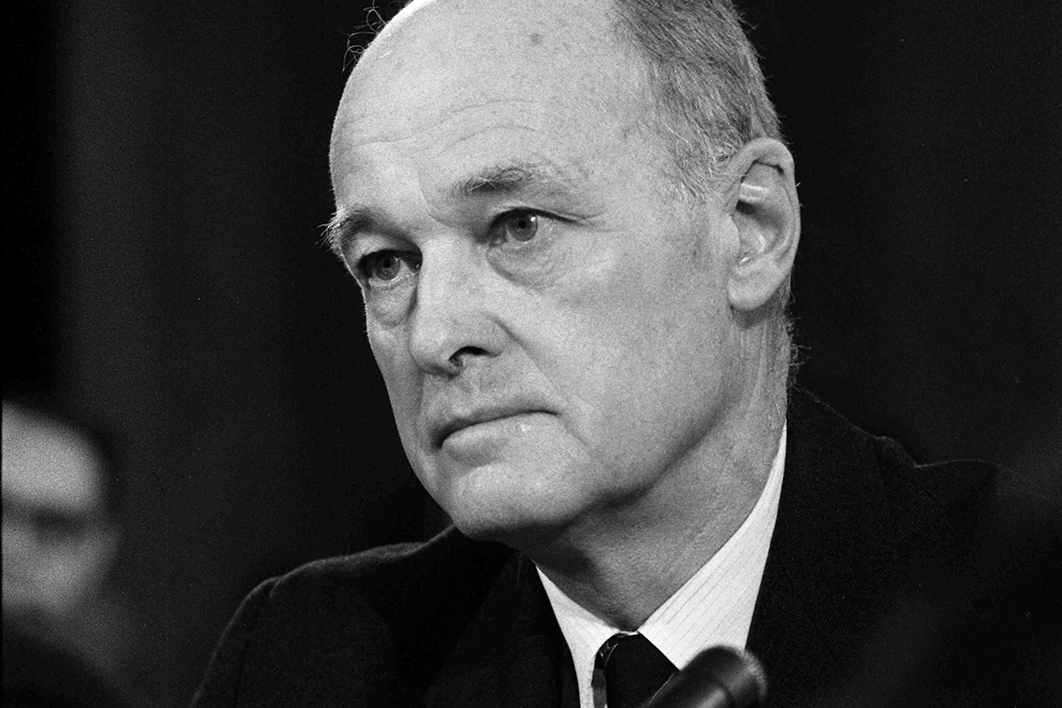

George F. Kennan: An American Life

By John Lewis Gaddis | Penguin | $56.95

JUST as the second half of the twentieth century was defined by the confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union, so the first half of this century will be framed by the contest between the United States and China.

Two “c” words – communism and containment – capture the approaches of Moscow and Washington in the forty-four-year struggle that began in 1945. No equally vivid opposition can yet be applied to the US–China contest, which flows through a broad, swirling river bounded by cooperation on one side and competition on the other. The great challenge will be to prevent the contest breaking those banks to become conflict.

The Cold War was a struggle between two separate and opposed political and economic systems; today, China is surging towards top spot in an economic world created by the United States. Washington can’t contain an economy that is a major extension of its own conceptions.

And yet the US–Soviet confrontation offers much to help us understand what we face in the coming decades. Mostly, these Cold War lessons are offered in the negative, reflecting the many ways in which the complicated dance of dependence between the United States and China differs fundamentally from the steely war-of-wills between Moscow and Washington.

One great Cold War lesson offers hope, though. For all the disastrous proxy wars, the thousands of thermonuclear weapons and the massive arms build-up, the two superpowers never went to war. Armageddon was not inevitable, despite the convictions of hardliners on both sides. To the extent that the American strategy of “containing” Soviet expansionism contributed to that outcome, it was a singular achievement, offering a less passive course than appeasement or isolationism yet never assuming that the ultimate resolution would have to wear a military uniform.

