Apart from their similar-sounding names, Australia and Austria have at least one thing in common. Both countries have long skiing traditions, and for historical reasons they have features in common. From as early as the 1930s, Austrian ski teachers taught their skills to generations of Australian skiers, transmitting knowledge across the world from St Anton, Zürs and other skiers’ meccas to the Australian Alps. Migrants from Central Europe, many of them from Austria, served as informal cultural brokers and helped develop a multibillion-dollar industry during the postwar boom years.

One of them was Charles William Anton, who was born almost exactly a century ago and died fifty years ago. Having escaped from Nazi persecution in occupied Austria, Anton built up Australia’s largest ski club with enthusiasm and commitment, drawing on ideas he had acquired in Austria’s Alpenverein, or Alpine Club, in the interwar years. Although he set out with the simple aim of establishing an organisation for mountaineers and alpinists in Australia, he soon became one of the driving forces in the promotion of the winter-sport industry and mass winter tourism in general.

The centenary of Anton’s birthday is a chance to show how he took an imported concept and created a successful organisation that differed greatly not only from contemporary Australian ski clubs but also from its Austrian model. And it is also a reminder of the many roles migrants have had in the development of Australia.

Charles William Anton was born Karl Anton Schwarz in Vienna in 1916. The son of Jewish migrants from Poland and Slovakia, he grew up in a liberal, middle-class environment. Like many young Viennese, he discovered the alpine regions around Vienna and developed a passion for ski touring.

Of the several organisations that had already built up skiing and mountaineering infrastructure in the Alps, the largest was the Alpenverein, which operated a dense network of shelter huts. Young Karl made intensive use of that infrastructure. As a friend of his later said, “Charles and his friends, with a pack on their backs, would finish up almost every night in a different alpine Hütte [shelter hut].” This gave him broad insight into the value of offering security and shelter for skiers on extended tours of alpine terrain, and a detailed knowledge of the club’s operations.

He attended the Technologisches Gewerbemuseum in Vienna, an elite technical secondary school known for its high educational standards. After obtaining his leaving certificate in 1935, he worked for a British insurance company, making him one of the very few people in interwar Austria who had the experience of working for a major international company. After the German occupation in 1938, his compulsory military service was cancelled and he was dismissed from the Austrian army. Although he had been baptised a Catholic, he and his family were classified as Jewish by the Nazis and, like about 200,000 other Austrians, subject to a series of discriminatory and later deadly measures defined in the Nuremberg Laws.

Karl Anton, as a friend of his later put it, “saw the writing on the wall” and prepared for his family’s escape to safety. After a short, intensive search, he found himself a job at a Jewish-owned insurance broker in Sydney, thereby managing not only his own but also his parents’ escape from persecution. Despite rigorous restrictions, he managed to bring some of his family’s financial assets to Australia, and he was later able to buy an investment property in Sydney.

Charles Anton and Tony Sponar, another migrant from Central Europe, were the major figures behind the development of the ski resort at Thredbo. They are shown here at the site in summer 1956. Geoffrey Hughes

Soon after his arrival in wartime Australia, he changed his name by deed poll, and he subsequently tried to join the Australian armed forces. “I sincerely hope that you will give me the chance to do my bit in this war which after all is as much our war as it is yours,” he wrote to a recruiting officer in 1940. In March 1942, he was drafted to the 3rd Employment Company in New South Wales, a new, unarmed military body that refugees were eligible to join. In July 1945, a few months after he obtained citizenship, Private Anton was transferred to the Australian Imperial Forces.

In September 1945, as a participant in inter-allied ski races at Charlotte’s Pass in New South Wales, he experienced what he called his first “taste of Australian skiing.” The races reawakened his passion for ski touring. In the following years, he explored the NSW Alps, describing them as “miles upon miles of glorious ski country comparable to the European Alps.”

Skiing in Australia, and especially in New South Wales, was very underdeveloped. There were no more than a couple of hundred skiers in New South Wales and only a handful of state-owned lodges. With accommodation scarce, each of the few existing exclusive ski clubs concentrated on building up a lodge for their members, most of whom were wealthy and well-connected. Membership was expensive and not easy to gain.

Charles Anton sniffed his chance. In Austria, he had learned about a club that was open to everyone interested in mountaineering and able, he said, to “handle the dangers of the mountains.” He had been an active member of an alpine club that developed infrastructure across alpine territory to allow its members to tour through a wider terrain. Australia didn’t have that kind infrastructure, and Anton was going to change that.

In 1950, he convinced “the major figures of New South Wales’s skiing community, as well as high-ranking representatives of the State Park Trust, the Government Tourist Bureau, and the Ski Council of New South Wales,” to support the founding of the Ski Tourers’ Association, STA, with the aim of “establishing a chain of ski lodges across the alps.” His organisation followed the cooperative “concept of the Alpenverein,” as he later described it, whereby autonomous clubhouse projects affiliated to form an association with a common institution. Starting with the first, a Hütte at Lake Albina, STA built up a network of four huts, together with Australia’s highest ski tow, at Mt Northcote, within the first six years of its existence.

