Mid-Atlantic he met a frail nurse named Clara, who became his helpmeet and lifelong companion. They had no children, but for a few years one of his nieces, Mary, came to New York and trained with him.

He landed in New York in 1926, no longer a young man, armed with only a prestigious but very small reputation back in his native Germany as an unusually creative physiotherapist. Squarely built, not tall, blue-eyed — his right eye was slightly crossed and sightless — he was by most accounts neither socially graceful nor articulate. He was possessed, though, of a lifelong boundless faith in himself and in the machines he began to build with his stateside brother to his own exacting specifications. He was convinced that his machines, exercises, and principles of Healthy Living and Good Hygiene would help the United States fulfill its promise of greatness and make him world-famous in the bargain.

It was sheer luck that an obscure trainer from interwar Germany happened to share the great American obsession with healthy living and good hygiene at just the right moment. There were already many insane diets, health foods (Corn Flakes!), gut regulators (Grape-Nuts!), and laxatives (enemas!) on the market, and breathing techniques and exercises and machines not unlike the Reformer and the Wunda Chair that were in use back in the turnvereins of Joe’s youth. (German immigrants to the Midwest brought the turnvereins with them, and they evolved into America’s first health clubs.) The loopy Bernarr Macfadden, the founder of Physical Culture magazine and proponent of the starvation diet, had been wildly successful for a time. A Macfadden protégé, bodybuilder and all-American he-man, Charles Atlas (born Angelo Siciliano), was Joe’s contemporary. Unlike them, Pilates offered both a radical innovation — the machines — and his uncanny, intuitive understanding of muscles and how they work.

The first studio where Joe offered training using his patented machines in what he always called Contrology was open by 1934 in Hell’s Kitchen. The years following his arrival in New York must have been tough, what with the Great Depression and his lack of English. Yet the studio’s dodgy neighbourhood turned out to be perfect: several dance companies would eventually have their studios nearby, notably George Balanchine and Lincoln Kirstein’s fledgling group, Ballet Society, which was adopted by City Center as a resident company; Lincoln Center would later rise a few blocks away. The rent was cheap; the space was large. The studio must have come as a great relief, both a grounding and the beginning of the dream; he and Clara moved down the hall and lived there until the day he died. Love All Around, a biography of his most important disciple, Romana Kryzanowska, describes Joe, a cigar in one hand, a glass of whiskey in the other (healthy living indeed!), coaching new students while demure Clara kept a perceptive eye on the rest.

