Australian Bush to Tiananmen Square

Ross Terrill | Hamilton Books | $37.99 | 287 pages

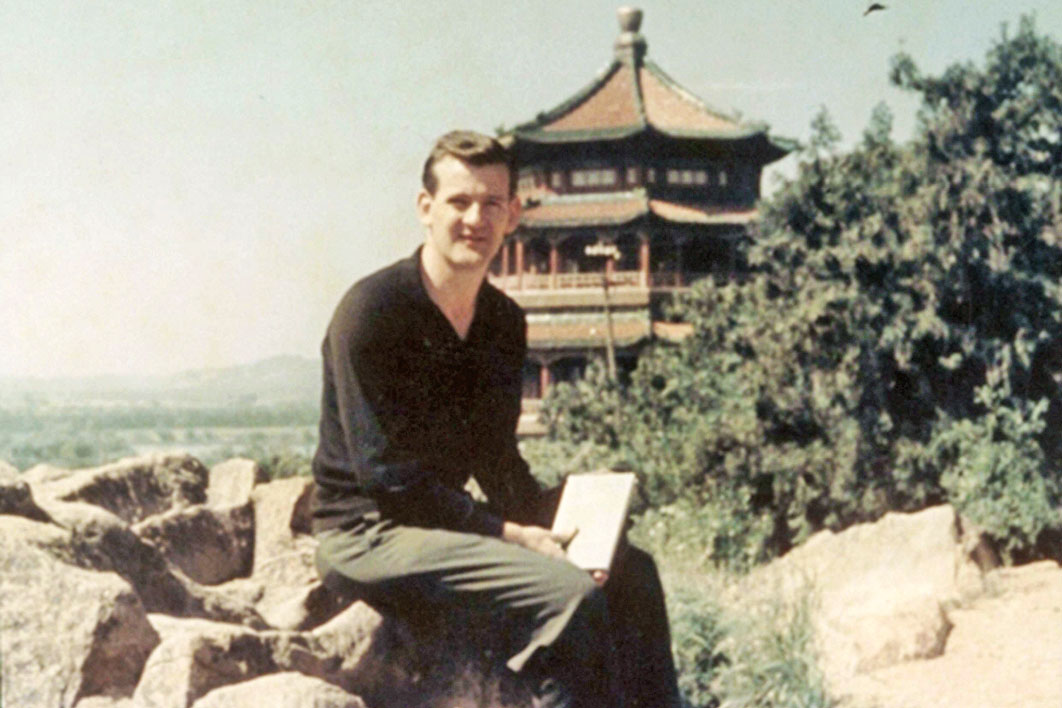

Accompanying Gough Whitlam on his history-making visit to China in 1971, Ross Terrill met Zhou Enlai for an evening session in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People:

“Premier Zhou Enlai asked me with a smile, ‘Where did you study Chinese?’

“‘In America,’ I replied, a little surprised the world-famous premier had even understood my poor Chinese, with its Australian accent, let alone showed an interest in my studies.

“Zhou Enlai said with spirit: ‘That is a fine thing, for you, an Australian, to learn Chinese in America!’”

So begins Australian Bush to Tiananmen Square, the story of a boy from country Victoria who falls in love with Asia’s giant and becomes a Harvard professor. This Australian, who “grew up in a society fearful of China, because of the Korean War,” found his “inspiration to be a writer in interaction with China.” Australia, China and the United States “were to be the three countries shaping my life.”

The bush for Terrill is Bruthen, in a valley 300 kilometres east of “far distant” Melbourne. “The sounds of a Bruthen night return as if I had just woken there,” Terrill says. “The mellow chime of bellbirds. A sighing wind in the eucalyptus trees.”

As a country child of the 1940s, shoes were for church on Sunday and everyone went barefoot to school. “This was not because of poverty, but closeness to nature,” Terrill writes. “Climate was benign. Paths of soft earth and green grass were gentle on our sunburnt toes. We learned to look out for the occasional snake.”

