MOST women members of the Australian Defence Force will not experience sustained frontline combat duty any more than do most male members of the military. So, in practical terms, there is probably less than meets the eye to the federal government’s decision to allow women to serve in all combat roles within five years.

But in terms of defence force equity it is a notable advance. It removes another vestige of discrimination against the presumably few ADF women who want to be frontline infantry fighters and who can demonstrate the required skills to do so.

The decision means that no combat roles will any longer be closed to women just because they are women. There may be other good reasons to exclude individuals from specific roles, but they will not automatically include gender, and that is no bad thing given the sometimes appallingly unequal treatment endured by women in the military.

To its credit, federal cabinet is moving cautiously by introducing the change over five years to enable training programs to be developed for women who want to take up infantry combat roles. The five-year phase-in will also reveal how many women want these onerous jobs and what percentage of them are likely to be physically capable of doing the work.

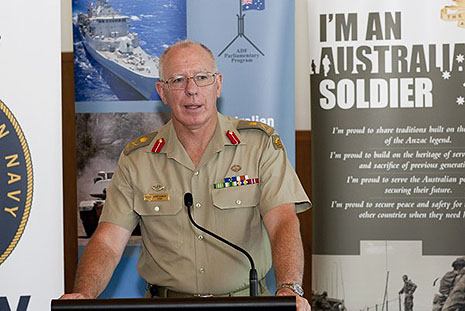

It is hardly surprising, as defence force chief Major General David Hurley says, that there will be mixed reactions within the ADF. But the important issue is not how many women eventually assume these combat roles. It is that the government has opened up the last 7 per cent of military positions from which women have been excluded solely on the basis of their gender. That reflects progress and the ADF’s need to maintain adequate numbers of front-line troops.

The decision has provoked a predictable response from the Australia Defence Association, or ADA, and its spokesman, former Lieutenant Colonel Neil James. Reflecting and pandering to prejudices and Rum Corps attitudes in some army circles, James has attracted media attention by harrumphing that the government’s decision will increase the risk of “disproportionate” female battlefield casualties.

James has branded defenders of the government’s decision idealists, ideologues and theorists who do not appreciate the horrors of frontline combat and the bio-mechanical differences between men and women. The ADA alone is clear-headed and logical; all others are sloppy thinkers.

While Mr James frequently criticises the journalists to whom he seeks to peddle his words of wisdom, and has little time for civilian judgement on any defence policy issues, his analysis of the decision to open frontline combat roles to women has its own flaws and fatuities.

First, he does not explain his claim that female battlefield casualties will be “disproportionate.” Disproportionate to what? To the total number of ADF members? To the total number of women in the ADF? To the total number of infantry personnel in the ADF?

An ADA policy statement suggests female infantry casualties are likely to be disproportionate to male casualties “chiefly because they would be exposed to higher risks over time” than men doing the same job. The ADA believes the risks would be higher because most women eventually would probably lose intense person-to-person physical confrontations in prolonged direct combat. This sounds suspiciously like “the weaker sex” argument; it takes no account of leadership, professionalism, motivation, esprit de corps, training and equipment or the capability of opposing forces.

Second, James does not explain the basis for the ADA view. How can he know female casualties will be disproportionate before it is clear how many women will eventually take part in intense combat? It is possible, indeed likely, that the numbers will be so low that it will not make much sense to talk about disproportionate casualties.

Thirdly, and most interestingly, James’s complaint reflects the confused ADA policy on women in combat – a policy that is apparently the product of his own intellectual exertions and his very apparent dislike of the journalists on whom he relies to report his views.

As noted, it is essentially a “weaker sex” argument hiding behind a façade of acceptance of the fact that women already perform many frontline combat tasks in the navy, air force and army. The ADA essentially believes women can be employed in combat roles where “force is applied from a distance” but that they should not be expected to fight enemy male soldiers “continually in a person-to-person physical sense and as a permanent and core part of their job.”

But obviously there are dangers in both distant and close quarters combat. To join the ADF is to accept the risk of death or injury. What makes the difference in modern high-tech warfare has less to do with gender than with the training, equipment and attitude of the rival combatants.

The ADA says it supports the right of individual women to choose whether to accept combat risks. But it also says “the exercise of such choice needs careful monitoring to ensure it is truly free and reasonable.” But monitoring by whom? And what sort of criteria would satisfy “truly free and reasonable” in these circumstances?

For a man who claims a monopoly on truth and objectivity, Neil James has a lot more thinking to do before he mounts a convincing case against eliminating gender inequity in the ADF. •