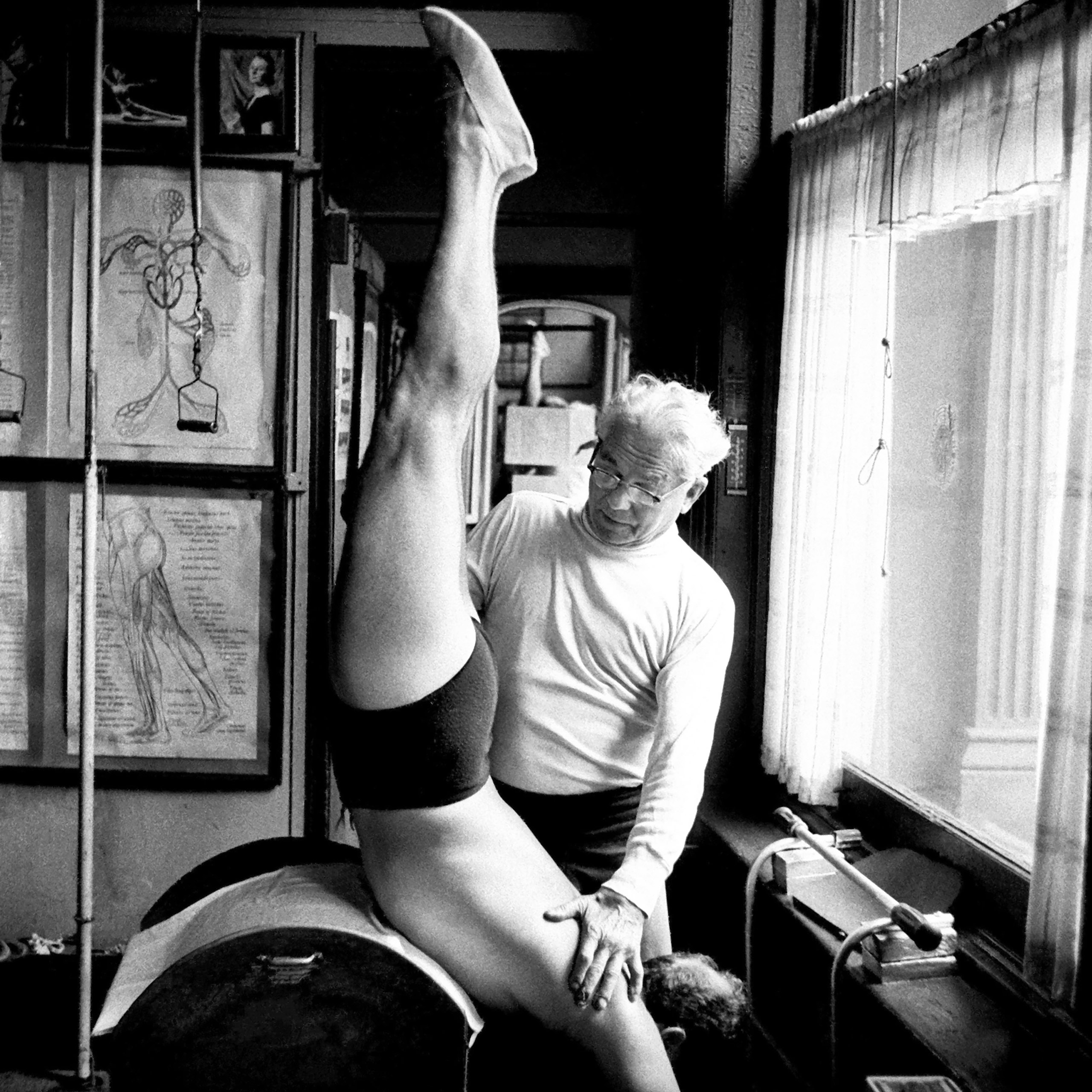

Kryzanowska was an aspiring ballet dancer of Polish, Ukrainian and Quaker descent who was cursed with weak ankles. Balanchine (who used to train occasionally at Joe’s studio and never had to sign in) sent her to Joe to see what he could do. “Always people touch their toes,” the brilliant dancer Allegra Kent quotes the great Russian choreographer as saying. “But Joe is more serious, more intense. He understands human body.” On her first visit, Kryzanowska walked into a crowded room filled with hairy, sweaty men working out on the bizarre machines and met Joe, who was wearing his usual skintight shorts, chatting, and making occasional corrections. There were Oriental rugs on the floor and plants on the windowsills and, on one long wall, framed photos of Joe, letters of endorsement, and anatomy charts.

Kryzanowska proved to be an unusually perceptive and receptive student, and she spent many months training under Joe’s enthusiastic supervision, eventually teaching classes at his studio under his guidance. She left ballet, and Joe’s studio, when she met and married a wealthy Peruvian businessman and went to live with him for a few years in Lima. Following the master’s death decades later, several of his well-off devotees provided the financial backing and encouragement for the studio to continue under her direction. Kryzanowska went on to become the teacher most responsible for ensuring that Joe’s machines, his technique, and his great discoveries about the human body all survived him.

The studio prospered for decades, but that was never Joe’s ultimate goal. Late in life he went on a fruitless campaign to contact President Kennedy or his wife: he wanted Pilates conditioning to be taught in public schools. He never got an answer from the White House, and his eccentric manner must have contributed to the studio’s decline. By 1962 there were only one or two people there at a time.

And yet the technique had already had a serious impact on every kind of movement training. Suki Schorer, for example, a former principal dancer at New York City Ballet and now a senior teacher at the company’s school, told me she’s still working out on her own machine:

I’ve had lots of injuries, and Pilates has always pulled me back. Dancers who wanted to get strong went to do Pilates. Mr. B [Balanchine] wanted everything bigger, faster, more powerful. I didn’t have a great extension and it got better. My jump got much better. Pilates makes you stronger, gives you more turnout, more elevation.

These days there’s even a room with Pilates equipment at the David H. Koch Theater for the company. Dancers everywhere rely on the training, and wherever I have managed to find a serious Pilates studio in the United States, some lunky athlete has eventually shown up to settle his large body obediently into the sliding carriage of the Reformer.

A handful of Joe’s devotees struggled to reproduce what they had learned in studios of their own, and it is thanks to them that Pilates technique exists today. Among them was Robert Fitzgerald, who trained grateful dancers and movie stars and worked for years with the aging Martha Graham. The first time I walked into Fitzgerald’s studio on West 56th Street, Faye Dunaway was just leaving, cheekbones clearing the way, and I wondered what I had gotten myself into.

Behind her was an assortment of metal-tube-and-leather contraptions that vaguely resembled modern furniture or instruments of torture — or, as someone said years later at another studio, wondering if he could rent it from midnight on, the setup at a highly imaginative sex club. Fitzgerald, slender, upright, and cool, was unforgettable, with a circus acrobat’s body and shoulder-length blond hair; in profile he resembled the two elegant Afghan dogs that went everywhere with him.

I was a reasonably trained aspiring young dancer making the rounds of the various dance company studios. If anyone had asked me, I would have said that in the course of all this practice every muscle in my body had been worked. Not enough, maybe, not to their full capacity, not beyond that capacity, surely, but quite a bit. I got through the catatonically boring first session of Pilates as all first-timers have done since Joe created his machines and set the initial sequence of movements: lying face up on the Reformer, learning first how to breathe while making the Mushroom (lower abdominal muscles zipped up tightly to make the stem, and the rib cage expanded sideways to form the cap), taking in as much oxygen as possible and releasing it without letting the abs relax so much as a fraction.

