Daring to Hope: My Life in the 1970s

By Sheila Rowbotham | Verso | $39.99 | 326 pages

It’s a truism bordering on banality that every book is its reader. Who else besides me and other seventies feminists still alive and kicking would know about Sheila Rowbotham or who she was to us? Names like Rowbotham — or Juliet Mitchell or Shulamith Firestone or Phyllis Chesler or Dorothy Dinnerstein, to recall a mere few — are being lost in the mists of time, but within the movement itself they were far more influential than Germaine Greer, say, or Gloria Steinem, or Betty Friedan, who garnered a more popular readership.

There were reasons for this. In those halcyon days we eschewed the very notion of leaders and actively resisted the media pressure to find them. And though in time, and ironically with our success, we lost that battle, at heart we libbers never lost our collectivist fervour. That there was a dark side to that deep-seated egalitarianism for those who went on to achieve their individual ambitions is yet another aspect of the story, one that Rowbotham felt keenly.

Above all else, Daring to Hope is an exercise in what Rowbotham calls “historical memory.” Maybe all memoirs are, but not in quite the same way as this one, for me anyway. From the very first pages it was like popping some memory-enhancing pill, my mind suddenly flooded with the incredible ferment of those years. Anybody who’s seen the film Brazen Hussies will have gained an idea of how exciting and radical it all was. The consciousness-raising, the marching, the conferences, the street theatre, the abuse from right and left (and I’m talking literally here). And painful too, what with the heart-wrenching churn of intimate relationships. How we struggled to put into words and fashion theoretical sense out of what was happening.

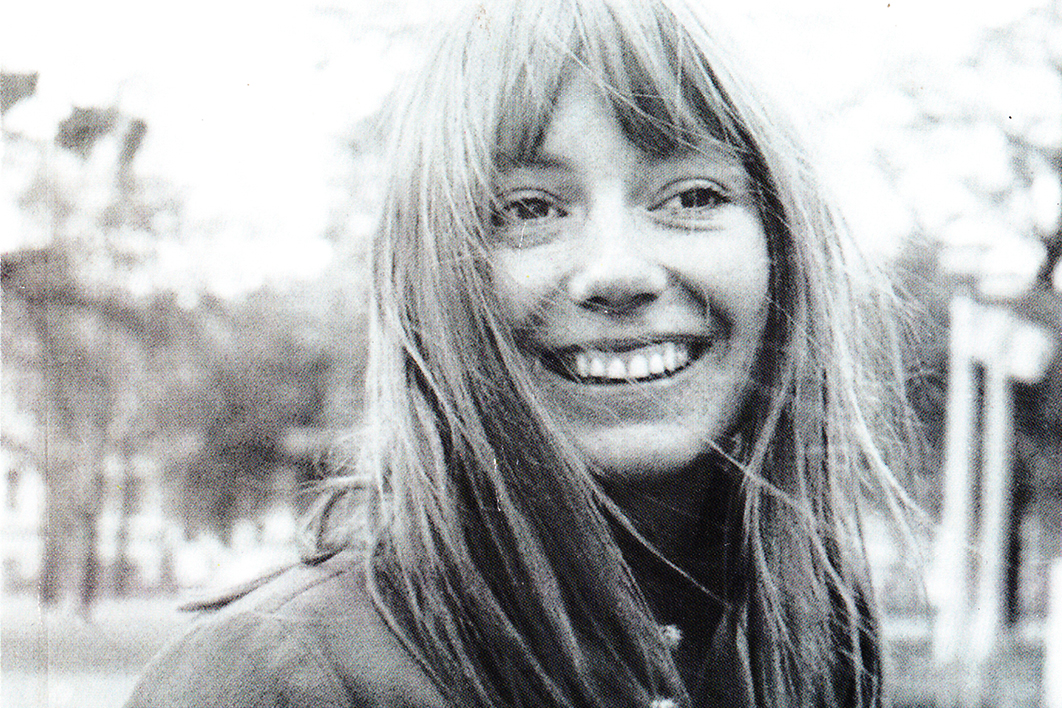

Rowbotham was one of the best of us. She wrote out of her experience in Britain, but that didn’t matter — within the Anglosphere, at least, the movement was a global one.

