The main purpose of government is to promote the welfare of its people. Other things matter, too, but without this core value government moves from being the solution to becoming the problem. That is exactly what has happened in many of Australia’s social services.

In key fields — childcare, aged care, employment services and the NDIS — what we have is not a quality system of care but a disordered ecology of self-directed providers and distant regulators. Governments write complex contracts and rain down new rules when things go wrong, but they haven’t improved the systems themselves. We pay a high price for poor quality and often fraud-ridden services.

Royal commissions, parliamentary reviews, Productivity Commission reports and dozens of independent studies show the same pattern. Successive federal governments have dealt with rising demand for social services by encouraging private companies to form a quasi-market and then encouraging citizens to search for services that suit them.

The new vocabulary of social service reform became the offer of greater choice, with the power that might create for each individual to get what they want and for services to thus become highly responsive. The engine driving this imagined process was the failed idea that unhappy customers will simply exit a bad service and thus “signal” to producers that they must lift their game.

The problem with this “choice” model is twofold.

First, new service markets don’t suddenly spring into life across the social spectrum, waiting for customers to stroll in and make their selections. They are completely different from products: they can’t be produced in advance or shipped in the post or compared on a supermarket shelf. They are created at the same moment they are consumed. They require personal delivery and careful connection to the communities they seek to serve.

Second, these services are extremely difficult to regulate from a distance. We only know how good a service is when we experience it or when we observe, up close, someone else experiencing it.

What current services offer is a “buyer beware” warning and a distant form of regulation that catches the occasional rogue but misses the day-to-day defects across the system. That’s the reason the aged care royal commission found that the majority of people in our old folks’ homes were malnourished. That’s the reason thousands of people were duped by vocational education providers signing them up to ghost courses.

The “choice” idea turns out to be a stalking horse for something else altogether. It enables governments to withdraw from social services. Top public servants now like to say they are “steering, not rowing,” which has come to mean that they lack knowledge of how services are actually produced and experienced. The choice revolution has become a means of risk shifting.

Of course, choice itself is no bad thing. Everyone likes to have a choice when it comes to the important things they have to do. But that raises critical questions. What kinds of options can clients choose? And do they want to be left to figure all that out themselves? When US researchers asked a sample of the general American population if they want to choose their own cancer treatments, a strong majority answered yes. But when they asked people who actually had cancer, only a small number said yes. What they wanted was access to quality medical advice and a chance to be fully involved in decisions. That’s not choice, that’s voice.

The services in Australia’s service “markets” are a wide mix of the great and the ghastly — which is exactly what we would predict. Not all private providers are rogues, but it is also true that they all put shareholder value first; that’s the whole point of the market model. And once fraud becomes a regular event, heavier regulation and reputational damage become common.