While communism was a universalist ideology bolted onto deep Russian instincts, containment was the intellectual creation of one man, George Kennan. He not only conceived it but also, over his long life, was often aghast at what others did with it – and this is one of the dynamics that drives the second half of John Lewis Gaddis’s fine new biography of the American diplomat and historian.

Gaddis, a skilled chronicler of the Cold War, has produced a magnificent account of an often troubled grand strategist, showing how messy and inexact is the task of helping to plot any nation’s international course. The book was thirty years in the making, mainly because it was not to be published until after its subject’s death, and Kennan didn’t expire until 2005 at the age of 101. Gaddis dedicates the book to Kennan’s wife, Annelise (1910–2008), with the words, “without whom it would not have been possible”; that judgement applies equally to her role in Kennan’s life.

Gaddis judges that Kennan was “by nature a pessimist,” which is no bad thing in a diplomat or strategist. So the optimism inherent in containment surely owes something to the other ways of looking at life that Annelise offered over a seventy-three-year marriage, loving and anchoring Kennan (and making sure her colour-blind husband wore matching socks). The contradictions that ran through Kennan’s work also affected their relationship, with Annelise at one point acting swiftly “to save the marriage” after she discovered one of Kennan’s affairs. In an interview when he was seventy-eight, Kennan said he still had a roving eye: “Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife. My God, I’ve coveted ten thousand of them in the course of my life, and will continue to do so on into the eighties.”

Gaddis argues that Kennan had a triangular personality, held taut by tension along each of its sides. One side was Kennan’s professionalism, first as a diplomat and then as an historian and writer. The second side was his pessimism about whether Western civilisation could survive the challenges posed by its external adversaries and internal contradictions. (In 1937 Kennan despaired at how Americans were “drugged and debilitated by automobiles and advertisements and radios and moving pictures.”) The third element was personal anguish, with Gaddis channelling his subject’s constant internal debate: “Where did he as a husband and a father and a professional and an intellectual – but also as an individual tormented by self-doubt, regretting missed opportunities – fit into all this?” This was an outstanding diplomat, subject to dark nights of the soul about everything from his work and worth to his libido, who offered his resignation from the service many times before he finally quit.

BY 1946, as the postwar order was taking shape, Kennan had spent most of his adult life in Europe. He had been an American diplomat, studied Russian, helped set up the US embassy in Moscow when diplomatic relations had been restored in 1933 (after a fifteen-year freeze) and been interned in Germany for five months when America entered the war. It was from Moscow in February 1946 that Kennan sent to Washington what became known as “the Long Telegram.” At 5000 words (not 8000, as Kennan recalled in his memoirs), it was the longest ever sent in the State Department’s long history.

On the brink of resigning and leaving Russia, Kennan saw it as a “final exasperated attempt to awaken Washington.” It worked. “After that,” Gaddis writes, “nothing in his life, or in US policy towards the Soviet Union, would be the same.”

Kennan had been on the outer with Washington since 1944, warning that US attempts to maintain and build on the wartime alliance with Moscow were doomed. During this period, Kennan was asked why he was running such a hard line about the dangers posed by a postwar Soviet Union. He replied with what turned out to be an astute forecast: “I foresee that the day will come when I will be accused of being pro-Soviet, with exactly as much vehemence as I am now accused of being anti-Soviet.”

The telegram was a triumph of timing, based on Kennan’s immersion in Russia and driven by the vivid writing skills of a man who’d aspired to be a novelist and who, in his spare time, wrote poetry to capture the essence of his thoughts as well as his emotions. For a Truman administration awaking to the harsh reality that victory in war meant the end of any shared purpose with the Soviet Union, Kennan offered clear ideas, dramatically expressed.

Paradoxically, in many respects Kennan had a far better understanding of Russia than of the United States. It is an illustration of a syndrome that besets a professional foreign service: the sophisticated diplomat who is expert at reading the pulse of the country he is studying, but has trouble hearing the heartbeat of his own nation. Stalin was one of the Russians who complimented him on the fluency and elegance of his spoken Russian.

