The Trump administration often touts tariffs as a way of exchanging short-term pain for long-term gain. Yes, there will be disruption in the short term, they argue, but once manufacturing returns to American shores and trade deficits disappear, prosperity will be supercharged.

That was always incredibly unlikely to be true. If it were, we’d probably see stockmarkets up since Trump’s election instead of down, since stockmarkets are forward-looking. As I explained recently, broad-based tariffs are simply incredibly unlikely to reindustrialise America, now or ever.

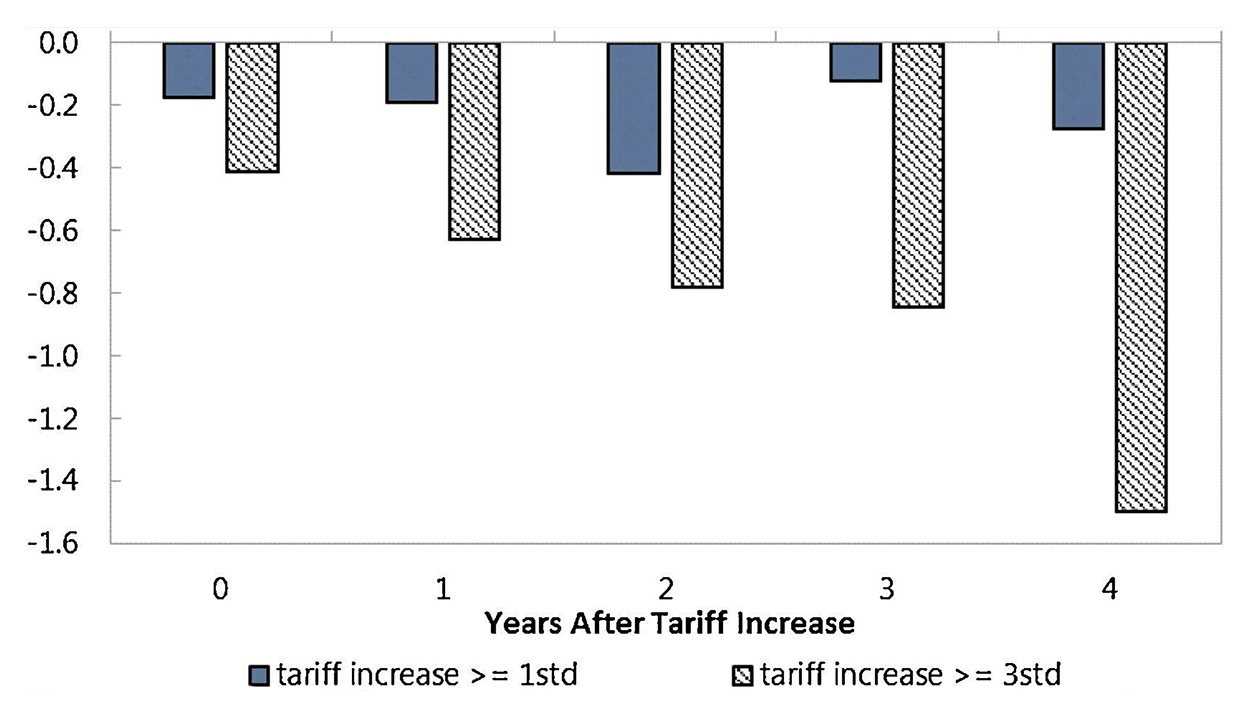

Evidence shows how this tends to be the case. You can just look at cases where countries raise tariffs by a substantial amount, and see what happens to their economies. This is what economist Davide Furceri and his colleagues did in 2020, and they found that GDP tends to go down after a big tariff hike. And for very large tariff increases, the magnitude of the output decline increases as the years go by — the long-term pain is worse than the short-term pain.

Output growth (annual) after tariff hike (per cent), according to first and third standard deviations. Source: “Are Tariffs Bad for Growth? Yes, Say Five Decades of Data from 150 Countries,” Journal of Policy Modeling, April 2020

Plenty of other research finds similar results, of course. And when you remove poor countries from the sample, the effect is even more stark; tariffs seem to lead to worse outcomes for rich nations than poor ones.

