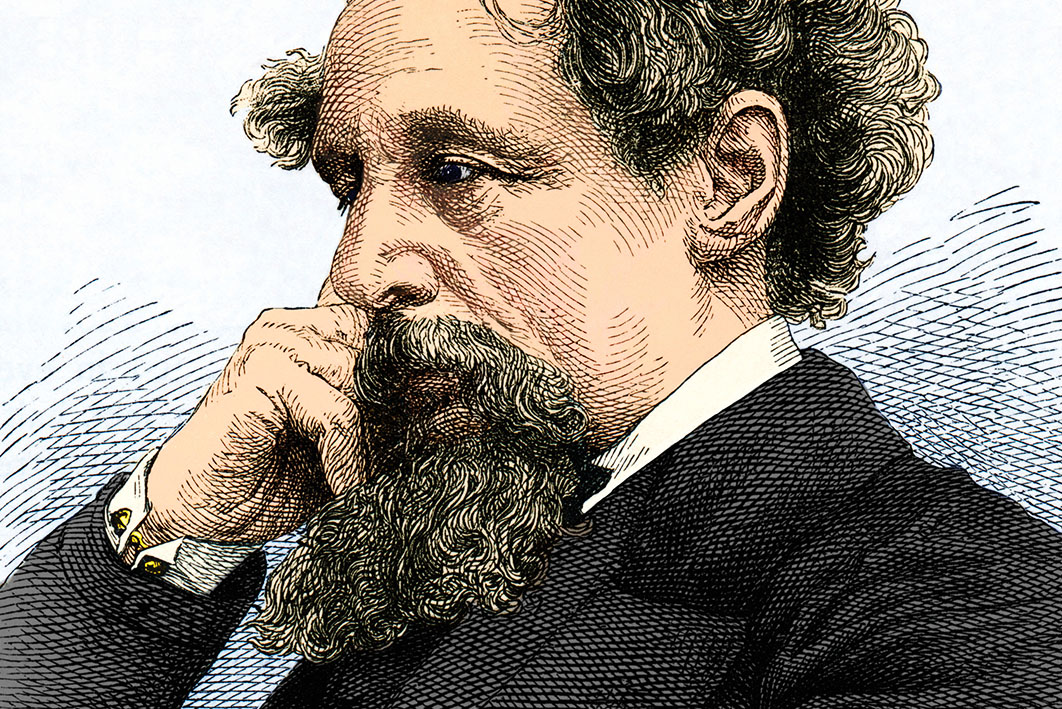

Charles Dickens: A Life

By Claire Tomalin | Viking | $39.95

The Other Dickens: A Life of Catherine Hogarth

By Lillian Nayder | Cornell University Press | $49.95

Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist

By Robert Douglas-Fairhurst | Harvard University Press | $39.95

The 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Dickens falls on 7 February 2012 and the celebrations have already begun. The Morgan Library and Museum’s “Dickens at 200” exhibition, drawing on its vast collection of Dickens-related material, has opened in New York and runs until just after the big day. Further major exhibitions are planned, including one at the Strauhof Literary Museum in Zurich and several in France, a country Dickens admired and visited often. The British Film Institute is holding a three-month retrospective, beginning in January, of the vast array of screen adaptations of his work, even as further adaptations are in production for release later next year.

The British Council, meanwhile, noting the continuing and ever-renewing affinity felt by many people around the world for Dickens’s work and legacy, “will coordinate a worldwide call for aspiring writers, illustrators and photographers to respond to their city,” with Dickens’s “Sketches of London” as their inspiration. The official “Dickens 2012” website lists these and many other forthcoming events on its calendar, ranging from a special iteration of the annual Dickens Festival in Deventer in the Netherlands (at which, intriguingly, “the organisers are planning to break several world records and introduce acrobatic elements”) to a “Dickens half-marathon” in Texas, scheduled to be run in June.

The link between Dickens and a half-marathon named in his honour is not as tenuous as it may first appear. Claire Tomalin’s splendid Charles Dickens: A Life, announced recently as the Daily Telegraph Biography of the Year, captures the intense physicality of the man, and the ways in which exercise, particularly long walks, would both calm and stimulate his restless imagination. His obsessive, youthful love for Maria Beadnell – “I never loved and I never can love any human creature breathing but yourself” – would have him walking, in the early hours of the morning, from his work as a reporter at the House of Commons to Maria’s home in Lombard Street, where he would wander past while imagining her asleep in her bedroom. Tomalin traces his likely route, noting that “it must have taken two hours and got him home not much before morning.”

