In the early morning, there can be few more beautiful places to walk than along the tropical foreshore of Townsville in north Queensland, with palms framing views across the sparkling waters to Magnetic Island and beyond. The trail leads past cafes, swimming spots, parks and a stunning cultural display at Garabarra, also known as Kissing Point, where steel brolgas and other sculptures share some of the stories from this place and the traditional owners, the Wulgurukaba and Bindal people.

Artworks and storyboards illustrate the walk around the rocky headland, telling about Gabul the carpet python and the region’s creation story, as well as the medicinal and other uses for the soap tree and other plants that line the walk.

Embedded in the footpath are key dates in the history of colonisation, including the 1898 legislation that authorised the removal of Aboriginal people to reserves and the separation of children from families. The timeline also documents landmarks in local resistance, including when the Bwgcolman people of Palm Island called the historic 1957 strike in protest at their unjust treatment, an event whose sixtieth anniversary was recently commemorated nearby.

Lisa Paull takes this walk a few mornings each week, revelling in the views, the sense of connection to place and people, and the physical activity. Many other people are likely to be out and about, too, walking and running with prams, dogs and friends. Paull often works out on the foreshore’s public gym gear, which is where we strike up a conversation one morning in May.

Chatting with strangers is one of the pleasures of her morning ritual, in fact, along with watching the striking red-tailed black cockatoos. As the fifty-six-year-old explains, the regular workout is becoming more critical as she gets older. She needs the physical resilience to help look after her frail mother-in-law, with whom she and her husband live, and her grandchildren. “I’m not looking to do anything except keep my core strength strong, keep balance, being able to walk, keep my heart working, blood pressure down, and diabetes away.”

Body and soul: Lisa Paull exercising on Townsville’s foreshore. Melissa Sweet

A year ago, Paull was using morphine patches to help manage the pain of a degenerative spine condition. But she has been able to give them away thanks to an outdoor exercise program that has made an “enormous difference” to her life. “I’m happier than I’ve ever been,” she says. “It’s just great for your mind and your body and your soul; it’s better than sitting in a chair and letting the world pass you by.”

She goes on using the equipment while we talk. I tell her I’m heading to Ipswich, a town just southwest of Brisbane that sounds like it’s going places, to speak to the mayor, Paul Pisasale, about the work he’s done over many years to encourage the community to get active. Paull said she has heard great things about that mayor. Just weeks later, Pisasale’s term in office would end in controversy, but at this time, before the storm broke, people were singing his praises.

And so, a few days later, the setting for my morning walk is a sprawling park not far from the Ipswich CBD, where Brian Fegan, a semi-retired teacher who has lived in Ipswich for thirty-five years, has brought his ninety-one-year-old father, who is recuperating from a recent stroke. With them is Sam Tanejo, an accountant who moved from Delhi to Brisbane and then to Ipswich in search of a better life for his family.

“He heard there were two types of people,” Fegan jokes. “Those who come from Ipswich, and those who wished they had.” The men’s friendship began in the park a few years back when they met over dog walking.

When I ask them about the mayor, the two men say he is well-known for supporting community initiatives and for his unrelenting spruiking of Ipswich. Pisasale, a local councillor since 1991, was first elected as an independent mayor in 2004, and went on to win 83 per cent of the vote in last year’s mayoral election.

“I think Paul Pisasale is the most popular mayor I’ve ever seen,” says Tanejo. “When I came to Australia, Ipswich had a stigma attached to it; but once you start living here, I would say it’s one of the best places around Brisbane to raise a family. I got more active after coming to Ipswich; seeing people jogging all the time, I got more active myself.”

I leave the men enjoying their restful spot and check out some nearby public gym equipment. I’m tempted to try it out, but I’m feeling a bit sore from the previous evening’s sampling of one of the many low-cost fitness programs provided by the Ipswich Hospital Foundation. Each week, about 500 people join classes like these around Ipswich, from boxing to aquafitness and Pilates, and pay a maximum of just $5 per class.

The foundation, mainly funded with revenue raised by managing car parks at the local hospital and shopping plaza, is focused on health promotion and keeping people out of hospital — a big ask in a region with rapid population growth and a socioeconomic profile associated with poorer population health. “The scale of the challenge, it’s huge. There’s a great deal of room to improve our personal health as a region,” says the foundation’s CEO, Phillip Bell. “We are not coming from an excellent place in terms of health and wellbeing.”

