An optimist, someone once said, is a pessimist not in full possession of the facts. The estimated 25,000 people attending COP26 in Glasgow could be forgiven for wondering if it might not be the other way round.

The case for pessimism was made eloquently — if perhaps unintentionally — by Sir David Attenborough in a powerful address to the Leaders’ Summit that opened the conference on Monday. Tracing the precipitous rise in the concentration of carbon in the atmosphere over the past hundred years, the ninety-five-year-old naturalist reached a simple conclusion: “We are already in trouble.”

The prime minister of Barbados, Mia Mottley, was even more brutal in her speech in response. The developed world had failed to meet its promises to cut emissions and provide financial assistance to the poorest countries. The cost, she said, would be measured in lives, and in livelihoods. “It is immoral, and it is unjust.”

Both Attenborough and Mottley insisted humanity can still turn things around. But listening to the rhetoric of the 119 leaders whose speeches filled the next two days — all of them stressing how much their countries were doing, despite most of the facts showing otherwise — it was hard for the rational brain not to feel overwhelmed by pessimism.

The facts are pretty simple. To have a reasonable chance of limiting global heating to the UN goal of 1.5°C above pre-industrial times, global emissions need to be cut by 45 per cent by 2030. On current trends they will rise by 16 per cent.

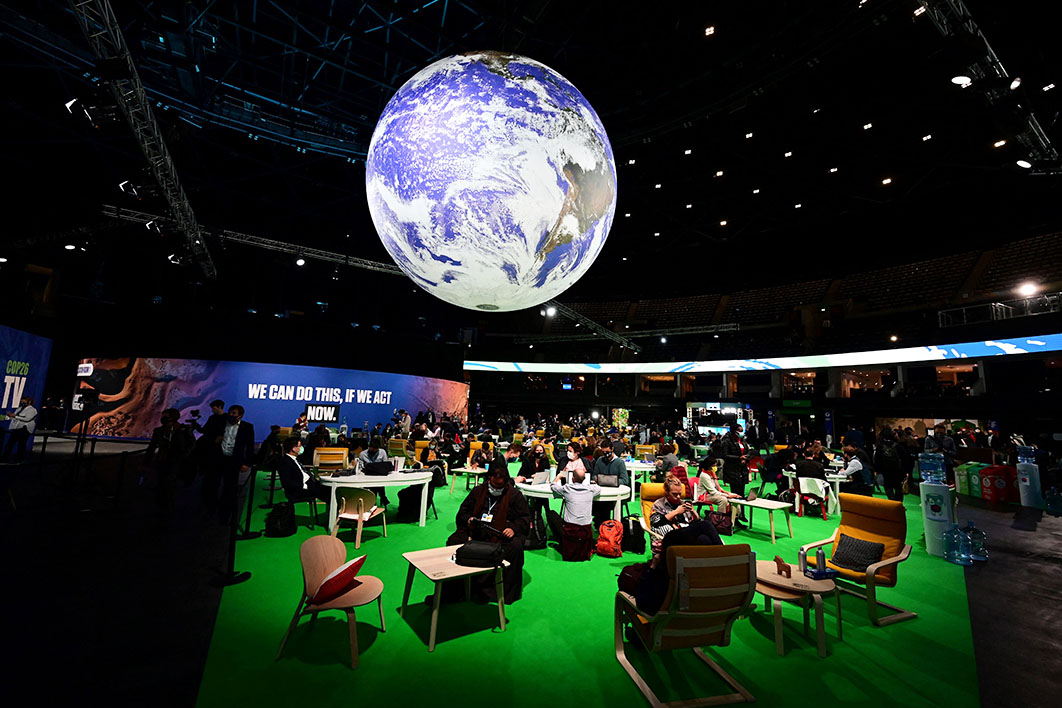

And yet COP26 is strangely a place of extraordinary optimism. This is mainly a function of its structure. Most of the 25,000 attendees aren’t country negotiators here for the UN climate talks, who probably number around 2500. The rest are people who work professionally on climate change, for businesses, charities and activist groups, universities, city and regional governments, and myriad others. They are here not to negotiate but to sell their wares, meet their international colleagues and network tirelessly.

For a COP is never just — or even mainly — a UN negotiating meeting. It is the world’s annual global climate expo and conference. And almost everyone who comes has a positive story to tell about how they are tackling climate change in some way. For some reason the climate sceptics and the opponents of climate action don’t seem to regard themselves as welcome, and they don’t show up.

So walk among the country and business “pavilions” in the middle of the conference centre — a slightly grandiose name for a series of pop-up stalls and exhibits — and the good news is relentless. Every country is doing so much to tackle the problem, from renewable energy to flood defences, sustainable transport to overseas aid. Every business is committed to “net zero,” engaging its eager workforce in meeting the goal. Every technology company has a world-leading solution, from green hydrogen to drought-resistant crops.

And every hour of the day all the side rooms are full, hosting hundreds of fringe meetings on every possible aspect of climate change. And here too the mood is powerfully feel-good. Of course most of them start with speakers recounting how dire the climate situation is. But they quickly move on to what can be done to tackle it; indeed what their organisation is already doing, in partnership with local communities and local businesses, supported by benevolent financiers and researched by concerned academics. The poorest people in the world may be suffering from severe climate impacts, but a lot of people claim to be helping them.