In his analyses, Kennan was as likely to refer to Dostoyevsky as to Marx. He saw Stalin as standing in a direct line from the pre-modern tsars, showing “the same intolerance, the same dark cruelty.” Kennan described Chekhov as one of the three “fathers” who shaped his life; his religion was that of a Presbyterian much influenced by Russian Orthodoxy.

Kennan’s love of Russia made him clear-eyed about the horrors of the Soviet system. The Russian-born British philosopher Isaiah Berlin said he was “astonished” by Kennan when they met at the US embassy in Moscow after the war. “He was not at all like the people in the State Department I knew in Washington during my service there,” said Berlin. “He was more thoughtful, more austere and more melancholy than they were. He was terribly absorbed – personally involved, somehow – in the terrible nature of the [Stalin] regime, and in the convolutions of its policy.”

Although the Long Telegram didn’t use the word containment, it did present a rationale for and an outline of the new anti-Soviet policy Truman was groping towards. Kennan followed it up with an article defining the basis of containment, published anonymously in Foreign Affairs in July 1947. He argued that the main element of any US policy regarding the Soviet Union must be “a long-term, patient but firm and vigilant containment” of Russian expansive tendencies. “Soviet pressure against the free institutions of the Western world,” he wrote, “is something that can be contained by the adroit and vigilant application of counterforce at a series of constantly shifting geographical and political points, corresponding to the shifts and manoeuvres of Soviet policy, but which cannot be charmed or talked out of existence.” The identity of the author didn’t stay secret for long.

Kennan’s understanding of the problem confronting the United States, his prescription and his role in the creation of the Marshall plan to rebuild Europe’s shattered economies made him one of the creators of the new international system. In Gaddis’s view, Kennan’s strategy was more robust than his own faith in it. It offered the West a way out, “a path between the appeasement that had failed to prevent World War 2 and the alternative of a third world war, the devastation from which would have been unimaginable.” For Henry Kissinger, Kennan “came as close to authoring the diplomatic doctrine of his era as any diplomat in history.”

But Kennan took little pride in his achievement, and bitterly denounced the use of containment to justify the Vietnam war. “Even after the Cold War had ended and the Soviet Union was itself history,” Gaddis writes, “Kennan regarded the ‘success’ of his strategy as a failure because it had taken so long to produce results, because the cost had been so high, and because the US and its Western European allies had demanded, in the end, ‘unconditional surrender.’ That outcome had been ‘one of the great disappointments of my life.’”

Kennan’s favourite quotation was John Quincy Adams’s 1821 speech proclaiming that the United States “goes not abroad in search of monsters to destroy.” It captured Kennan’s fear that in abandoning isolationism after the second world war, the United States would change from a nation that attempted too little internationally to one that tried to do too much.

In his first book, American Diplomacy, published in 1951, Kennan argued that American diplomacy was too often prey to “legalism-moralism” – Woodrow Wilson’s fourteen-point war aims speech of 1918, for example, or Franklin Roosevelt’s demand in 1943 that Germany and Japan unconditionally surrender. Delivered with the flair and passion of Kennan’s best writing, it was a strong warning against relying on principles while neglecting power. The book sold better than anything else he wrote and, characteristically, the moment it hit the mark he started to worry that people had misinterpreted his message.

Kennan was stung by the accusation that, like other foreign affairs realists, he was an amoral cynic whose obsession with power ignored law and morality. As Gaddis recounts, he told the historian Arnold Toynbee that he did not mean that Americans could abandon “decency and dignity and generosity”:

His point, rather, had been that the US should refrain from claiming to know what was right or wrong in the behaviour of other societies. Its policy should be one of avoiding “great orgies of violence that acquire their own momentum and get out of hand.” It should employ its armies, if they were to be used at all, in what Gibbon called “temperate and indecisive contests,” remembering that civilisations could not stand “too much jolting and abuse.”

Kennan argued that the United States must fight against North Korea, and win, to restore the pre-conflict division of Korea because of the systemic risk if China and the Soviet Union won the conflict. On Vietnam, however, by 1963 Kennan was urging the United States to get out quickly; it was in its interest to be free to exploit Sino–Soviet differences rather than fighting a major war in Asia.

