The election campaign battle over Medicare should come as no surprise. It echoes disputes during previous campaigns that have their origins in ideological divides dating back to well before Medicare was founded. Labor sees the health of Australians as a matter of sufficient national importance that it requires government intervention; the Coalition sees it more as a matter of personal responsibility and individual choice.

The compromises struck in order to enact Medicare have meant that Australia’s healthcare has been a blend of public and private systems, with precise relationships, both competitive and cooperative, never fully delineated. The pendulum has swung in favour of one or the other aspect – public or private – depending on who is in government and the financial pressures of the times.

Political and voter reactions to these swings are compounded by the efforts of key stakeholders to protect their own interests. Organised medicine, most obviously the Australian Medical Association, has been a powerful and disruptive player in healthcare politics, driven primarily by the fear that governments of both political persuasions will interfere in their conditions of work and pricing power.

The AMA has a love–hate relationship with Medicare and a tradition of opposing key health reforms, good and bad, from both political parties. Their price for agreeing to the introduction of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme in the 1940s, extracted from then opposition leader Robert Menzies, was a referendum to change the constitution to prohibit any form of “civil conscription,” thus effectively making a socialised system like Britain’s National Health Service impossible and shaping the role of private providers in the delivery of Medicare services.

Together these issues highlight why Medicare is so vulnerable to claims of privatisation and why these claims have validity. It is disingenuous of the Coalition to claim it has no intention of privatising Medicare when this option has clearly been considered; and it’s important to remember that the Coalition has said nothing that would preclude private initiatives from competing alongside Medicare. History shows that while ideologies may be temporarily cast aside for political gain, they are never abandoned.

The fight to introduce Medicare was bitter and protracted. During 1973 the Coalition twice blocked the enabling legislation for Labor’s first version, Medibank, in the Senate, and it did so again after the election in 1974. This forced a joint sitting of the parliament in August 1974, which finally passed the bill by ninety-five to ninety-two votes. Notwithstanding its election commitment to keep Medibank, Malcolm Fraser’s Coalition government, which came to power in November 1975, dismantled the program in all but name.

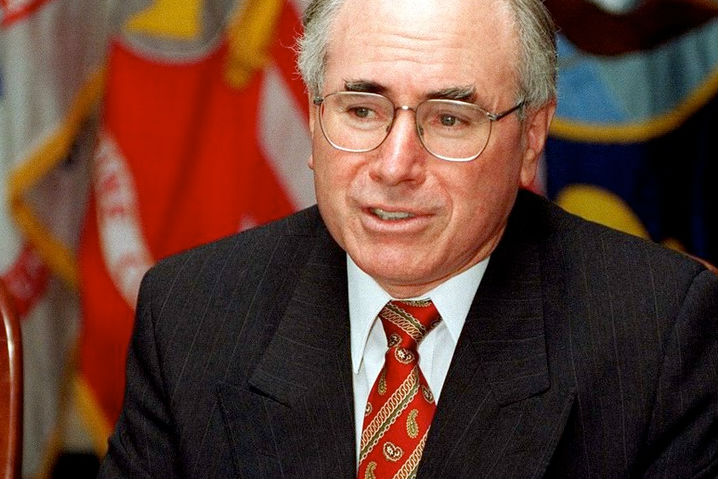

Labor returned to office in 1983, having pledged to reinstate “the basic principle of the right of all Australians to health services according to their needs.” The following year, under prime minister Bob Hawke, the government reintroduced the original model, now called Medicare. For all of the following twelve years in opposition, the Coalition remained strongly opposed to Medicare. As opposition leader, John Howard spoke out often and vehemently. He declared Medicare a “disaster” and a “nightmare” and promised that under his government “bulk-billing under Medicare would go, except for those classified as disadvantaged and there would be the option of belonging either to Medicare or to a private health fund.”

It was only in his push to win the 1996 election that Howard realised he needed to reassure the electorate about the future of Medicare and bulk-billing. He conceded that his commitment to retain Medicare was based on a pragmatic view of voters’ priorities rather than on his party’s political convictions or a change in the system itself: “It’s not a question of whether it’s become better. It is a question of us believing that Medicare is seen by the overwhelming majority of the Australian community as an important part of the social security infrastructure.”

This commitment was undermined by his government’s push, using a series of financial carrots and sticks, to bolster the uptake of private health insurance, and by its erosion of bulk-billing rates. An effective Labor campaign around bulk-billing and rising out-of-pocket costs saw an interesting set of responses from the Howard government. In 2003, it introduced a $900 million policy package, A Fairer Medicare, which was highly criticised by all stakeholders. A parliamentary inquiry report described the package as “a decisive step away from the principle of universality that has underpinned Medicare since its inception.” Its enabling legislation was blocked in the Senate.