Bell, who is also a farmer and president of the local chamber of commerce, was, like many, enticed to the area by affordable housing. He describes a long list of developments under way or planned in the region, including a focus on innovation and social connectivity. In 2019, the city will host an autonomous vehicle trial.

“It’s a very easy city to become passionate about,” Bell says. “A lot of it comes down to what I call the Pisasale factor. Paul is a unique leader… He is the type of mayor who gets involved when there are gaps, when people are missing out. As a consequence, we have a really strong and vibrant not-for-profit sector, and I include us in that.”

Waiting outside the mayor’s office to hear more about his role as Ipswich’s chief health promoter, I found plenty to engage the eye. Glass cabinets display hundreds of espresso cups — the Mayor’s Demitasse Collection, listed in 2008 by Guinness World Records as the largest of its kind, which Pisasale has said is valued at more than $100,000.

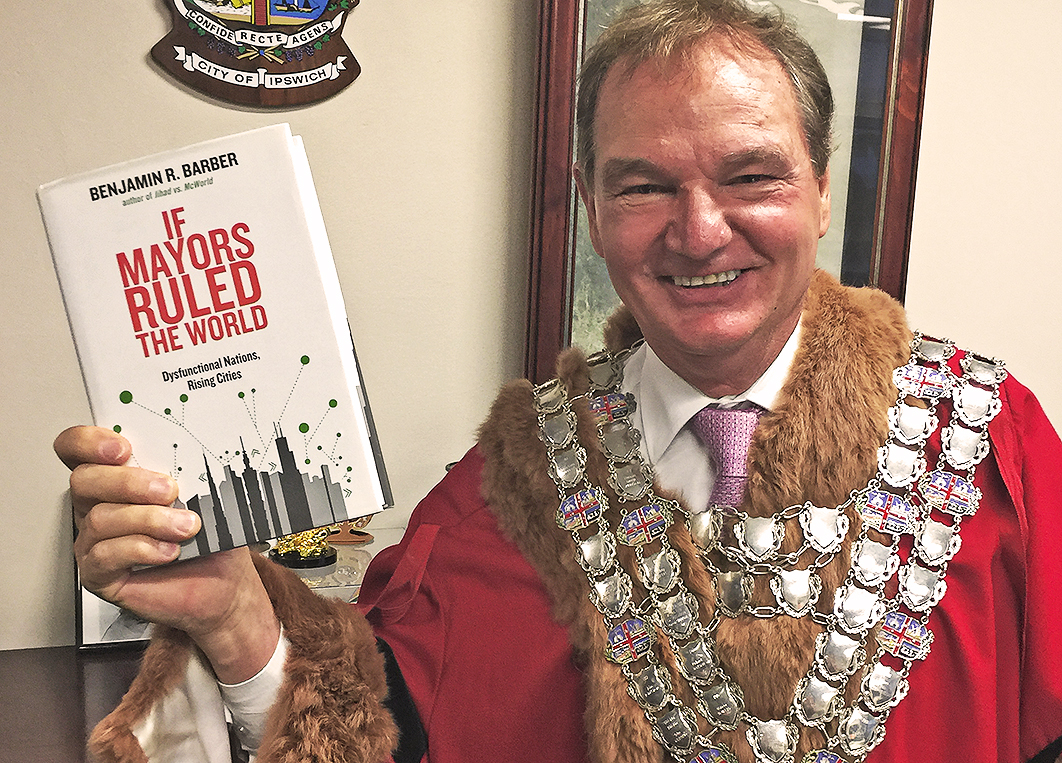

Inside the mayoral office is a life-size cardboard cut-out of the man himself, who quickly makes it clear why he is often described as a larger-than-life figure. He presents me with a gift-wrapped scarf, decorated with a City of Ipswich motif, before launching into conversation that jumps quickly from one topic to the next, linked by his obvious love for Ipswich, his drive to promote it, and his frustration with the political prioritisation of marginal seats rather than areas of need.

A better place? The then mayor of Ipswich, Paul Pisasale. Melissa Sweet

A concern for health and wellbeing also features prominently. Pisasale describes some of his own experience with multiple sclerosis, and the importance of people with chronic diseases having hope and motivation to remain active. Every time his blood pressure is checked or he takes other health measures, he posts about it on Facebook.

Pisasale also stresses the importance of community engagement and social inclusion, though these are not terms he uses, talking instead about kindness, care and compassion, and describing the city’s parties to welcome refugees. “If the [federal] government was the government when my parents came over in the big boats from Sicily, I’d be the mayor of Manus Island,” he says.

