At the launch of a report on China and cybersecurity in London earlier this year I asked one of the authors which was the greatest threat to American democracy — Facebook or the Communist Party of China. With disarming speed, she replied the latter. It was clear she thought I’d asked a very dumb question.

I’m not so sure, given recurring anger at Facebook’s promotion or suppression of information, evident recently in the toxic row over whether it withheld news of the activities of Joe Biden’s son Hunter in the days before the 2020 election. Facebook may not pose the same kind of challenge as China does, but it seems wrong to assume so blithely that its behaviour doesn’t raise very serious questions.

Fears about China, on the other hand, are far from new. In 1955, having spent almost a decade in the People’s Republic before moving to Canberra, the political scientist Michael Lindsay berated the government in Beijing for what he regarded as its harsh and unfair response to Britain’s attempts to create some sort of pragmatic relationship. Hardly an apologist for the capitalist world, the left-leaning Lindsay argued that Britain had taken a big risk in January 1950 when it recognised the new regime despite American opposition. And yet, “again and again,” he wrote, “Chinese policy and Chinese publicity has done exactly what was required to strengthen the influence of the anti-Communist extremists [and] discredit the influence in British countries or America working for better relations.”

Almost seven decades later, it would be hard to express the current mess more succinctly. China’s worst diplomatic enemy, more often than not, is the Chinese government itself.

So it seems strange that Alex Joske — whose work has “shaped the thinking of governments and policymakers globally,” according to the publisher of his new book, Spies and Lies: How China’s Greatest Covert Operations Fooled the World — seems to believe China is blazingly successful in dealing with the outside world. The greatest achievement of China’s spies, he writes, has been “to convince influential foreigners that China would rise peacefully and gradually liberalise.”

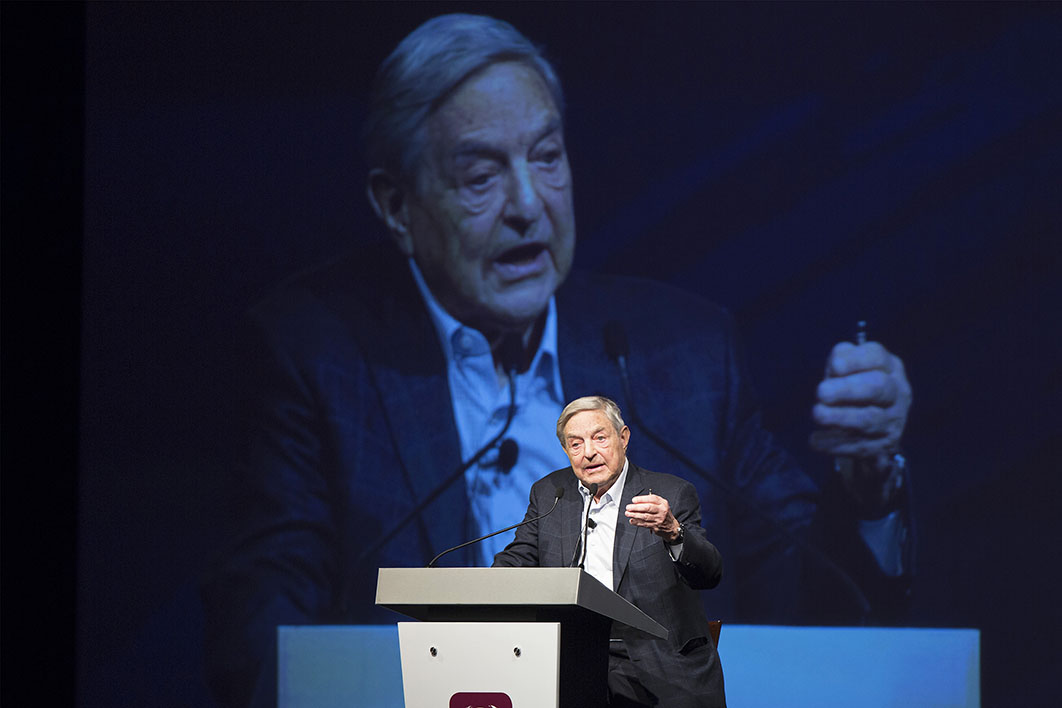

Joske’s claim implies that suddenly, sometime in the 1980s, the United States, Europe, Australia and their political allies became docile parties onto which the cunning Chinese foisted the great fib of Chinese liberalisation. Among the people who fell under the spell of the Chinese propaganists, he argues, was billionaire George Soros, who worked with reformist author Liang Heng and others. During this period Soros’s Open Society Foundations made grants and offered technical support in an attempt to create civil society groups in China.

Joske doesn’t engage with the more complex possibility that, regardless of what the Chinese government was saying at the time, there were entirely logical reasons to think China might liberalise politically, along with evidence that significant interest in this different path existed deep within the government and across Chinese society.