With the 2004 election looming, the government, with Tony Abbott as health minister, announced a compromise policy package called Medicare Plus (soon to become Medicare Plus Plus, after Abbott negotiated a deal with Senate independents to ensure its passage). The new arrangements included higher reimbursements for doctors who bulk-billed and an Extended Medicare Safety Net aimed at addressing out-of-pocket costs. As bulk-billing rates climbed and safety net payments burgeoned, Abbott declared the government “Medicare’s greatest friend.”

These Howard–Abbott policies were enacted in support of political ideology (in the case of the private health insurance rebate) and out of a pragmatic need to address voters’ demands (in the case of Medicare changes). There was little evidence to support the changes, and their financial imposts and impact on equity remain as serious problems for the healthcare system.

The Extended Medicare Safety Net tied the amount of Medicare benefit to the doctor’s fee rather than the Medicare reimbursement; with no government control over specialists’ fees, the safety net was predictably a recipe for fee inflation. Not surprisingly, that means the vast bulk of the benefits find their way to high-income electorates. Costs have grown rapidly despite parameter adjustments by both Coalition and Labor governments.

In the 2014–15 budget, the Abbott government revealed plans to “simplify” Medicare safety net arrangements. The enacting legislation was rejected by the Senate in 2015, though, over concerns about the impact on chronically ill Australians and the reductions in outlays ($267 million over the forward estimates). Health minister Sussan Ley promised further consultations but there is no evidence these have occurred.

The private health insurance rebate is one of the most contentious issues in health policy. The 2016–17 budget papers show that it currently costs $6.5 billion annually, and both the rebate and the cost of health insurance premiums are allowed to grow at rates well beyond those deemed acceptable for Medicare and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

It’s an anomaly – some would say an outrageous one – that “private” health cover is so heavily subsidised by the public purse. Despite this, less than half (47 per cent) of Australians have private hospital cover. There is no evidence that the private health insurance rebate is achieving its policy intent, and it has been a significant factor in driving up costs.

Economist Saul Eslake says the rebate should be scrapped. “Subsidising people to do something they would do anyway is a waste of taxpayers’ money,” he wrote earlier this year. “The rebate reduces the discipline on health insurance funds to keep their premiums under control. And it’s a form of middle-class welfare that the country can no longer afford.” Figures from the Parliamentary Budget Office show that ditching the rebate could save the federal government as much as $10 billion over the next four years.

Yet, despite all the evidence and the criticisms from a wide range of health experts, Tony Abbott was right when he said that “private health insurance is in our DNA.” This is certainly true for the Coalition, but successive governments of both persuasions have failed to convincingly articulate why Australians need what is increasingly a duplicate healthcare system – with duplicate costs for many – and why the federal financial contribution to private health insurance should be so substantial.

Since coming to office in 2013, the Coalition has undermined public confidence in a public, universal healthcare system with talk about budget unsustainability and the overuse of Medicare services. A surreptitious shift from public to private is occurring via increased co-payments, the abolition of bulk-billing incentives, the freezing of Medicare fees to doctors, and other measures. Out-of-pocket costs are the fastest-rising part of the healthcare budget.

Expert advice requested by the government has more overtly supported privatising Medicare. The 2014 National Commission of Audit raised the possibility of requiring higher-income earners to take out private health insurance for basic health services in place of Medicare. Like the Harper Competition Policy Review, it also advocated an expanded role and less regulation for the private health insurance sector. Responding to the Harper review in November 2015, the government committed to commissioning a Productivity Commission review of how competition principles can be applied to the human services sector.

The government has also signalled its agenda to allow private health insurance to play an expanded role in primary care. Some of the larger funds are already expanding their activities in this sector, but with little regulatory oversight.

Despite the prime minister’s protestations that moves to outsource the payment systems for Medicare and the PBS do not constitute the privatisation of Medicare, the public is rightly sceptical. It’s surprising that the AMA is not similarly concerned. Semantic games have gone on about what constitutes privatisation and about the differences between Medicare payment systems and Medicare services, as have disputes about whether the findings of advisory groups and calls for expressions of interest can be said to indicate certain actions, and what the new buzz words of “competition” and “contestability” really mean for healthcare. More forthright statements from the prime minister might actually help his case here.

The risk is that Australia is headed stealthily but inexorably towards a two-tiered healthcare system in which those with resources and access can purchase the services they want, regardless of need, and Medicare becomes a ragged safety net for the less well-off. Labor’s scare campaign is biting because enough voters remember where we have been with Medicare policies and can see where we are headed. The Coalition would do well to read the results of a 2008 poll that showed a striking preference for public over private healthcare, with those surveyed clearly favouring an improved public healthcare system supported by the public purse. •