With its nuclear arsenal once again under legal challenge, Britain has withdrawn from the compulsory jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice, or ICJ, on matters relating to nuclear disarmament. The British government notified the ICJ on 22 February this year that it would no longer accept the court’s authority over “any claim or dispute that arises from or is connected with or related to nuclear disarmament and/or nuclear weapons.”

The announcement allowed one exception: cases in which all the other nuclear-weapon parties to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, or NPT, “have also consented to the jurisdiction of the Court and are party to the proceedings in question.” It came just weeks before more than 130 non-nuclear countries began meeting at the United Nations to negotiate a nuclear weapons ban treaty. Those talks resume this week.

This isn’t the first time the British government has taken such a step. Sixty years ago, facing condemnation of its proposed hydrogen bomb tests in the Pacific, it also withdrew from compulsory ICJ jurisdiction. In the Brexit era, is Britain heading back to the 1950s?

In its July 1996 advisory opinion on nuclear weapons, the ICJ determined that nuclear-weapon states are obliged by Article VI of the NPT “to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament in all its aspects under strict and effective control.” In a unanimous decision, the court has also recognised an equivalent rule under customary law, requiring each nuclear power to engage in disarmament talks.

More than twenty years later, the NPT nuclear-weapon countries are still in breach of those obligations. No multilateral disarmament talks are under way, nor even talks about talks, in UN forums such as the Committee on Disarmament. Nuclear-armed governments outside the NPT, including Israel and India, are also refusing to abide by customary law on disarmament.

Britain’s latest decision is a setback for the push for a treaty banning nuclear weapons, which is being spearheaded by non-nuclear countries. Britain isn’t alone: the other four permanent members of the UN Security Council, together with Israel and North Korea, already refuse to accept compulsory ICJ jurisdiction on disarmament. (By contrast, India and Pakistan have both accepted this jurisdiction, even though they are not NPT signatories.)

According to the non-government British American Security Information Council, or BASIC, Britain’s decision to reject compulsory ICJ jurisdiction is designed to stop “frustrated non-nuclear weapon states from bringing fresh cases against the UK for alleged failure to negotiate on the cessation of the nuclear arms race.” Britain’s declaration means that the court can only rule on nuclear disarmament disputes when the proceedings involve all five of the NPT nuclear-armed states. Announcing the move to the House of Commons, the foreign and Commonwealth affairs minister Alan Duncan said that “the government does not believe the United Kingdom’s actions in respect of such weapons and nuclear disarmament can meaningfully be judged in isolation.”

Another effect of Britain’s decision is to advance the cut-off date for historical cases to 1987. Restricting cases to the past thirty years may affect claims related to British nuclear testing in Australia (1952–57) and Kiribati (1957–58), or disputes arising from the 1985 royal commission into British nuclear testing in Australia.

The decision will also have the effect of banning governments from bringing repeat cases. In April 2014, the Republic of the Marshall Islands filed landmark lawsuits in the ICJ challenging all nine nuclear-armed nations for failing to comply with their NPT obligation to negotiate the total elimination of nuclear weapons. Because they accepted compulsory jurisdiction at the time, the cases against India, Pakistan and Britain proceeded to preliminary submissions.

By eight votes to eight (on the president’s casting vote), the ICJ dismissed the suit against Britain last October, ruling that there was insufficient evidence of a dispute between the Marshall Islands and Britain. (Is it a coincidence that six of the eight judges who found no dispute are nationals of nuclear-weapon states, while all the minority judges are from non-nuclear states?) Several judges stressed that the case was ending at a technical stage rather than after its substance had been examined.

The ICJ also ruled that the Marshall Islands has “special reasons for concern” about nuclear disarmament, because it is living with the health and environmental effects of sixty-seven nuclear tests. As BASIC notes, “The UK government’s 2017 decision would appear to cut off any possibility of the Marshall Islands bringing another case and succeeding, and likely shows that it is not confident that the court’s decision would be favourable if the substance of the case were discussed.”