Many factors helped block the hoped-for liberalism. But I would submit that clever pre-emptive scheming by the “hardliners” in the party elite, and their servants in China’s intelligence network, was not prime among them. Indeed, what is striking in the period up to 1989, when the dream of Chinese liberalism was perhaps at its strongest, is how open-ended and unpredictable the situation was, and how often the party elite seemed to have no clear idea of what it was aiming for.

Everyone agreed that political reform was necessary. But no clear consensus emerged, on either the destination or the best route to reach it. That confusion gave the most conservative wing of the leadership a strong advantage when the Tiananmen Square protests erupted in mid 1989. The dominant response within the party was simple: better the devil you know than the one you don’t, as long as it delivered order and stability.

Geopolitical trends reinforced this onset of cautiousness, the most important being the huge missteps by Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, which created the worst sort of precedent for countries like China as they looked to liberalise their governance. China’s Ministry of State Security, Joske’s bastion of hardliners (though that too may be disputable), certainly took advantage of these crises, but the idea that it, and its allies in the hardline wing of the Communist Party, controlled an epic and successful misinformation strategy reads to me like history being bent to theory.

Joske does make the important point that we need to better understand what the Chinese party state, and some of its chief agents, are up to. His chapters on the strange case of Katrina Leung, who for many years was a Chinese agent within the FBI, provide useful insights. What is more fascinating, though, is the fact that she ended up marrying her handler on the American side, James J. Smith, years after conducting an affair with him and long after being exposed as an agent for China.

Whether this book, with its very clear and up-front convictions, will help much in conceptualising and handling Chinese covert influence campaigns is another matter. In his description of the latter career of soft-power proponent Zheng Bijian, and the China Reform Forum Zheng chaired in the years of Hu Jintao’s presidency, it’s clear Joske has a dim view of the gullibility, pliability and general cluelessness of many of those exposed to the language of “China’s peaceful rise.”

In his view, people like John Thornton, director of the Global Leadership Program at Tsinghua University in Beijing, and former Australian prime minister Bob Hawke were purposely recruited to push out misleading statements about China’s intentions. Presumably Joske has met some of the figures he is so critical of and put his claims to them: that would have been fair and transparent. His point may have some merit: Hawke was a perennial attendee at the increasingly awful annual exercise in groupthink with Chinese characteristics, the Boao Forum for Asia, in the years before his death. But just how much help he and his ilk gave to China’s cause is a moot point.

Effectiveness, after all, is the one issue Joske seems unwilling to tackle. Can we truly say that Chinese efforts to hoodwink the West, even if they were as streamlined and strategic as he claims, have produced the intended outcome?

I can only speak from my own experience working on, and in, China over the past quarter of a century. I remember the chaotic influence campaigns in the first decade of the 2000s, and how clunky their messaging was. In my personal encounters during those years of economic plenty, Chinese figures looking to influence the outside world generally seemed unwilling to say much at all.

Joske doesn’t provide this context, but it is important: the “peaceful rise” endorsed by Zheng and his ilk received significant pushback from diplomats in the United States and elsewhere, and had to be changed to “peaceful development.” And it was the United States, through figures like Robert Zoellick, that was asking China to say more about what its intentions were. This left the Chinese in a quandary — maintain silence and be judged untrustworthy, or speak and attract claims that everything coming out of your mouth was insincere and misleading.

Under Xi Jinping, China’s general diplomatic and security work became more disciplined and streamlined. The Ministry of State Security was hit with the same “anti-corruption” cleansing as everyone else, losing a vice-minister and many lower operatives. How effective it is these days is hard to say, but it’s worth remembering that this mighty, well-resourced entity seems to have had no real clue about Vladimir Putin’s plans for Ukraine.

Joske would no doubt appreciate that one can be a good spy but a poor analyst. Had China really mounted an effective, well-run campaign along the lines he describes in this book, I’d argue that it would not be in its current position. Relations with the West are almost universally bad and — to give one small but telling example — a plenipotentiary in Britain is currently banned from visiting parliament.

That counter-evidence won’t stop this book gaining a decent audience. The ultimately comforting story it tells — of a world in which the good West faces the bad China — is well entrenched and recently re-energised. A significant piece of research has yet to be done on just how many financial and intellectual resources have been put into this narrative by think tanks, media and others. Joske himself works (or has worked — it is unclear if he still has an affiliation) for the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, which has been accused of sometimes producing analysis that fulfils the hawkish requirements of its Canberra governmental funders.

Let’s be pragmatic: if most people accept this book’s somewhat terrifying account of Chinese government influence, there will be healthy commissions and streams of work for years to come for those who want to pursue the same line of thinking. I don’t for one minute deny the sincerity and conviction of Joske’s argument, or the quality of his data gathering and research, but I do wonder about his conceptualisation and interpretation. He describes a world my own observations don’t validate, and one I find hard to believe actually exists. •

Spies and Lies: How China’s Greatest Covert Operations Fooled the World

By Alex Joske | Hardie Grant | $32.99 | 272 pages