Her Women, Resistance and Revolution came out in 1973 and is still in print. I wouldn’t be the first to call it a classic. Take note of the title. We believed in revolution then. Juliet Mitchell’s contribution was The Longest Revolution, Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex. For if in large part women’s liberation was a child of the left, a good deal of energy was spent hoping to convince leftist males that women’s issues were legitimate ones and then, when we were successful, trying to stop them from arrogating the podiums to themselves (mansplaining being all too rife even then).

And if many of us identified as socialists — or socialist feminists as we came to call ourselves to distinguish us from “liberals” or “radicals” as the movement splintered — our aim was a socialism of an especially humane kind. On the whole we resisted dogma and championed underdogs, whether they were working-class or racial or sexual minorities or, counting us, any combination of the three. Intersectionality is what it’s called today.

But how to come up with a theory out of this? Rowbotham, it could be said, took it as her own life project, with Dorothy and Edward Thompson, doyens of left history in their day, as her mentors.

Yet Rowbotham’s work was always grounded in her activism. As groups sprang up and transmogrified across the London boroughs she managed to keep up with them and keep herself together by teaching at a comprehensive girls’ school, running Workers’ Educational Association courses and at one stage working as a doctor’s receptionist, while writing, writing, seemingly all the while. With Women, Resistance and Revolution published, the invitations to speak also came hard and fast. Where did she get the energy, I gasped, reading about it these many years later.

The fact is, she was young. We all were — I’d almost forgotten that. As she writes in her introduction:

In 1970 I was twenty-six and working on my first book. I was a socialist and part of the emerging British women’s liberation movement, supporting gay liberation, revolt in the trade unions and resistance to racism. Demands for economic and social resources and claims for recognition and respect were being asserted by many groups who had been either sidelined or outcast. The term “liberation” extended democracy beyond voting; it meant opposing all forms of inequality and hierarchy. It carried too a fragile vision of what else might be — a fusion of collective and individual freedom.

Throughout the subsequent decade the hope that gave birth to that vision met challenges at every turn, often from the many contradictory emotions that swirl to this day in our hearts. Rowbotham is appropriately candid about this, as our movement’s central insight was that the personal was indeed political. At the decade’s beginning she was more or less a free spirit, if an uncommonly hardworking one; at the end of it she was a mother of a small boy. If, in the parlance of the time, motherhood did a bit to cramp her style, it wasn’t for long, for that too was a gesture of hope. By then, too, the movement had grown beyond even our wildest imaginings.

Daring to Hope is Rowbotham’s second memoir; the first was Promise of a Dream: Remembering the Sixties, which I confess I haven’t read. Perhaps a third one about the subsequent decade or decades is in the offing, maybe not. As should be obvious now, I haven’t kept abreast of Rowbotham’s writings or indeed her life since the heady days of the 1970s. It’s as though she, like them, had been sequestered in my memory’s scrapbook, at least until now, when feminism has become a political force again. Which naturally raises the question of what went wrong in the years in between.

For one thing Maggie Thatcher happened, and Ronald Reagan. And with them a reversion to the crude laissez-faire capitalism we’ve come to know as neoliberalism — a cultural as well as an economic phenomenon during which second-wave-type feminism was repudiated along with any notion of collectivism. “The new amalgam of right-wing politics Thatcher came to embody,” Rowbotham writes, congealed into “a mindset… undermining the hopes of social equality and of extending democracy into daily life.” And look where it has gotten us.

But I would be the last to suggest that there will never be another time like the seventies. For all I know, as a woman in my eighties and captive to reminiscence, the ferment may be bubbling again right now. Certainly, there are signs. It’s never quite the same — history doesn’t work like that — yet women’s history has been noted for its cyclical nature. There’s #MeToo, and the rising anger over the appalling incidence of domestic abuse, the bullying of women in political life and on social media, the widening gender pay gap, the increasing homelessness of women in their fifties, and much else. Suddenly, feminism is no longer the dirty word it became in the intervening decades. And if by socialism we mean a genuine democracy, in which a nation’s wealth is more equitably distributed and societies are more than their economies, I see shoots growing there too. •