Britain’s similar decision more than sixty years ago came in the face of protests across the Asia-Pacific region over its proposed nuclear-testing program at Christmas Island. The British government decided in 1956 to test thermonuclear, or hydrogen, bombs on Christmas Island and Malden Island in the British Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony – today, part of the Republic of Kiribati. Public opposition was especially intense in Japan, where popular anger over Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been strengthened by the March 1954 US hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll, codename Bravo, which irradiated the crew of the Japanese fishing boat Lucky Dragon.

A nationwide signature campaign against nuclear testing, initiated on Hiroshima Day 1954, gathered more than thirty-two million signatures. The following year, peace activists founded the national peace organisation Gensuikyo (the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs). Britain’s announcement of H-bomb tests in mid-1956 fuelled the concerns.

By early 1957, the British embassy in Tokyo was sending regular reports to London, detailing rising protests against the proposed atmospheric testing program. Fearful that Japan might take a case to the ICJ to stop the Christmas Island tests, the British government temporarily withdrew from compulsory ICJ jurisdiction.

Whenever the interests of the nuclear powers are challenged, whether it’s 1957 or 2017, a similar disdain for law becomes clear. Tony Blair went to war in Iraq in 2003 on the pretext of weapons of mass destruction, exacerbating chaos and terrorism in the Middle East. Today, London calls on states like Iran to adhere to law on nuclear weapons but refuses to act on its own NPT disarmament obligations.

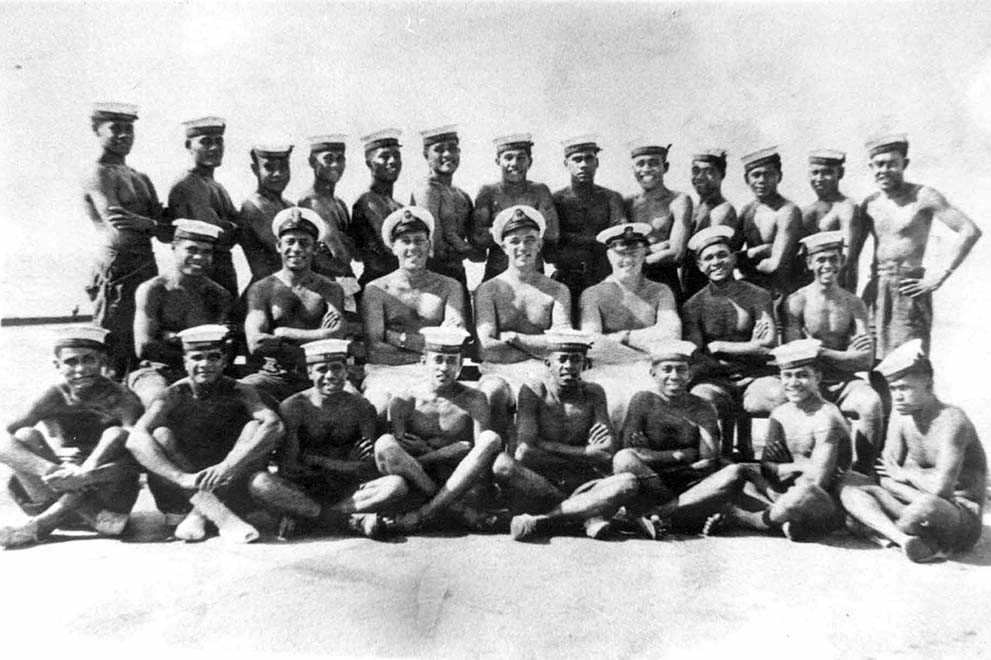

Despite its concerns over the ICJ, the UK Ministry of Defence has been prepared to defend nuclear cases in domestic courts. A 2004 case lodged by British, New Zealand and Fijian veterans of the 1950s Christmas Island tests spent ten years working its way through the British courts, with the authorities resisting every inch of the way. Defence officials appealed every temporary victory by the veterans in lower courts and refused to negotiate an out-of-court settlement. Dozens of the original litigants had died before the case was finally rejected 5–4 by the UK Supreme Court.

As talks recommence this week in New York for a nuclear weapons ban treaty, Britain’s refusal to commit to compulsory ICJ jurisdiction shows that efforts for a nuclear ban are beginning to bite. When it comes to nukes, London is running scared. •