Years later, when his marriage to Catherine Hogarth was disintegrating and, to the dismay of many then and now, he was furiously writing her out of his life, he temporarily escaped the tension all around by walking from his city to his country home, from Tavistock House to Gad’s Hill – “a good thirty miles” notes Tomalin, an impressive distance for someone whose health, never robust, was proving increasingly troublesome.

Like all biographers, particularly those whose subjects are long dead, Tomalin depends for her understanding of Dickens’s life on what is on the record, on what, by a combination of chance and intention, has survived to tell the tale. She is aware of how these surviving records, on which many preceding Dickens biographies – including her own award-winning study The Invisible Woman: The Story of Charles Dickens and Nelly Ternan (1990) – have been based, must be approached with a fresh and even sceptical eye if another Life is to be justified. “As to the colour of Dickens’s eyes,” she says in an elegant reference to the sometimes contradictory nature of biographical sources, “they were reported variously as dark brown, dark glittering black, clear blue, ‘not blue,’ distinct clear hazel, ‘large effeminate eyes,’ clear grey, green-grey, dark slaty blue…,” adding in a footnote that she has “collected more variants.” Tomalin does not venture a definitive opinion on which, if any, is correct.

In other instances, however, particularly in respect of Dickens’s relationships with women – his mother, his first love Maria Beadnell, his wife Catherine and her sisters, the actress Nelly Ternan and her sisters, not to mention their fictional counterparts – she weighs up the evidence in the light of what is possible or likely and produces convincing readings of them all. To put it at its gentlest, these readings do not always flatter Dickens. Yet Tomalin never loses sympathy for her subject, even as she acknowledges that sometimes it is hard not to turn away, particularly from his ruthless dismissal of Catherine, his wife of more than twenty years and mother of their ten children, in favour of starting a completely new story.

CATHERINE died in 1879, almost a decade after Dickens. And yet, as Lillian Nayder points out in The Other Dickens: A Life of Catherine Hogarth, it has often been assumed that she died shortly after her estranged husband, or else that she lingered on in the half-light to which she had long been consigned, her life effectively over even before his. Nayder goes to great pains to restore the balance, to “pluck her,” as she rather dramatically puts it, “from the flames of her husband’s funeral pyre.” Nayder evokes what it might have been like to be a, rather than the, Dickens. She is almost certainly right to say that “Catherine’s identity as Mrs Charles Dickens did not constitute her authentic or essential self,” any more than the fact of being Dickens’s son or daughter means that there is nothing more to be said about his offspring. But there is a difference between the essential self and the part of that self that survives in biographical form; there are few among Dickens’s family and close friends who live on independently of their association with him, or whose own achievements outshine the simple fact that they knew him, and he knew them. Catherine herself was more than aware of what constituted any claim she might have to be remembered; as Nayder notes in her afterword, she requested that her letters from her husband be preserved, that “the world may know that he loved me once.”

Tomalin is particularly strong on this aspect of biography, on the ways in which other lives are subsumed within, and draw their significance from, the lead player. She quotes John Forster, Dickens’s greatest friend and his chosen biographer; a busy and successful man in his own right, Forster nevertheless saw Dickens’s death as meaning that “nothing in future can, to me, ever again be as it was. The duties of life remain while life remains, but for me the joy of it is gone forever more.” For Dickens’s sister-in-law Georgina Hogarth, who chose to continue on as his housekeeper after the end of his marriage, and to take his part against her sister, nothing would “ever fill up that empty place.” There is much more here than the exaggerations of conventional sentiment. For John Forster and Georgina Hogarth, as for many others who went on living after his death, the remainder of their time would be devoted to celebrating, whether publicly or privately, the man who had, in one sense or another, created them. Tomalin quotes George Dolby – the canny businessman who managed Dickens’s gruelling schedule of readings in his last years and remained loyal to his memory – crediting his friend and employer, by way of an appropriately literary metaphor, with giving him “the brightest chapter of my life.”

