Do biographies of living politicians affect their careers? Sometimes, as with campaign biographies, that’s what they’re intended to do; at other times, the impact might be unintentional.

When Julia Gillard was deputy prime minister, Chris Wallace began work on an unauthorised biography. Kevin Rudd’s government had yet to flounder on the shoals of his inability to manage the business of government and deal with factional ambitions. Gillard was in line to be Australia’s first female prime minister, but not yet, and not in circumstances where she could forever be blamed for stabbing Rudd in the back.

By the time the biography was finished and about to be published by Allen & Unwin, Gillard was prime minister and leading a minority government. Her ascension to power, both the fact and the manner of it, had unleashed an appalling campaign of misogyny, sanctioned if not overtly led by opposition leader Tony Abbott, supported by right-wing journalists and carried in a stream of filth on social media. She was also being undermined from within, by Rudd and his supporters.

As publication date approached, the publisher’s publicist told Wallace to expect a media frenzy. Gillard’s enemies were waiting to pounce, to comb the book for dirt.

Wallace already knew how a biography can be used against its subject. In 1993 she had published a biography of then opposition leader John Hewson, who looked likely to defeat Paul Keating at the forthcoming election. Her motivation was public interest — Hewson was relatively unknown — but the Keating camp scoured the book for scandals and insights into Hewson’s vulnerabilities.

This could happen again, she realised. Gillard is a human being and had her flaws, but Wallace didn’t want to contribute to the destabilisation of her government and the election of the Abbott-led alternative. So she pulled the book and paid back the advance. She felt, she told her disappointed publisher, that she had “no other moral choice.”

“I did not intend the Gillard biography to help or hurt Gillard’s political fortunes,” she writes in her new book, Political Lives: Australian Prime Ministers and Their Biographers. “When I conceived it, I did not foresee its potential exploitation by ‘bad actors’ in the supercharged political climate which developed.”

The experience got her thinking about other political biographers who had written about living subjects. Did any of their books influence their subjects’ career, for good or ill? So she embarked on a PhD, researching every biography written during the active career of every twentieth-century Australian prime minister and interviewing every living Australian PM and every living biographer of a contemporary PM.

What becomes clear as the book proceeds is that her question really only applies to the period since Whitlam became leader of the Labor Party in 1967. For the first half of the twentieth century her research question barely applies. Before John Gorton, only two contemporary biographies of prime ministers — of Billy Hughes and John Curtin — were published.

But Wallace did discover some unpublished gems in the archives: Herbert Campbell-Jones’s “The Cabinet of Captains,” which covers the first six prime ministers, and Alfred Buchanan’s “The Prime Ministers of Australia.” Both men were journalists, as have been most of the writers of contemporary biographies.

Also in the archives was a manuscript biography of Robert Menzies by Allan Dawes, based on interviews with Menzies undertaken in the early 1950s, before his electoral dominance was established. Wallace speculates that as Menzies’s popularity rose he saw less need for a humanising biography.

In the first half of Political Lives, rich in detail, Wallace proves herself to be a consummate archival detective. One example touches on my own work. Part of the Dawes manuscript is in Menzies’s papers at the National Library, and I drew on it for my book, Robert Menzies’ Forgotten People. But Wallace found more in Dawes’s papers, where I hadn’t thought to look. What she found has much historical interest, though the men and the times are now a long way from popular memory.

The second, livelier half of Political Lives begins with Alan Trengove’s book John Grey Gorton: An Informed Biography, which revealed the potentially controversial fact that John Gorton’s mother was unmarried. Published after Gorton succeeded Harold Holt as prime minister in early 1968, and cleared by Gorton himself, the revelation had little impact on his reputation. But it marked a turning point in Australian contemporary political biography. Revealing rather than concealing personal information now became an option, and politicians could consider managing the release of awkward facts.

But the genre really takes off with Gough Whitlam. When he became Labor leader in 1967 he was little known outside political circles, and many of those who did know of him were puzzled as to what this supremely confident, urbane, middle-class man with a penchant for quoting the classics was doing in the Labor Party. In 1970 the young Laurie Oakes began researching a biography, though Whitlam PM didn’t appear until late 1973, a year after Labor won office.

Oakes’s book was a revelation to many, especially in its account of his subject’s childhood and parents. Growing up in Canberra as the son of the Crown solicitor made Whitlam a social democrat with a belief in the capacities of government to improve people’s lives.

Oakes wrote a quartet of books about Whitlam (two of them with David Solomon), but Whitlam’s great biographer was his legendary speechwriter, Graham Freudenberg, who was so close to Whitlam that he could speak on his behalf. Freudenberg’s A Certain Grandeur was published in October 1977, after Whitlam’s government was dismissed and just before the election that would be his last. The book didn’t have enough time to influence the outcome of the election, after which Whitlam retired from active politics, but it did put the travails of his government into the broader context of the economic and political forces that battered it.

The book that most fits Wallace’s question is Blanche d’Alpuget’s biography of Bob Hawke, published in 1982 when he was positioning himself to wrest the leadership of the Labor Party from Bill Hayden and become prime minister. D’Alpuget, a successful novelist, had just completed a well-regarded biography of Sir Richard Kirby, former president of the Conciliation and Arbitration Commission. She knew Hawke well — they were lovers — and he trusted her to write a “warts and all” biography, with his womanising and drinking included alongside his political achievements and talents.

