It is fifty years since Labor’s national executive last intervened in the affairs of the party’s Victorian branch — and during that time the state has become the party’s best electoral performer. If the experience of half a century ago is any guide, the consequences of this week’s branch-staking revelations could be very significant indeed.

Back then, Labor’s Victorian branch was tightly controlled by the left. The bitter fight over alleged communist influence in the party, which had caused the disastrous Labor split of 1955, was still raging. The breakaway group, the Democratic Labor Party, or DLP, had captured a small but decisive share of the vote, its preferences shoring up the Coalition’s performance at state and federal elections.

In Victoria, premier Henry Bolte’s Liberals remained firmly in control, as they had since 1955. Federally, the Coalition was twenty years into the longest unbroken run in government by any party. Labor’s protracted spell in the wilderness marked the lowest ebb in the party’s history.

A major problem for Labor had been the loss to the DLP of large sections of its traditional Catholic vote. The wily Bob Menzies, Liberal prime minister since 1949, had gained the support of many Catholics with a program of state aid for Catholic schools, initially aimed at providing science-teaching facilities but later broadened to include general funding.

Labor’s left — especially influential in Victoria — remained resolutely opposed to state aid, seeing it as capitulation to B.A. Santamaria’s Catholic Social Studies Movement (known simply as “the Movement”), which it believed had provoked the party split. When opposition to state aid was reaffirmed at a crucial national conference in 1965, it became clear that Labor was dividing between traditionalists/ideologues and modernisers/pragmatists. The conference decision also stymied back-channel efforts to mend the split, as was confirmed for me years later by both Santamaria and Gough Whitlam, who was deputy leader at the time.

Whitlam — in his characteristic “crash through or crash” style — was engaged in a running war with the left-dominated national executive, whose members he described as “witless men.” Campaigning in a by-election in 1966, he stepped up his attack, issuing a statement criticising the “extremist controlling group” for using the party “as a vehicle for their own prejudice and vengeance.” Unless the party embarked on urgent structural reform, he added, it risked being reduced to “a sectional rump.” He only narrowly averted expulsion from the party.

Once he wrested the leadership from the veteran Arthur Calwell in 1967, Whitlam turned to what he saw as the epicentre of the party’s problems, the left’s Victorian stronghold. He was convinced that significant change in the branch was necessary if the party was to improve its dismal performance at the polls. The expected resistance emerged immediately. Calwell formally charged him with disloyalty and unworthy conduct after Whitlam had accused him of “debauching” the debate on the Vietnam war; the executive found against Whitlam and he was reprimanded.

