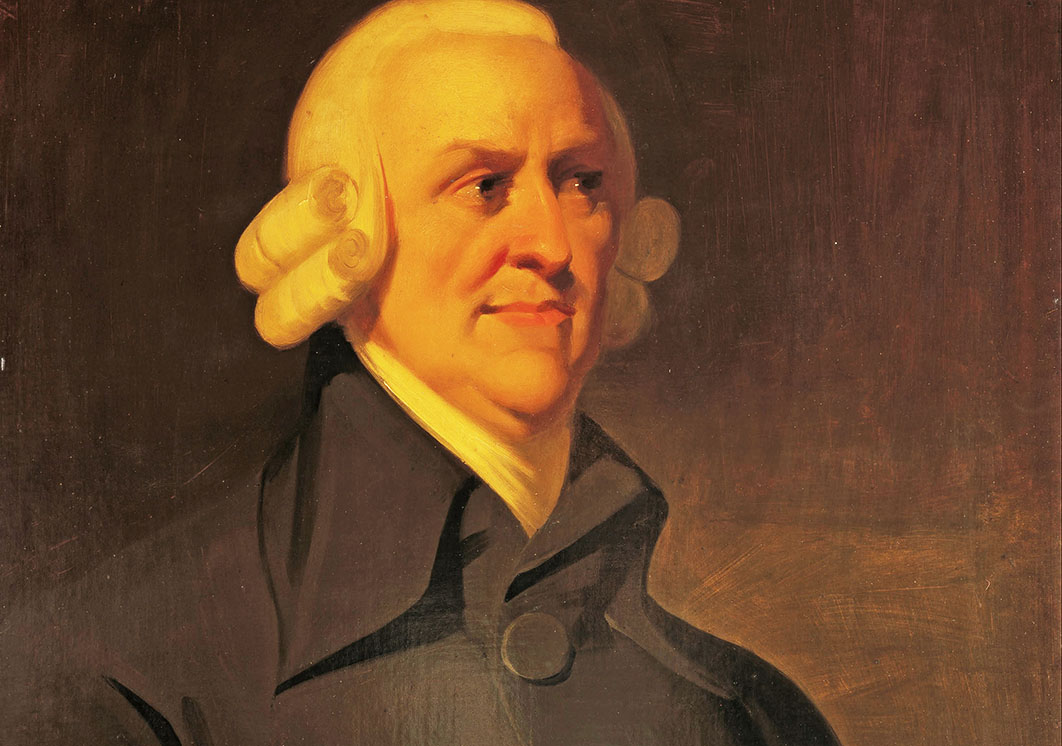

The Scottish moral philosopher and father of classical free-market economics, Adam Smith, was a strange old coot. The original absent-minded professor, he famously stumbled into a vast tanning pit on a tour of a factory because he’d become so engrossed in a discussion about free trade.

But don’t let the Buster Keaton antics fool you. Smith was a sharp observer of life, and a more nuanced thinker than many of his present-day supporters believe.

Yes, he wanted nations to achieve economic efficiency through the “invisible hand” of the market. But he also wanted them to use their wealth to behave in a civilised and thoughtful way. He wasn’t a libertarian; he could see the sense of some government intervention. He didn’t think taxation was anathema either; and he wanted the poor to be looked after. This Adam Smith would probably not have been a member of any modern-day Adam Smith Club.

He also maintained a healthy scepticism about the self-proclaimed virtues of people who run businesses. As he wrote in The Wealth of Nations, “People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices.”

In September last year Smith’s pithy assessment must have crossed the mind of Labor’s shadow assistant treasurer, former ANU economics professor Andrew Leigh, when he learnt that the chief executives of Australia’s dominant accountancy firms — EY, KPMG, Deloitte and PwC — were meeting for private dinners.

In hearings before parliament’s public accounts and audit committee, representatives of the Big Four admitted that the dinners were held once or twice a year at the head office of one of the firms. Many, many storeys up, in other words, with Sydney Harbour views and little chance of ending up in “Rear View,” the Australian Financial Review’s widely read gossip column.

In conjunction with his fellow Labor MP Julian Hill, deputy chair of the committee, Leigh wrote to the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, or ACCC, and essentially asked, WTF?

Policing anti-competitive behaviour, and proving the existence of cartels, is notoriously difficult, and there’s no evidence to suggest that illegal activity was going on at these dinners. The Big Four certainly denied anything untoward and cartel-like. “These dinners are held to discuss industry trends, both Australian and global, and cultural issues such as inclusion and diversity,” EY told the committee.

Expert opinion is mixed. Some competition lawyers say they would have advised against dining with competitors. Others are more sanguine about the exact legal position, arguing that the ACCC is unlikely to be able to prove the dinners contributed to the “lessening of competition.”

Nevertheless the ACCC duly started looking into the matter. Late last year it contacted the Awesome Foursome and requested they cough up some documents, including engagement letters, draft proposals, and other information about their public sector consultancies.

But the ACCC investigation into “Dinnerplate” — as, surely, it must be now called — is just the latest in a number of hefty hailstones raining down on the Big Four’s parade. With a federal election fast approaching, they must be concerned that Labor has been questioning why they are being paid so much money by the Coalition — as much as $1.7 billion between 2013 and 2017 — for their consultancy services.

In the wake of the Hayne royal commission, the independence of the Big Four’s expert advice has also come under greater scrutiny. Remember how the commission revealed that EY happily changed a report for insurance giant Allianz four times before it got it “right”?

After the flogging it also received from Hayne, the Australian Securities and Investment Commission is keen to muscle up. A recent ASIC report on auditing pretty much flunked the accounting industry, finding that one in five audits contained “material errors.” In plain English, they were wrong.

Just last week, parliament’s corporations and financial services committee delivered yet another nasty jab. Told by Commissioner Hayne that it too had been asleep at the wheel, the committee roused itself to call for a “serious review” of the audit market, particularly the possible conflicts of interest that arise when a company is both auditor and corporate adviser to the same entity.

The MPs bravely pointed out the obvious: “the risk… is that the big four audit firms now fail to fearlessly scrutinise the accounts and risks of the corporations that they audit because it may be detrimental to the pursuit of their wider business interests.”

Other than some admirable reporting in the Financial Review, there hasn’t been much debate in Australia about the Big Four. Perhaps there should be.

In their book, The Big Four: The Curious Past and Perilous Future of the Global Accounting Monopoly, reviewed recently in Inside Story, Ian Gow and Stuart Kells tell the unedifying story of the degradation of Big Accounting over the last several decades. These billion-dollar multinationals, Gow and Kells argue, occupy an interesting — and highly profitable — niche in the global economy. Their auditing of the world’s biggest companies keeps the market informed. But they also advise the same companies about how to make more money. At the heart of their business model lies a conflict of interest that would mightily impress a fox hired as a security consultant to a henhouse.

As the late, great Adam Smith himself might have asked, “Och, man, how long can this go on for?” •