Through Angus McIntyre, whom she had known when she was living in Indonesia with her diplomat husband, d’Alpuget had got to know Melbourne University’s Graham Little and others in the Melbourne Psycho-Social Group, a loose association of academics, psychoanalysts and therapists interested in the application of psychoanalytic ideas outside clinical settings. D’Alpuget’s biography is far more psychologically acute than the usual political biography, with a rich account of Hawke’s childhood and family relationships, especially with his difficult and demanding mother.

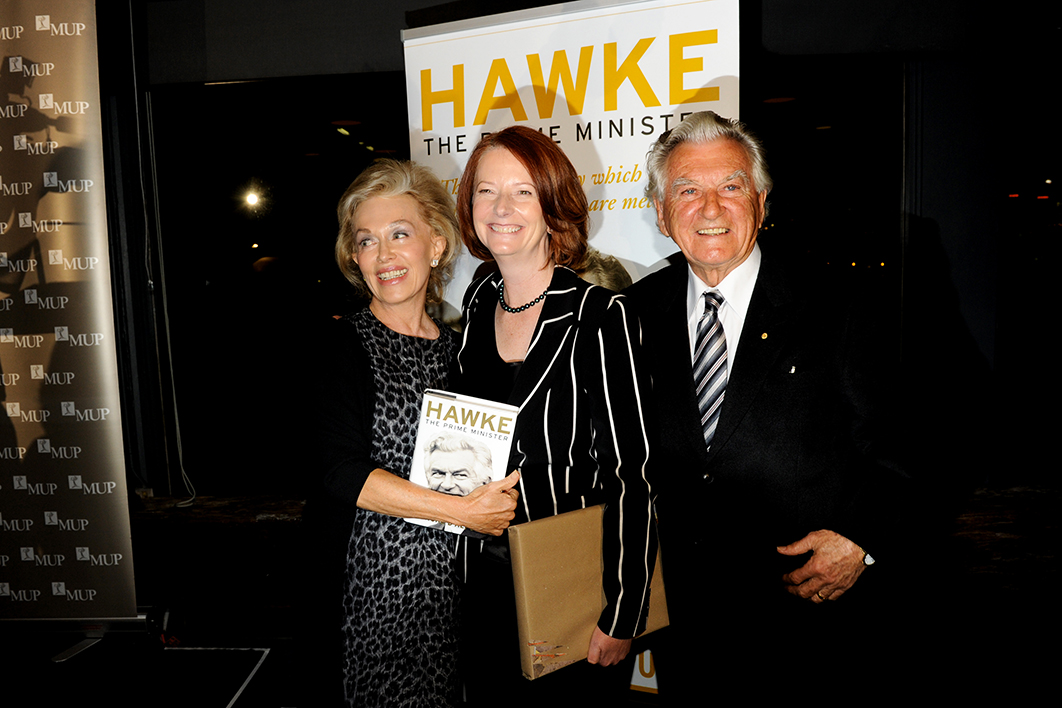

The book gave the Labor caucus a more nuanced understanding of the man, winning him votes in the leadership contest with Hayden. More interestingly, it gave Hawke greater insight into himself. D’Alpuget conducted long interviews with him, stirring up memories of his childhood which, she believed, helped him conquer his compulsive drinking. Wallace’s chapter on Hawke, with its intriguing insights from d’Alpuget about how she wrote the book, and its effects, is the highlight of Political Lives, and d’Alpuget and Hawke appear on the cover.

Wallace also discusses Stan Anson’s Hawke: An Emotional Life, published just after Hawke had survived a leadership challenge from Paul Keating. Anson made overt use of psychoanalysis and ideas of narcissism to understand Hawke, and drew heavily on d’Alpuget’s account of Hawke’s childhood. She was furious and threatened legal action under the Trade Practices Act, accusing Anson of passing off her work as his own.

Wallace concludes that the fuss stopped psychoanalytically informed biography dead in its tracks in Australia, at least when it came to contemporary politicians. This is probably true, but it doesn’t mean that psychoanalytic ideas disappeared from writing about Australian politics. Psychoanalysis was one of the intellectual traditions shaping my Robert Menzies’ Forgotten People (1992) and Graham Little drew on psychoanalytic ideas in the profiles of leading politicians he published in the press and in his last book, The Public Emotions (1999).

Wallace ends her book with a plea for more psychologically sophisticated biography writing. Most contemporary biographies of politicians are written by journalists, who often uncover hitherto unknown facts but are generally short on ideas and thin on interpretation. That’s why d’Alpuget’s biography of Hawke stands out, as does, more recently, Sean Kelly’s The Game, a devastating dismantling of Scott Morrison’s smoke and mirrors.

Kelly may not have drawn explicitly on psychoanalytic theories, but by paying close attention to his subject’s language and characteristic rhetorical strategies he showed what can be done within the bounds of the genre. His book probably didn’t damage Morrison’s political fortunes, however. That was something Morrison was already doing for himself. •

Political Lives: Australian Prime Ministers and Their Biographers

By Chris Wallace | UNSW Press | $39.99 | 336 pages