This maddening effort was followed by a few minutes in which Fitzgerald used his hands to make careful adjustments to my feet and knees until I was in the exact “relaxed” first-position plié, toes resting on the Reformer’s foot bar at a forty-five-degree angle, knees precisely in line with toes. Now, holding the Mushroom in place — Fitzgerald kept a stern finger on my navel — I pushed against the bar into a straight-leg first position and then flexed my knees into plié once more while inhaling and exhaling methodically and keeping my lower abdomen perfectly still.

There followed something called the Hundreds, complicated to explain but also boring, and then the leg extensions: one leg straight, foot down against the bar, the other leg straight up in the air, foot in a loop attached to a spring, now bring that leg down, slowly, against the spring’s resistance, and raise it again. Ten times each side, please. Ten or so simple exercises — not difficult at all but challenging when holding the Mushroom in place, I admitted — all coordinated with inhales and exhales, and I was done.

Two days after that first class I found myself hobbling home on a bright spring day, too sore to take steps of more than a few inches. My adductor brevis, longus and magnus muscles, and oh my god, the obturator externus, not to mention the pectineus, psoas, subscapularis, serratus anterior, transversus abdominis, and let’s not forget the gracilis, were screeching in unison at me to please stop, to not move an inch farther, because they were about to die of breathtaking pain. I shuffled on, across Washington Square and all the way home, inhaling and exhaling the Mushroom while doing grim sums in my head to see how I would ever pay for an indispensable lifetime of classes with Robert Fitzgerald.

In a matter of months at his studio all my chronic aches and pains disappeared, and I saw my body become stronger, more flexible, longer, different. I was a better dancer, more in command of my movements, able to take greater physical risks with increased self-assurance. Above all, there was the new distance between the top of my pelvic bones and the bottom of my lowermost ribs: I had acquired the characteristic Pilates body, in which the ribs appear to float weightlessly atop what is now called not the Mushroom but the “core.”

This was back in the 1970s, when the American obsession with healthy, muscled bodies was in abeyance. Pilates studios, few and far between, survived but hardly increased in number. In the 1980s came Jane Fonda, who introduced aerobics to the public at large and retained many of the exercises and principles of Pilates floorwork to strengthen the core — the abdominal muscles. There were other doyens of the VCR and television, like Richard Simmons, who wore not Joe’s embarrassing black trunks but glittery hot pants and was determined to make you Tone and Sweat — that was his mantra. What all these promoters had in common — what guaranteed their success — was that they didn’t require you to pay the slightest attention to what you were doing.

But sometime in the 1990s the significant cross-section of the US population that believes in staying fit — gym rats, runners, physicians and physiotherapists, women wanting to look good in a bathing suit, and men, too — finally got the whole Pilates thing: the silence, the concentration, the lack of competitiveness, the quasi-maniacal attention to detail, and the magical transformation of the body. Today there are Pilates studios in all fifty states and in cities around the world: Medellín and Bangkok have Pilates instructors, people who take the classes no longer need to know anything about the founder, and I am certain that the technique must have already received the ultimate enshrinement as a prestige tag in rom-coms.

Proof of the training’s continuing vitality is its ability to change. I asked Gonzalo Garcia, a former principal dancer with New York City Ballet who was recently appointed the new artistic director of Miami City Ballet, what the Pilates machines and exercises had contributed to his own impeccable technique, and he laughed. “The legs, the feet, the core. Everything, really.” Had it, then, single-handedly contributed to the great leap forward in dancers’ physical strength — the ear-high developpés, the splits à la seconde for men and the Wonder Woman arms for women that are now standard for dancers around the world? Not quite, García clarified:

There seems to be a change, an advance in the [dance] technique every ten, fifteen years or so. So now it is very athletic, gymnastic almost, and this has some good things and some things not so good at all. But then, the Pilates technique must be changing as well: many more teachers are working with Pilates, and so there is an accumulation of other knowledge about the body. There is the root and the tree, and that is very beautiful, but from that tree also come many branches.

Joe Pilates did not live to see any of this. He died a bitter and eccentric old man, raging at US society for failing to recognise the pure intuitive genius of what he had accomplished. His gigantic contribution to the strength and health of the body would be recognised only after he was dead, he announced angrily and often, and he was right. •

Caged Lion: Joseph Pilates and His Legacy

By John Howard Steel | Last Leaf | $26.99 | 195 pages

Hubertus Joseph Pilates: The Biography

By Javier Pérez Pont and Esperanza Aparicio Romero | HakaBooks | $82.60 | 518 pages

Love All Around: The Romana Kryzanowska Biography

By Cathy Strack and Carol J. Craig | C and C Projects | $35 | 289 pages