Observing all this it is easy to be cynical. But it’s also hard not to be affected. It can only be a good thing that a global climate industry of this scale and variety exists. There will surely be no solutions without it. And it has contributed to the remarkably upbeat mood of the official COP proceedings in the first few days.

The negotiations themselves have barely started. An agenda was agreed on the first day — you might think that this would be routine, but plenty of seasoned negotiators saw it as something of a triumph — and the committees and working groups on key issues have held their opening sessions. But most of the attention has been taken up by a series of side agreements carefully choreographed by the British hosts. And the extent and ambition of these have taken many by surprise.

The first was on deforestation. A new pact was announced between more than a hundred governments, representing over 85 per cent of the world’s forests and including Brazil, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo, pledging to halt and then reverse deforestation and land degradation by 2030. Donor countries would give US$12 billion for forest protection and restoration; many of the countries, companies and financial institutions most involved in trading forest products, including timber, pulp and palm oil, would eliminate deforested areas from their supply chains.

After forests, methane. US president Joe Biden announced that ninety countries had agreed together to cut methane emissions by 30 per cent by the end of the decade. Methane, produced from agriculture, oil and gas, and landfill sites, is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide: if fully implemented, the pledge could limit global heating by about 0.2°C by 2050.

Green technologies were next in the spotlight. Forty countries, including the United States, China, India, the European Union, Britain and Australia, signed up to a “Breakthrough Agenda” to coordinate the global introduction of clean technologies, starting with zero-carbon electricity, electric vehicles, green steel, hydrogen and sustainable farming. The governments said they would align standards and coordinate investments to scale and speed up production. The aim is to bring forward the tipping point at which green technologies are more affordable and available than fossil-fuelled alternatives.

Then it was the turn of finance. Mark Carney, former governor of the Bank of England and Britain’s climate finance envoy, announced that financial institutions holding US$130 trillion of assets under management had committed to hitting net zero emissions targets by 2050. Including more than 450 banks, insurers and asset managers across forty-five countries, the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero said it could deliver as much as US$100 trillion of financing to help economies decarbonise over the next three decades.

Not everyone applauded all this. Observers noted that a very similar agreement on forests had been announced at the UN Climate Summit in 2014. Nothing much had happened since then; would this time really be any different? It was pointed out that China, one of the world’s largest sources of methane, had not joined the new agreement. Several other green technology initiatives over the last ten years, including a “Mission 2020” platform announced with great fanfare in Paris six years ago, had proved disappointing.

The finance announcements attracted the most criticism. Non-government organisations quickly pointed out that the financial institutions were not promising that all the financing would be focused on environmentally friendly companies. Many of the banks and pension funds would only be greening a small proportion of their portfolios while happily continuing to invest in fossil fuels. The “net zero” commitments of the firms whose shares they owned were in many cases pretty dubious, resting on “offsetting” mechanisms (such as buying trees in developing countries) that can’t be guaranteed to have any effect.

And yet these agreements can’t be wholly dismissed. Many involved a large number of countries that had not previously signed up to such pledges; and most came with a lot more money — both public and private — than previous attempts. A specific agreement between South Africa, the United States and several European countries to help South Africa move away from coal particularly impressed observers: it included both significant policy reform and serious financial support.

These side agreements have a slightly strange relationship to the main negotiations. Formally, they have nothing to do with them: they do not involve the universal participation of the 197 parties to the UNFCCC (the Framework Convention that governs the talks) but rather are “coalitions of the willing.” Most of them involve private sector partners that have no formal place in the UNFCCC.

Yet in another sense they are clearly part of the process of cutting global emissions and increasing climate-related finance, which are the two main goals of COP26. Indeed, they are rather more concrete manifestations of this than anything negotiated in the conference hall. So the British government is trying to find a way of bringing them into the final COP agreement. In particular it wants to show how these agreements will help close the emissions gap between the 1.5°C trajectory demanded by the science and the current total of country pledges. Initial analysis has been uncertain: it’s possible that these sector-specific emissions reductions will be the means by which the “nationally determined contributions” of the participating countries will be achieved. Or it could be that they will enable those contributions to be exceeded.

And the nationally determined contributions themselves have also received a welcome boost in the first few days. China and India were the only two major countries who came to the COP without having announced new commitments for 2030. When it did come, China’s statement added nothing to what it had already pledged. Coupled with president Xi Jinping’s non-appearance at the Leaders’ Summit, it has made many observers question China’s current stance: a country that once prided itself on being the champion of the developing world is appearing to absent itself from this crucial moment.

India, by contrast, announced a much more ambitious contribution than anticipated. Speaking in his leader’s slot, prime minister Narendra Modi declared that India would commit to net zero emissions by 2070, and half of its electricity production from renewables by 2030. The former — a later date than China (which has committed to net zero by 2060) and apparently too late to be compatible with the 1.5°C goal — seemed disappointing to some. But scientific observers noted that this was not necessarily the case: it was indeed too late if Modi meant net zero carbon dioxide, but not if he meant net zero from all greenhouse gases. And the renewables pledge was truly ambitious: with India’s proportion of renewable electricity currently under 20 per cent, a more than doubling in less than ten years is a startlingly radical goal.

And so the early feeling in Glasgow is considerably happier than many had feared. More side agreements are still to be announced, including on phasing out coal and electrifying cars. No one will admit to expecting that COP26 will be a raging success. But some are allowing themselves a small boost of optimism. •