The Trial of Sören Qvist

By Janet Lewis | Swallow Press | $22.99

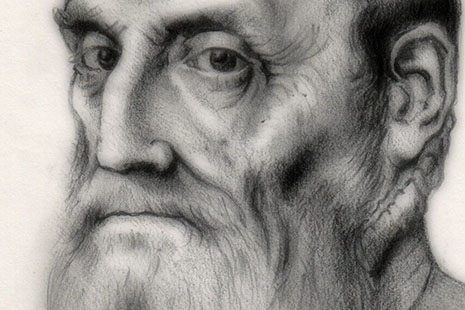

FOR a writer in search of a plot, it is hard to go past a criminal or political trial, with all its inherent drama, the accumulation of evidence and counter-evidence, the piecing together of cause and effect, of actions and consequences. Further layers can be added to the plot if the charges are fabricated and the verdict tainted, as they are in The Trial of Sören Qvist (1947), the American poet and novelist Janet Lewis’s reimagining of a trial for murder that took place in Denmark in 1626. Janet Lewis, who died in 1998, in her hundredth year, was known in her lifetime primarily as a poet, and to many of her admirers that is probably still the case today, yet this book – together with two other novels to which collectively she gave the title Cases of Circumstantial Evidence – reveal her equivalent gifts as a novelist and, in a quietly prescient way, capture our contemporary fascination with questions of identity and impersonation.

The Trial of Sören Qvist, recently reissued by Swallow Press, is based on actual events as conveyed by surviving records and in accounts written many years afterwards. It explores the ways in which the normally distinct qualities of guilt and responsibility can, under certain circumstances, slowly elide into one another and become indistinguishable. Sören Qvist, an innocent man accused of murder by a malevolent neighbour, at first resolutely defends himself against the charge but, over time, comes to believe in the circumstantial evidence arrayed against him, and to find himself not only responsible for certain of the incidents and actions that led to the murder, but guilty of the murder itself, the one being impossible to separate in his mind from the other.

The description of this murder and the trial that provided Janet Lewis with the inspiration for her novel came from a volume compiled and written by the nineteenth century legal writer Samuel March Phillipps, who had an eye for the intriguing and unusual among the records of criminal trials from the near and distant past. In his Famous Cases of Circumstantial Evidence; with an Introduction on the Theory of Presumptive Proof, Phillipps declares the detention, trial and execution of Sören Qvist to be the “most striking” of all the cases he describes, not least because “the testimony was altogether fabricated by his accuser.” Phillipps’s summary of the fall of Sören Qvist, pastor of Vejlby in Jutland in the early part of the seventeenth century, has all the ingredients of a classic tale of revenge (ingredients that the Danish writer Steen Steensen Bilcher used as the basis for his novella The Parson of Vejlby (1829), a work often credited as being among the first of modern crime novels.)

It is hardly surprising that the sufferings of Sören Qvist have, in the manner of other, more widely known instances of false or trumped-up accusations, guilty verdicts, and later vindications – the trials of Joan of Arc, for example, or Alfred Dreyfus – been recounted many times and in many forms. What Lewis brings to this particular retelling is a cool eye for the way in which Sören Qvist comes to recognise, in the face of the vengeful hatred directed towards him, that he has by his very nature helped to bring his fate upon himself, that if he has not committed the particular offence of which he is accused then he has escaped committing similar offences only by good fortune and the grace of God. Qvist is compelled to draw lessons from his own predicament, because to see it as essentially random and meaningless – a piece of very bad luck – is more than he can contemplate. “He is one of a great company of men and women,” says Lewis in her preface to the original edition, “who have preferred to lose their lives rather than accept a universe without plan or without meaning.”

Samuel March Phillipps’s version of the tale presents the parson and his nemesis – a local landowner called Morten Bruus – as direct opposites. Qvist, says Phillipps, “was a man of excellent moral character, generous, hospitable, and diligent in the performance of his sacred duties.” Bruus, by contrast, was “a self-seeker” and “an oppressor of the poor.” But Phillipps also acknowledges one defect in the good pastor, and it is this defect that drives the action on and seals his fate. “He was also a man of constitutionally violent temper.” Lewis makes much of this characteristic, having Qvist recall the reckless fighting of a duel in his youth, in which he could so easily have killed his opponent. And displaying a mid-century fascination with the roots of psychological motivation, she has Qvist hark back to an incident from his childhood, in which he killed his beloved dog in a fit of temper.

When Qvist angrily rejects Morten Bruus as a suitor for his daughter Anna, Bruus devises a scheme that capitalises on his enemy’s weakness, and turns his temper against him. He insinuates his lazy and impertinent brother Niels into the pastor’s household as a servant, and encourages him to provoke the pastor and to test his charitable principles to the limit. When the pastor reaches the point of ungovernable rage he beats Niels with a spade, and even thinks for a moment that he has killed him, before Niels jumps up and runs away, not to be seen in Vejlby again for another twenty years. Morten Bruus has in fact bribed his brother to disappear, but not before obliging him to exchange clothes with the body of a man who has recently committed suicide, turning the dead man into his brother, a victim of Sören Qvist’s murderous anger.

The Trial of Sören Qvist is the second of the three novels that Janet Lewis wrote under the rubric of Cases of Circumstantial Evidence. The third in the series, The Ghost of Monsieur Scarron, is based on a complex case from the late seventeenth century, in Paris, that remains little-known today, but the first, The Wife of Martin Guerre (1941), was one of the key sources for the popular 1982 film starring Gerard Depardieu. The film, together with the historian Natalie Zemon Davis’ influential account, The Return of Martin Guerre (1983), to say nothing of a long list of versions based on versions, has helped to transform the surviving historical records of this case into the quintessential tale, for modern audiences, of impersonation and unmasking.

In The Wife of Martin Guerre, as in all the retellings, the false Martin Guerre is a central character, very much alive until the end. But in The Trial of Sören Qvist – which, like The Wife of Martin Guerre, hinges on the consequences of impersonation – the impersonator is dead when we meet him, and we never learn his name. The dead body, dug up and dressed up by Morten Bruus to be posed, in a freshly dug grave, as his brother Niels, is merely the catalyst that leads Sören Qvist to question his own identity and his understanding of himself, to question, in effect, the extent to which he is acting the role of kindly and devout pastor. All this is told by Lewis in clear and limpid prose, set in a world in which nature – and one’s true nature – is inescapable. The natural world behaves simply and instinctively – “the candle flames steadied themselves,” “the leaves had spread themselves” – but human nature is more complicated and more inclined to deceive itself and others. When Niels Bruus, supposedly dead, returns to Weibly, two decades after the trial and execution of Sören Qvist, he is challenged over his true identity. “It is a serious matter,” he is warned, “to represent yourself as someone other than you are.” •