With its open-access policy and comparatively low membership fees, STA grew rapidly. By 1956 it was Australia’s largest ski club, with a membership of more than 500 skiers from New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania. Anton turned out to be an advertising expert. “No one could match Charlie in these things,” Leon Smith, his successor as president of the Australian Alpine Club, told me earlier this year. His qualities as an insurance broker, a profession he maintained until his death, proved to be essential for his undertakings in the snow business. From gluhwein parties and lederhosen fashion shows to the construction of entire huts as copies of Tyrolean chalets, he did much to promote the opening of new ski lodges. His events became legendary.

In many ways, 1956 was a turning point for Anton and the STA. In that year, his beloved Kunama Hütte, named after an Aboriginal word for snow, was destroyed by an avalanche and the engine hut of the ski tow at Mt Northcote by fire. At the same time, new environmental and safety policies were making the erection of new huts on exposed mountainous terrain more difficult. Skiing in general had also changed dramatically, turning from a leisure activity for a handful of affluent people into a mass industry. Ski tows, hotels and private lodges had mushroomed in the original ski resorts and Australian skiers had higher expectations of ski accommodation. The Australian Alps were no longer underdeveloped terrain, and Anton’s initial idea needed to adapt to the new conditions.

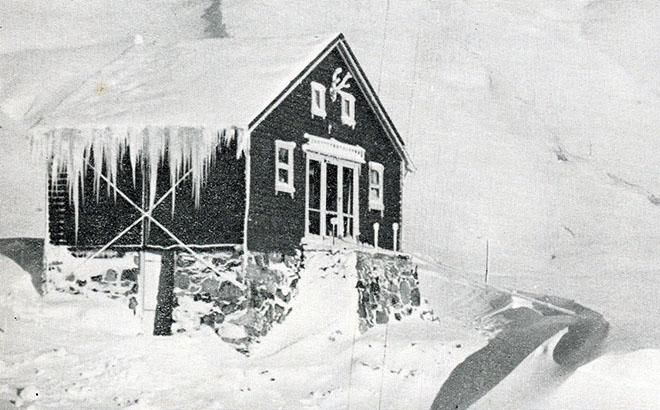

Kunama Hut, under Mt Northcote and Mt Lee, destroyed by an avalanche in 1956. AAC

He had observed international trends and was in close contact with experts in Austria, where skiing had turned into a major branch of the economy and an engine of economic growth. He had learned about the importance of mass winter tourism and become increasingly aware of demand among the emerging middle class for readily accessible ski accommodation. Very soon, he decided to change the direction of his club, adapting the plan to keep opening up the Alps to mountaineers through a network of shelter huts. Instead, he focused, in his own words, on luxurious “accommodation lodges in promising ski resorts,” which he strove to keep open to a broad cross-section of postwar skiers. Inevitably, though, the nature of the STA changed.

Anton dreamed of opening “a ski carousel á la Kitzbühel [a famous ski town in Austria]” and from the late 1950s until his death he immersed himself in the foundation of new ski resorts. He was one of the founders of Thredbo, Australia’s “most international ski resort,” according to the ski historian Peter Southwell-Keely, and developed plans to open up a second ski resort in Victoria. At a tourism conference in Hobart in 1961, he suggested Australia should focus on the estimated ten million American skiers and should “cash in on that trade by providing first-class facilities.”

During his later years, he was intensely focused on the expansion of Australia’s winter sports industry. He unilaterally renamed STA the Australian Club to emphasis its national significance. Along with the new name came an expansion into other states: by the time of his unexpected death in 1966, he had built up two club lodges in Victoria and had developed plans for a second ski resort comparable to Thredbo.

During the entire period, Anton managed to maintain a successful insurance business in Sydney. He married three times and raised three children. Despite his determination to become a “true” Australian, he maintained a fondness for his old home’s cultural paraphernalia. Austrian culture was visible in many areas of his life. He even furnished one of his flats in Sydney as a copy of a Tyrolean peasant’s home.

Patscherkofel Lodge, named after the famous Innsbruck 1964 Winter Olympic ski run, was Anton’s last project. He died of a rare form of meningitis on a ski trip to his very first ski lodge, Lake Albina Hut, on 17 September 1966. “Some of the colour has gone from the Australian snow scene,” reported the Canberra Times. A year after his death, the NSW lands minister, Tom Lewis, announced that an unnamed peak near Mount Kosciuszko would be named Mount Anton “because of the substantial contribution of Mr Anton to advancing Australian skiing.”

Charles William Anton was an example of a successful “cultural agent” who brought ideas into his new homeland and adapted them successfully to meet the new demands. Thanks to his commitment, effort and knowledge, he was able to build up the largest ski club in Australia, and the country’s “most international skiresort”. His successful efforts to publicise skiing secured him a central place among the founders of postwar skiing in Australia. •