In 1966, appearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, he offered American television viewers a five-hour tutorial on the perils in Vietnam. The NBC network broadcast Kennan’s testimony in full, confirming “his longstanding belief that style was as important as substance.” Kennan told the senators that America would lose far more prestige staying in Vietnam than it would by a swift pullout: “There is more respect to be won in the opinion of this world by a resolute and courageous liquidation of unsound positions than by the most stubborn pursuit of extravagant or unpromising objectives.”

Consistent with that line, Kennan condemned George W. Bush’s plans to attack Iraq. Just two years short of his hundredth birthday, Kennan could still summon eloquence and the lessons of history to denounce Bush’s evident determination to invade Iraq. “War has a momentum of its own and it carries you away from all thoughtful intentions when you get into it,” he told an interviewer in 2002. “Today, if we went into Iraq, like the president would like us to do, you know where you begin. You never know where you are going to end.”

That sadly prescient quote doesn’t make it into the book, which devotes only a few lines to his opposition to the Iraq war and his distaste for the Bush administration. This is one of the points of major difference between subject and author, because Gaddis has often written elsewhere in support of what he has defined as the Bush doctrine (“ending tyranny in our world”).

But give Gaddis the benefit of the doubt on his skimpy treatment of Iraq, which arrives near the end of 700 tightly wrought pages, often as polished in their prose as Kennan could ever have wished. Gaddis elegantly charts a life of complex thought that produced a written record running to millions of words. For a biographer, a bounteous archive can be both a blessing and a burden.

NOT least of the thoughts Kennan offered was his complete rejection of a hardline realist position – the ends justify the means – of which former US vice-president Dick Cheney is an exponent. At several points in his biography, Gaddis returns to Kennan’s argument that the limitations of our knowledge mean precise ends are difficult to define, much less achieve. If we can’t really know too much about what will be achieved, then methods are as important as objectives: strategy becomes “outstandingly a question of form and style” because “few of us can see very far into the future.” And bad means deliver lousy ends.

Coming from a man who had some record as a seer, that is an injunction to caution. Kennan said he learned as a policy planner that how one did things was as important as what one did. As for bureaucrats and diplomats, so for nations: “Where purpose is dim and questionable, form comes into its own.” Good manners, which might seem “an inferior means of salvation, may be the only means of salvation we have at all.”

What to say about a great strategist who concludes that simple politeness may save us all? Such are the many puzzles of Kennan, a natural pessimist who produced what was, at heart, a profoundly optimistic vision: if the West was strong and patient and true to its own values, then eventually the Soviet Union would defeat itself. And best of all, he was right.

In considering the US–China contest that lies before us, we can take heart from Kennan’s insight that harsh regimes cultivate the faultlines of their own internal failures. No matter how powerful an authoritarian regime may be, its future has roots in the past fears and failures of the nation it rules.

Kennan argued, correctly, that the commissars in the Soviet Union, like the tsars they replaced, would always prefer to turn away from major conflict with external forces because their greatest concern (and fear) was maintaining control over their internal empire. A similar insight can help throw light on the true power of today’s rulers in Beijing.

Kennan saw containment as a work in constant progress, requiring huge effort. Equally, though, war was never inevitable; if it came it was as much a product of misjudgement and blunder as of the force of history. That is a thought to hold onto in thinking about China; and also as some argue that George W. Bush’s war against weapons of mass destruction was right after all, it was just that one letter in the name of its target was wrong – it should have been Iran, not Iraq.

George F. Kennan: An American Life is a valuable book for anyone who must venture into the bowels of bureaucracy or seek the uplands of analysis and prescription. The grinding business of government and the effort to think and write clearly are parts of the same mountain. To follow Kennan’s ascent is to experience a significant contribution to the making of today’s international system. It is a biography set in the twentieth century that has much to offer in navigating the tough terrain of the new century. •