From studies at Melbourne University, he wangles his way into the People’s Republic of China. “Few Westerners set foot in the PRC then. Australians needed permission from their own government to go there. Some got a green light, but Beijing guarded visas for people from non-Communist countries like precious jewels. Australia, in step with the US, still had not recognised Mao’s government, which made getting a Beijing visa tougher.”

Hitchhiking Eastern Europe in the summer of 1964, Terrill knocks on the doors of China’s embassies in Prague, Budapest and Belgrade, feeling like he was “in a revolving door, with a Chinese visa always just out of my grasp.” At his last stop in Warsaw, almost out of money, the boy from the bush boldly asks to see the Chinese ambassador. “Two cups of tea appeared before us; I made my case, offering the dubious opinion that the youth of Australia’s opinion of New China hinged upon my visit.”

Next day he got that rare visa, and the adventure began. Flying via the Soviet Union, he begins exploring the “shimmering abstraction” of Mao’s revolution. “I was too young to buy an abstraction, and energetic enough to hunt down a few realities.”

Beijing offers him the curved tiles of the Forbidden City’s palaces, the nasal cries of hawkers and stone grinders, the smell of Chinese noodles and sauces, and the open-air, leisurely sightseeing of a pedicab (although it might be “unsocialist” to be pedalled around by a Chinese worker).

In Canton, the clip-clop of wooden sandals on the pavements had almost given way to the rustle of plastic shoes. “It makes Canton quieter than before Liberation,” a shopkeeper tells him. The Pearl River is alive with boats, “some were sampans, with boxes of chickens affixed to the back, home for families who refused to live ashore, despite government efforts to remove them as a pre-Liberation relic. The only (live) cat I saw in China was on the deck of one of those sampans.”

He writes a six-part series on the 1964 China trip for Rupert Murdoch’s newly created newspaper, the Australian. Murdoch himself edits Terrill’s pieces: “He pruned my articles with a blue pencil and wrote out the payment cheque with a fountain pen.”

Wanting to learn Chinese and study modern China, Terrill applies to universities in Europe and the United States. Harvard and the London School of Economics both offer a PhD fellowship. Harvard wins because of his “hunch that life in the US would suit me better than life in ‘Mother England,’ as my grandmother called Britain.”

Initially, the US consul in Melbourne denies a visa because Terrill favours diplomatic recognition of China and opposes the Vietnam war, making his “views are incompatible with American national purpose.” To reverse the verdict, the Labor leader, Arthur Calwell, writes to the American ambassador, arguing that Terrill “is a social democrat with no communist connections.” Terrill heads off in 1965, “one of the very few people at Harvard who had been in Mao’s China.”

A decade later, Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew, visiting Harvard, remarks how hard it is for Americans “peering through a peephole” to get a clear view of China. “We Westerners don’t really understand China,” Terrill replies. “We invent Chinese Communist society according to our wish.”

Terrill’s “inventing” of China is more subtle than most. After a dinner in Hong Kong, he reflects in his diary on the contrast between chopsticks and the knife and fork:

The fork is explicit, as is the knife; its purpose is to spear the food; it is shaped accordingly. The purpose of the knife is to cut the food, and it is shaped for that. However, the function of chopsticks is ambiguous. With them you can cut, lift, spear, and separate. Differentiation lies in the movement of the hand.

He muses on what this says about Chinese thought and Chinese foreign policy: “Differentiations on the Chinese side are not explicit, and are missed if one expects Western ways.”

The Chinese language becomes “tyrant, mistress and illusionist at the same time.” Terrill learned to speak hundreds of words that he couldn’t remember how to write: “I copied each damn ideograph onto a ‘flash card,’ and carried the pack of square white cards around Harvard campus, like a thief bearing the code of a safe he hoped to crack.”

Whitlam shared Terrill’s passion, respecting the traditions, rationality and humour of Chinese people. “In many years of association with him,” writes Terrill, “Chinese were the only living people I ever saw him in some awe of (he esteemed the ancient Greeks and Romans).”

Whitlam’s effort to go to China in 1971 was risky, as Terrill writes: “Whitlam announced his appeal to Beijing for a visit before he telephoned me to try to make the invitation occur! He seemed more confident than I was that I could pull a few strings.” When the Beijing invitation is issued, Whitlam sends a cable to Terrill that reads simply, “Eureka. We won.”