Of course, the causality could be reversed here; countries that are in economic trouble might tend to be the ones that resort to tariffs, and the tariffs might simply not be enough to save the countries’ economies. In macroeconomics it’s very hard to isolate cause and effect. But the facts seem consistent with the standard story, in which both (a) a loss of specialisation in production, and (b) deindustrialisation from the soaring cost of intermediate goods leads to long-term pain. On top of that, erratic tariff policies like Trump’s probably cause uncertainty that hurts business investment.

The part about deindustrialisation is especially important, because it undercuts the core beliefs of Trump and the MAGA movement. As the economists David Baqaee and Hannes Malmberg (2025) show, any simple model in which capital goods get taxed at higher rates is going to show less capital accumulation over time — in other words, deindustrialisation.

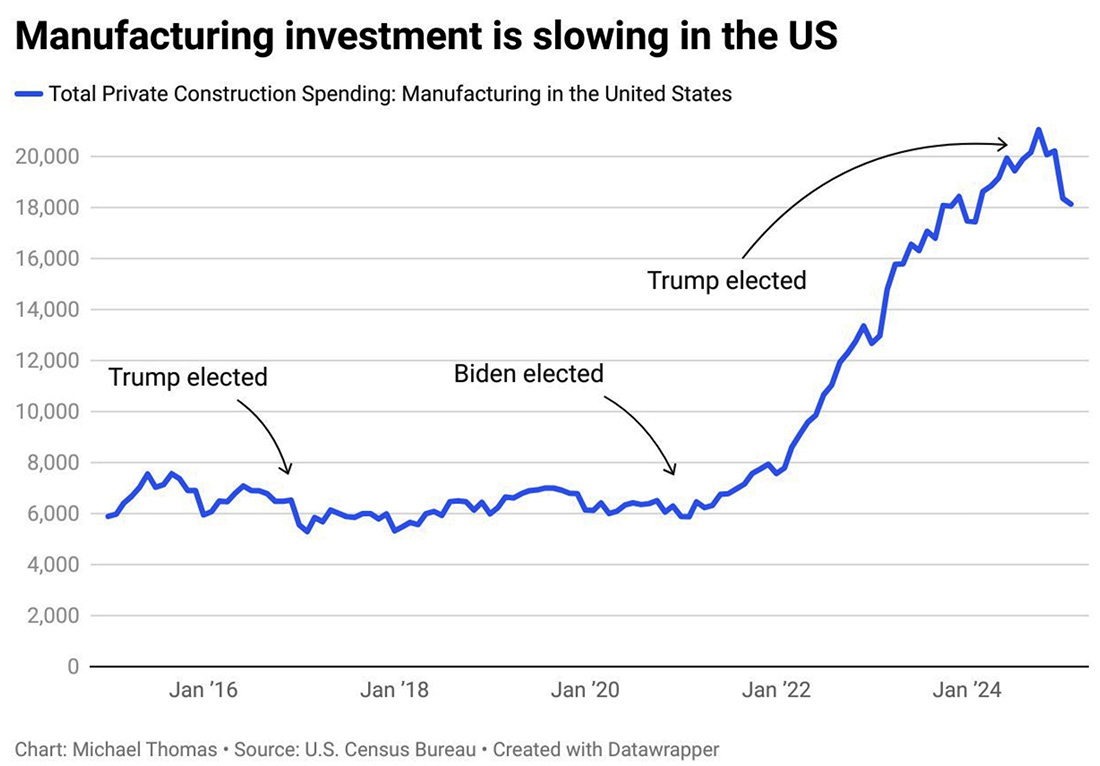

If this were counteracted by industrial policy and export promotion, it might be fine. But Trump is cancelling Joe Biden’s industrial policies and shows no interest in promoting exports (which will be hurt by tariffs and by other countries’ retaliation). Already, we see factory construction slowing down under Trump:

Source: Michael Thomas

People who simply take it on faith that tariffs boost US domestic manufacturing, like Michigan’s Democratic governor Gretchen Whitmer, need to realise that the opposite is often true, especially when the tariffs fall on capital goods and intermediate goods. This is not a policy that will revive Michigan, or the Rust Belt, or the blue-collar workforce, or the forgotten man of America. •