To be a great city, he says, requires taking a collective responsibility to care for all. Pisasale laughs when I produce the book I’ve been reading in preparation for the interview. I read out the title, If Mayors Ruled the World, and ask him what difference that would make. “It would be a better place,” comes his quick response.

Given the failure of nation-states to tackle pressing problems such as climate change, the book argues, it’s up to cities to save the world. There are “not many climate change deniers among mayors,” observes the author, the late Benjamin R. Barber, formerly a senior research scholar at the Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society at the City University of New York.

Barber mounts a case for a global parliament of mayors or a world assembly of cities to formalise the networks developing between cities or mayors within and across countries. “Mayors can rule the world because cities represent a level of governance sufficiently local to demand pragmatism and efficiency in problem solving but sufficiently networked to be able to fashion cooperative solutions to the interdependent challenges they face,” he writes.

Past and present mayors, from Michael Bloomberg in New York to Ayodele Adewale in Lagos and Sheila Dikshit in Delhi, figure in Barber’s account. Leaders like these, Barber argues, tend to share an all-absorbing passion for their locale, as well as focusing on fixing problems rather than on ideology or partisan politics. Pisasale isn’t mentioned in the book, but these descriptors echo much of what people say about him.

The day after our meeting, Pisasale joins local business and community members on an RAAF air-to-air refuelling mission over the Pacific Ocean. It is an opportunity to talk up his support for the local Amberley RAAF base; the stunning video clip later posted to his Facebook page attracts more than 16,000 views. “We want to make Ipswich Australia’s most prosperous and liveable Smart City,” he posts, “through a strong focus on jobs, growth and liveability.”

Later that week, Pisasale is due to fly to Melbourne to meet celebrity chef Jamie Oliver, whose first Ministry of Food program in Australia opened in the Ipswich CBD in 2011. Speaking with the staff there, it seems the mayor is one of their most enthusiastic supporters, dropping in regularly to greet those taking cooking classes, sometimes serenading them with song. “He is quite a character; it’s just amazing the support that he gives us,” says a staff member.

But there’s a surprising coda to my visit to the mayor’s office. Four weeks later, in an emotional press conference at a local hospital, Pisasale announced his resignation. A few weeks after that, he was charged with extortion and other matters, and expelled from the Queensland branch of the Labor Party.

On 17 July, Queensland’s Crime and Corruption Commission was granted an extra two months to prepare a full brief of evidence, with a further court mention scheduled for September. A mayoral by-election is due on 19 August, and some residents are campaigning for the entire council to face an election. Only the passage of time will reveal the true legacy for Ipswich of “the people’s mayor,” as he has so often been called.

Benjamin Barber published his book in 2013, and its call for more effective governance grows ever more timely in the wake of Brexit, Donald Trump’s election, and increasingly unstable geopolitics. In the United States, hardly a week goes by without media reporting on coalitions of mayors or cities for climate change action. When the Climate Council recently launched a Cities Power Partnership to support such local action in Australia, one report was headlined, “In the Absence of National Leadership, Cities Are Driving Climate Policy.”

It’s a line that raises questions for the wider public health sector. The 2014 federal budget’s cuts to public health spending left a big vacuum. For those feeling desperate — or optimistic — this opens the opportunity for other leaders to step up.

We recently saw such an example when a coalition of health groups released a framework for a national strategy on climate, health and wellbeing. Fiona Armstrong, executive director of the Climate and Health Alliance, hopes it will provide policy-makers at all levels with guidance. “When governments refuse to lead,” she says, “it is important for civil society to step in.” The coalition made detailed recommendations for health and other sectors, including calling for federal, state and territory governments to establish a ministerial health and climate change forum to oversee coordinated national action.

Once, governments might have been expected to do this work of policy development, and in other countries they have: strategies addressing climate change and health have been developed by the European Union and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States, while Britain has implemented a policy for the National Health Service that includes both mitigation and adaptation strategies.

Public health advocates could learn much from the environment movement and its long history of activism and grassroots engagement, says Michael Thorn, chief executive of the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education – not to mention, I’d add, the long history of resistance by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, as evidenced by the 1957 strikers on Palm Island and a new generation of activists, like the Seed Mob, an Indigenous youth climate network.

Thorn describes a sense of frustration and anger among public health professionals. Many are looking to develop new alliances with communities, he says, including supporting the work of local councils who are challenging alcohol retailers and pokie operators. “The paucity of national leadership has caused us all to think about what can happen at a local level… we need to try and find those leaders and encourage them and support them,” he says.