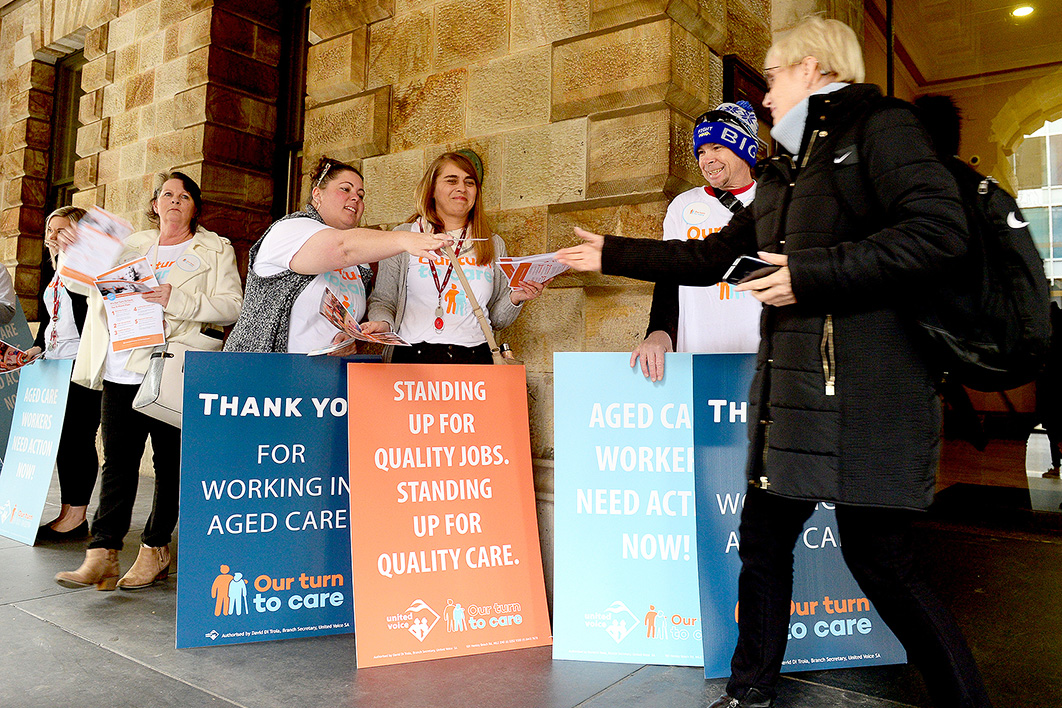

This system produces a low-average model with some core characteristics. The owners of the services seek to increase their margins by de-professionalising the service and stocking it instead with poorly paid and untrained staff. Because they all do it and because they are all paid the same rate by the government, they face no market risk if they run a service that conforms to a poor minimum standard. Only the truly dreadful get noticed by the regulators.

Where a star-rating system is used to show consumers how the different providers are doing, the low-average system means that the best service only has to be slightly better than its terrible comparators in order to score points.

With weak oversight of the service itself, providers are tempted to put their best effort into marketing their service to would-be clients. If you browse the websites of aged care homes you will see that most offer “home-cooked meals” and a “place like home.” But no one knows exactly what that means until they move into a centre, which may be too late. Childcare centres promise educational activity, but there is no way to know if that ever happens or for how long in the average day.

Service providers also work very hard to get the maximum subsidy they can from the government. Many seek to reclassify their clients as more needy than they really are, or delay helping them solve smaller problems so the bigger issues will generate greater subsidies. Charges meanwhile rise faster than the average in the broader community because users receive government money to cushion the blow. These dynamics help explain one of the great paradoxes of these service markets: they can become more expensive at the same time as they deliver worse services.

These tragic conditions are well known inside each of the sectors. Sadly, the better operators get tarred with the same brush as the worst. “It is a matter of luck whether our most vulnerable and forgotten citizens end up in one of these shitholes or living a good life” is how one market player described rogue operators in the disability sector.

In that contrast is the clue to the way out of this terrible mess. Instead of a chaotic world of high-risk choices, we need to redesign these services with high, transparent standards of care built in. And we need those receiving the services and those supporting them to have a strong voice in their development and delivery. Throwing more money at the problem won’t make a jot of difference until a more systemic approach kicks in.

The good news is that many of the changes needed aren’t expensive, and some will actually save money. Services need to be better grounded in communities, which will require a more imaginative social investment strategy than has been evident to date. And shared expertise will need to play a bigger role within these services so we can promote the best solutions and share the best methods.

Each of these services has its own dynamics and will require specific reform. But common problems also need to be tackled. The first and most dramatic challenge is to make services more transparent by defining the core activities and standards of all service providers and building in the peer reviewing and evidence sharing that make real-time improvements possible. An agreed model of delivery must combine the best interests of clients with an efficient and responsive approach to current users and future demand.

With transparent models of service will come a greater capacity to share useful adaptations and innovations and use resources creatively. Regulation will also be cheaper and less time-wasting. A common service model would also give employees access to training to increase their skills and to participate in sector-wide benchmarking and self-improvement.

A second area for structural change involves the necessary shift from choice to voice. By all means, let’s keep systems that involve multiple agencies. Nothing is improved by going back to a single bureaucratic supply model — if ever such a thing existed. But let’s move past the myth that these systems will improve because consumers can simply move to the better option and thus drive out poor performers. Multiple suppliers are useful when they offer specialisation and community-specific capability, not when they seek to out-compete some carbon-copy agency down the street.

What really drives improvement is a stronger voice for clients and their families. More mechanisms are needed to help these “experts of experience” make a positive contribution to agencies’ performances. For example, public funds should come with the requirement that the agency has a client board that is consulted about all the key issues.

The third area where change would generate significant benefit is in infrastructure. By over-relying on private markets for core social services we have drifted away from public assets and weakened our planning capacity. Public payments for individual users include contributions to service infrastructure, but these assets reside in private hands and can’t therefore be used for maximum benefit. New models for private–public partnership are needed to build services for the future.

Local governments often provide the planning approval for such facilities but cannot manage them over their lifespan. As a result, aged care, childcare and training facilities are often built to optimise real estate value rather than to develop joined-up services such as joint childcare and aged care facilities.

Finally, we need to re-establish the role of public service providers within the broader mix of agencies. The public service can’t improve a service it doesn’t understand using staff who have no frontline capability. Public service delivery should always drive for high standards, test new methods and activate the “flanking services” — including counselling, rehabilitation and housing assistance — needed to make complex services work. And a “provider of last resort” should always be ready to move to places where market players won’t accept risks associated with long-term investments in clients.

There’s an alternative, of course: we can keep doing what we have been doing for twenty years and watch the most vulnerable in our community get ripped off and done down. It’s not a great choice. •