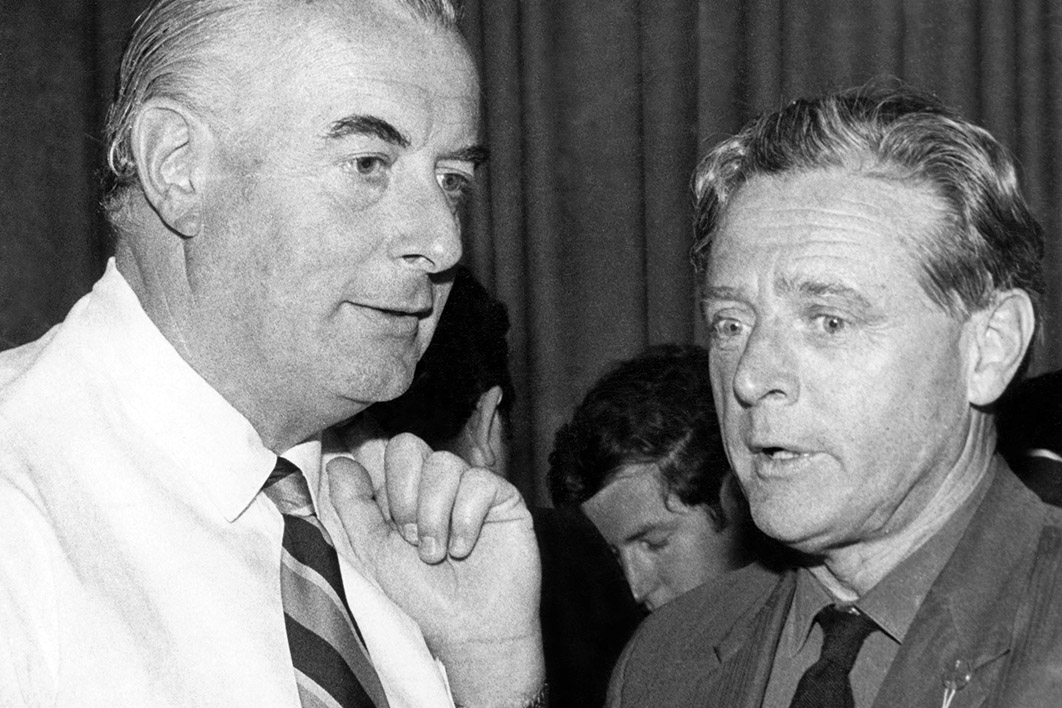

Incensed, Whitlam resigned his leadership in order to recontest and win a mandate to pursue reform in Victoria. In the subsequent leadership ballot he was opposed by a Victorian left-winger, Jim Cairns, who posed the question to fellow party members: “Whose party is this — ours or his?” The members weren’t of a single mind on the question, and Whitlam scraped in by an uncomfortably narrow thirty-eight votes to thirty-two.

While Whitlam succeeded in pushing for the party’s parliamentary leaders to sit on the national executive and for a softening of its opposition to state aid, the problems in Victoria persisted. His sense of frustration was compounded when Labor made significant gains at the 1969 federal election, winning 47 per cent of the national vote, but managed just 41.3 per cent in Victoria.

The bubbling tensions erupted again in Victoria in 1970. During the state election early that year, Labor leader Clyde Holding campaigned strongly on the new federal policy of state aid for non-government schools. To Holding’s amazement and embarrassment, the party’s state president, George Crawford, and secretary, Bill Hartley, both stalwarts of the left, announced in the week before the election that a Victorian Labor government would not support state aid. A furious Whitlam refused to campaign, and Holding was forced to repudiate his own policy. The Bolte government was comfortably returned.

Just months later, the issue erupted again, this time at the party’s state conference. Whitlam was censured and the party’s left dug in, but events had reached a crossroads that the party could no longer ignore, especially with the 1969 federal gains having put it within striking distance of government.

It was at this point that federal Labor decided to intervene in Victoria. National president Tom Burns and party secretary Mick Young were installed as temporary administrators pending a new power-sharing arrangement in 1971.

The intervention paid a handsome dividend when voters went to the polls in 1972. Labor significantly improved its state vote, winning 47.3 per cent in Victoria against a national figure of 49.6 per cent and helping Whitlam sweep to power. This was a sharp improvement on Victoria’s previous three federal figures: 41.3 per cent in 1969, 35 per cent in 1966 and 40.4 per cent in 1963. The party picked up three seats in Victoria, recording some of the biggest swings in the land: 10.2 per cent in La Trobe, 7.9 per cent in Holt, 7.7 per cent in Diamond Valley and 7.7 per cent in Casey. The national swing to Labor was 2.6 per cent; in Victoria it was 6 per cent.

The intervention also brought lasting cultural changes to the Victorian party. Among them was the rise of the Participants, a group mostly made up of lawyers, which became a force in the election of John Cain’s reforming Labor government in 1982 and contributed to the success of the early Hawke governments. Outstanding federal ministers including John Button and Michael Duffy had been active in the group.

The malaise in 2020 is qualitatively different: where it was a matter of factional tyranny in 1970, today it is factional subversion. And the party itself has changed enormously. It is in office in Victoria with a comfortable majority, its electoral performance is sound, and it is ably led by premier Dan Andrews, arguably the stand-out leader through the twin crises of bushfire and coronavirus.

Andrews’s prompt and deservedly brutal response to branch-stacking revelations this week had all the hallmarks of a professional hit. It remains to be seen how the party will emerge from the process he has initiated. But if 1970 is any guide, there will be changes, and they will be far-reaching. •