The Heart Foundation has been doing just that for some years, points out Julie Anne Mitchell, director of cardiovascular programs for the foundation’s NSW Division. “Our first experience of really working well with local councils was back in 2007 when the state government had just banned smoking in pubs and clubs.” Since then, she says, the government has resisted taking action on smoking in outdoor public places.

The NSW Division began working with a few local councils that supported the measure, and over the next five years ninety-eight of the state’s 152 councils adopted some form of smoke-free outdoor areas policy. Most were in Sydney, but the move created a groundswell of support for statewide action, says Mitchell, and the NSW government was brought to the legislative table in 2012.

Testing public policy: the National Heart Foundation’s Julie Anne Mitchell.

Working with local councils also involves engaging environmental health officers to encourage food outlets to switch from saturated and trans-fat oils to healthier oils. Cessnock Council has been “the standout example of this strategy,” says Mitchell, reflecting local concern about the area’s high rates of heart disease. In 2012, 12 per cent of small food outlets in Cessnock were using healthier oils; after three years of the Healthier Oils Program, two-thirds were. Buoyed by that success, the foundation is widening the campaign; the huge Penrith Panthers Leagues Club in western Sydney is estimated to have removed a tonne of saturated fat from its menu each year as a result.

The goal, says Mitchell, is to persuade the state government to put its might behind the program, making it part of the job description for environmental health officers. “It is often the role of NGOs to test public policy because we run ahead of where the government’s appetite is set,” she says. “It’s only through testing these cases that we get enough of a groundswell that convinces politicians in a way that a report or a commissioned piece of research never will.”

The Heart Foundation is a member of the CycleSafe Network, a coalition that has worked with the Newcastle City Council, doing the hard slog in developing a plan for a 140 kilometre active transport network across the Newcastle and Lake Macquarie local government areas. A CycleSafe report says 63 per cent of people in the area are overweight or obese, 1 per cent currently cycle to work, and air pollution is often above recommended levels.

The aim is to make walking and cycling for short trips — less than two kilometres for walking and less than ten kilometres for cycling — a viable alternative to car travel, and accessible for children, the aged and people with reduced mobility. The network would not only boost health and the environment, but would also be a great opportunity for tourism and regional development, Mitchell says, pointing to the experience of Portland in Oregon. It would also provide a blueprint for other regional communities, she adds.

Despite strong local support, Mitchell says the state’s Coalition government looks unlikely to back the CycleSafe plan, despite the $1.75 billion sale of the Port of Newcastle. This is not a marginal seat; the local Labor MPs have solid margins.

Meanwhile, Mitchell and colleagues are advocating for forthcoming amendments to the NSW Planning Bill to incorporate a focus on health. Such a change would be a huge enabler for local councils, providing much-needed support in the practical ways they could embed physical activity and food policies locally. “If we could get health into planning, we should also have it in transport. It is a way of getting health across government.”

The push to implement health in all policies, known as HiAP, is gaining increasing traction, according to a manual for local government in Britain: “HiAP is based on the recognition that our greatest health challenges — for example, non-communicable diseases, health inequities and inequalities, climate change and spiralling health care costs — are highly complex and often linked through the social determinants of health. Just one government sector will not have all the tools, knowledge, capacity, let alone the budget to address this complexity.”

This isn’t rocket science. To flourish, we need healthy, sustainable environments; decent living conditions; inclusive and culturally safe societies that tackle poverty, racism, discrimination and trauma; and access to the basics — affordable housing, quality education, active transport, quality healthcare, healthy and affordable food, safe drinking water and high-quality internet.

Yet there are so many roadblocks, as the National Rural Health Conference in Cairns heard earlier this year. The chair of the Northern Queensland Primary Health Network, adjunct associate professor Trent Twomey, described the importance of dealing with the social and economic factors that determine health and ill-health. Using a series of maps, he showed the lack of alignment between the boundaries governing education and training, police, local government and health services in his own network’s region, including thirty-one local government areas with thirty-one mayors.

“It is extremely difficult for regional Queenslanders to have control over their destiny if the boundaries of all the different state and federal agencies don’t line up… The system of government, whether state or federal, is basically designed against us,” Twomey said. “Communities of interest” would be a much better way of determining the boundaries of governments and service providers, he argued. Only in that way would local communities be empowered “to take control of our destinies in a planning process.”

Given the obstacles to such massive institutional reform, though, might there be other ways to act local, and to subvert all the jurisdictional, sectoral and organisational silos and roadblocks?