Whitlam, he observes, had the “rationality of a bright lawyer; he wanted a logical, solve-all-the-problems Australian foreign policy.” Terrill quotes a 1967 view that Australia was dependent on the United States for its defence, Europe for its culture, and Japan and China for its markets, observing, “Whitlam wanted to tie all three strands together into one package.”

Overall, Terrill says, Mao and Zhou saw Australia in the context of its British heritage and American links — not, as Whitlam did, as a country within Asia. He quotes this exchange between Mao and Whitlam:

Mao asked, “Would your Labor Party dare to make revolution?”

“We stand for evolution rather than revolution,” said Whitlam, using a formulation I had often heard from him.

Mao: “That sounds like the theories of Charles Darwin?”

“I feel Darwin’s ideas relate to fauna and flora rather than to social development,” suggested Whitlam.

Having been the right man for the moment for Whitlam, Terrill played some of the same role for his teacher at Harvard, Henry Kissinger.

Waiting in Beijing for Whitlam to arrive in 1971, Terrill is puzzled that the Chinese are so interested in quizzing him about Kissinger, who by this time was national security advisor to President Richard Nixon. At the same moment, Kissinger himself was about to arrive in Beijing for a secret visit. He would later comment on Zhou Enlai’s “stunning” knowledge of his background.

Terrill, a man of the left, admired the realist clarity of Kissinger’s focus on US interests:

I found a striking virtue in Kissinger’s open mind about China. “What should we talk to the Chinese about?” he would ask me, a totally different approach from the more usual, “When are the Chinese going to become worthy of our recognising them?” An understanding of balance of power politics also made Kissinger a refreshing force in American policy toward Asia. He saw that China and America had a mutual interest in drawing closer to each other as a way of countering Soviet power. He felt the breakthrough with the Chinese would come on broad grounds and he was correct.

Terrill saw in Nixon’s 1972 trip to China the American capacity for renewal and enthusiasm. Nixon’s shift turned a bipolar world into a triangle, he writes, ushering in the age of economics in East Asia. The American market was the catalyst and the Chinese economy was the beneficiary. As America had gone to the moon, Nixon had gone to Beijing.

“Nixon eventually said his trip added up to ‘a week that changed the world,’” he writes. “As summit meetings go, the trip did indeed change the world. China emerged with a half-reassuring smile from the Cultural Revolution, triangular diplomacy was born, the Russians were agitated like ants on a hot stove, and most of the domestic critics of both Zhou Enlai and Nixon were (for the moment) silenced.”

When Mao died in 1976, Terrill recorded some positive thoughts about the chairman in his diary: “His early idea of rooting thought in observed reality. Of a leader keeping his compass on ordinary people’s needs. Of taking the long view. Of holding to a poet’s whimsy amidst griding struggle.”

Terrill devotes a chapter to what Chinese friends later told him about the turmoil and suffering of the Cultural Revolution. His biography of Mao, published in 1980, describes Mao as “discontented, militant, whimsical and anti-Soviet,” responding to complexities by blaming class enemies.

Mao was in a race against time for the Chinese Revolution, and for himself, Terrill reflects: “[H]e sought quick renewal at once political and personal. A semi-Daoist trait of questioning even his own successes seemed to surface within Mao. The ‘monkey’ in him got the better of the ‘tiger.’”

Terrill judges that Mao unified and strengthened China, but he did not change human nature, nor “cancel the sense of honour, taste for materialism, and family-mindedness of the Chinese people.”

When Terrill’s New York publisher gives a visiting delegation of Chinese publishers one of the first copies of Terrill’s Mao, “they handled it like a hand grenade.” Eventually, Mao “was published in the PRC in Chinese and, to the surprise of author, publisher, and a nervous but cooperative Chinese government” became a bestseller.