Dickens, writes Tomalin, “was surrounded by dependants”: his parents and siblings, his own children, and particularly his six sons for whom, with the exception of Henry, things never seemed to go quite right; and beyond his family, the various people for whom on frequent occasions he felt a sense of responsibility which translated into financial help and other acts of generosity. Behind this selflessness lay a very clear vision of what might have been, of how things could very well have turned out differently for him. Tomalin introduces this theme early on when she refers to some early pieces written by Dickens, “deadpan accounts of respectable failures and victims of London.” These sketches, she suggests, act as “emblematic warnings” of how easily a life can go wrong, and how quickly the prospect of success can slip away. Later, in describing the father’s disappointment in his sons, she speculates that “he saw them as a long line of versions of himself that had come out badly.” This notion, of shadow or alternative lives forever in the frame, commenting by their presence on the role of chance and the precariousness of things, gives Tomalin’s book, although in some ways quite conventionally structured, a very contemporary tinge.

EVEN more contemporary in feel is Robert Douglas-Fairhurst’s Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist, another biographical study that comes in good time for the celebrations. Douglas-Fairhurst focuses on Dickens’s early life and career, when he was becoming but was not yet made. He makes a similar point to Tomalin’s about the early sketches, published when Dickens wrote as “Boz,” identifying the strand that links them together as “the ease with which lives can be stymied or knocked off course.” He takes this relatively straightforward notion, that there is always the possibility that things will take a turn for the worse, and uses it to brilliantly illuminate the life, the work, and the relationship between the two. The idea that life is a series of “becomings,” with that word’s double suggestion of both acting and being acted upon, is presented by Tomalin and Douglas-Fairhurst – each, for example, has a chapter entitled “Becoming Boz” – but for Douglas-Fairhurst it is at the very centre of his argument.

Douglas-Fairhurst makes much of Dickens’s plurality, of the idea that his life was in fact a series of lives, some contradictory yet fully realised, others merely hints of what might have been. “There is almost nothing one can say about him,” he writes, “of which the opposite is not also true.” Douglas-Fairhurst’s sharp-eyed familiarity with the works brings to light a wealth of examples of Dickens’s fascination with alternative lives and the role of chance. “The things that never happen,” he quotes from David Copperfield, “are often as much realities to us, in their effects, as those that are accomplished.”

Dickens’s awareness of how differently things might have gone for him – “I might have been… a little robber” – informs all his writing, but none more so than Oliver Twist, which he wrote rather as he lived, without quite knowing what direction he would take next. At the end of the first instalment of the novel he added that he wasn’t yet sure whether it would be “a long or a short piece of biography.” Douglas-Fairhurst characterises this line as both playful and true – “a frank acknowledgement that he didn’t yet know himself” where it was all heading. Oliver Twist, as seen through this lens, is a novel about the process of becoming, in which Dickens controls the trajectory of the plot by continually “rejecting alternative strands.” At the same time, Dickens uses that control to make clear how Oliver, in living his life, is repeatedly subject to chance. When he is about to be indentured to a chimney sweep, Oliver is saved by the fact that the magistrate, about to sign the necessary papers, cannot immediately locate his inkstand. The pause in the action creates a space in which the magistrate can reconsider. “If the inkstand had been where the old gentleman thought it was…” quotes Douglas-Fairhurst, adding, “it would have been quite a different story.”

In strikingly different ways, Tomalin and Douglas-Fairhurst convey an overriding impression of Dickens’s extraordinary energy, his capacity to keep striding on into the future, taking advantage of every opportunity, processing everything that he saw and experienced and turning it into his work. Yet all the while he was also looking backwards; “he liked,” writes Tomalin, “to keep hold of every part of his life, and relate each to the others,” thereby retrospectively converting his own life into a narrative which he repeatedly tinkered with and rewrote – in some instances, such as the story of his marriage, quite drastically. Life’s course may turn on the placement of an inkstand, but that didn’t stop Dickens (as, perhaps, it doesn’t stop many of us) trying to control his own narrative, whether he was looking forward or looking back. Both Tomalin and Douglas-Fairhurst refer to Dickens’s habit, when travelling, of rearranging the furniture in his hotel room to his liking. The props had to be correctly positioned, the scene set. And then, after imposing himself on the room, he could go to sleep. •