One approach has been building steam in southwestern Victoria, where a community-based health movement is being forged in public meetings that bring together representatives from all walks, including local organisations and government. Participants are given tools, developed and continually updated by Deakin University researchers and community leaders working together, to map the complex factors contributing to weight gain in local children and to identify where change is possible. The process helps shift focus from individual behaviours towards topics such as urban planning.

These collaborative modelling processes have made a powerful contribution to new networks for action, says Janette Lowe, one of the leaders of the collaborative GenR8 Change movement, and director of the Southern Grampians Glenelg Primary Care Partnership, based in Hamilton.

Primary Care Partnerships are funded by the Victorian government to develop and support local cooperation between local governments, health services and community services organisations. They provide a platform for local innovation, says Lowe, and that’s important for driving wider policy. “Government is not in the innovation and early adoption space,” she says. “They’re in the space of when things become mainstream.”

Lowe recalls a meeting of about sixty people in Portland, a coastal industrial town, in 2014. The group modelled and mapped obesity prevention, producing many “aha moments” as people began to appreciate that “this is a whole of community problem and this is where I can influence it.” It was a very empowering process, she says. “It isn’t about someone coming to fix your problem, or coming to a workshop to get information about you. People go away very motivated and there is a real buzz.”

As well as the usual concerns — like junk food marketing and the costs of children’s sport — community members said the taste of drinking water in Portland was contributing to demand for sugary drinks. Wannon Water is working to address these concerns, and is also installing public drinking fountains across the region. Acting managing director Ian Bail and his colleagues are also investigating what more the organisation can do for public health, as well as how to apply the whole-system thinking from public health to their business.

“We would love to see our region flourish,” Bail says. “It is about that local connection. That encourages us to work with a range of other agencies, to say, how can we improve liveability of our towns in a collaborative way?

When similar group modelling workshops were held in Hamilton, to the north of Portland, community members subsequently reported that more than 180 different actions had resulted. Lowe says these included changes in the food provided in school canteens and day-care facilities, and one woman initiating a “ride to school bus” that collected local children to cycle to school each morning. “Some of the biggest change-makers are your passionate mums or people from the community who aren’t necessarily in an organisation,” says Lowe.

Along the way, Rohan Fitzgerald, CEO of Western District Health Service and formerly a local councillor, has emerged as a powerful voice for public health in a way rarely seen among health service executives. Meeting Deakin’s Steven Allender has, he says, “hooked” him on the need for a paradigm shift at his organisation. Sugary drinks haven’t been sold on its premises since 2015, a move that has been followed by some other public health services in Victoria and, more recently, New South Wales.

Fitzgerald is also behind a petition to federal parliament calling for a sugar tax on sugary drinks. “I don’t know of any other public health services that have petitioned the federal government to introduce a sugar tax,” he says.

The research team has deliberately maintained a low profile to ensure communities devise their own tools for change and take responsibility for the outcomes. Community volunteers were trained to collect data on the height, weight and behaviour of children, creating a level of engagement that meant far greater participation rates than usual. The received wisdom from national data is that 25 to 30 per cent of children are overweight or obese, but prevalence rates of 27 to 52 per cent were found among primary school students in the Southern Grampians in 2015 (varying according to age and gender), according to a GenR8 Change report back to community via YouTube. “So it’s way more of a problem than we thought,” says Allender.

Timely access to this local data has been important for engaging the local communities in devising solutions, says Janette Lowe, including working closely with the local newspaper, which, she says, has been “one of the great leaders in our community.” Great care is taken to ensure the data is not used in a way that causes stigma. The 2017 survey results are due soon, and Lowe is hopeful they will see improvements in health-related behaviours, such as children being more active, as a result of all the community’s work.

Meanwhile, the pair are turning their sights to the national stage. Allender is seeking philanthropic funding so the model used in southwestern Victoria can be shared more widely. “We have a waiting list of about one hundred communities around the country who want to get involved,” he says. Lowe is hoping to run a series of national workshops to mobilise communities more widely. “My big mantra at the moment is, I’m not going to wait for government,” she says. “It’s about passionate people coming together to make change.”

The distribution of health in any society is essentially a reflection of who holds power and how it is wielded. Can local mobilisation help to counter the powerful interests that undermine our health in a time of political and policy capture and inertia? Perhaps this is not an entirely new question, but it is being asked with a new urgency. •

The assistance of the Copyright Agency Limited’s Cultural Fund in providing funding for this article is gratefully acknowledged.