Much was made possible because of the “stunning recovery” of Deng Xiaoping, “the chain-smoke Cultural Revolution victim” whose return to power delivered huge changes in China’s policy. Terrill marks the consequent shift in the views expressed by a senior Chinese diplomat. In the mid 1970s, the diplomat praised turmoil and talked about international class struggle; after a lunch in 1981, Terrill noted, “He sounded like a blend of Bismarck and an overseas Chinese businessman.”

Under Deng, China “weighed the balance of power, counted its foreign aid pennies, and tackled the unmodernised condition of its own armies. China was buying time, coping cleverly with the gap between ambitions and capacity. Its top priority was economic development at home.”

Lee Kuan Yew tells Terrill that Deng had told him in a conversation, “Marxism has failed in China.” Tragic as the Cultural Revolution was, it became a springboard for Deng to leap without qualms towards fresh thinking, Terrill reflects:

Deng Xiaoping tried to save communism with one hand and bury it with the other. He built a China economically minded at home and nationalistic abroad. His way was to achieve a desired result without regard to image, theory, or elegance of method. He never was a diligent reader or given to philosophising, but he displayed a knack for knowing what to do and what not to say. He once described his political style: “I cross the river by touching my feet against the stones, this one and that one, to keep my balance and get to the other side.”

As China opened up for its own people in the 1980s, Terrill feels the dualism that will deliver tragedy in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Here, as in much of the book, the story is driven by conversations with Chinese friends and contacts who embrace new opportunities but are sceptical about China without the Communist Party at the helm. Their ambivalence isn’t hard to explain: “the revolution set in place a Leninist political system, while reform sought a commodity economy — the two don’t mix.”

Australian Bush to Tiananmen Square concludes with the Tiananmen bloodshed. Terrill heads that final chapter “Epilogue,” and it is an epilogue, too, for a moment of hope.

Terrill was on the streets of Beijing when the tanks crushed the democracy demonstrations on 4 June 1989. His account is that of a historian with the eye of an on-the-ground reporter:

That night, despite the horrors, my view of the capacities of Chinese people was enhanced. The courage, humour, practicality, and sense of history of youth whom I talked with intensified my faith in the Chinese. Yet I also felt that the courage of the crowd was almost suicidal, for Communists when their grip on power is threatened have a strong tendency to behave like Communists.

A life devoted to going deep into China has taught Terrill much about what the party will do to its own people. He records the words one woman cried to him near Tiananmen on June 4: “Tell the world our government has gone mad.”

The boy from Bruthen was drawn to the exotic, but he judges that China’s exoticism is breaking down before the universals of the human condition. “I do not think individualism and political pluralism will come to China from the West,” he writes. “The demand for them will burst out within China, not as a diktat from a father-figure from on high but as people express themselves politically, grabbed from below.”

As a man who has written much in his lifetime, Terrill doesn’t need to cram everything in to this elegant work. Much that has already been written can be omitted. That body of work has some standout pieces. His 1972 book 800,000,000: The Real China was one of the Asia works of the 1970s — a Penguin edition usually sat near a pile of the weekly edition of the Far Eastern Economic Review.

The Chinese-language edition of Mao has sold 1.5 million copies. Terrill’s 2003 book, The New Chinese Empire: And What It Means for the World, is a deep meditation on the meaning of China, wedded to an optimism that the country will eventually produce a modern democratic state.

The oeuvre of the boy from the bush also has some wattle and eucalyptus, particularly the 1987 The Australians, reworked in 2000 as The Australians: The Way We Live Now. For an Australian-flavoured dive into Terrill land, download (free) his 2006 paper Riding the Wave: The Rise of China and Options for Australian Policy and from 2013, Facing the dragon: China Policy In a New Era.

The personal summing up of the memoir comes in the penultimate chapter, before the Tiananmen epilogue. “Am I married to China?” Terrill asks at its conclusion. “Sometimes, I feel China has conquered me, and taken control of my days as a would-be expert on China. Of course, that would be nothing, compared with China taking control of the West. Momentous challenges and benefits beckoned for both sides as the fateful year of 1989 unfolded. Knowing the past did not guarantee knowing China’s future. Still, it was a stirring life experience for a boy from the Australian Bush.” •