Think of an existentialist and you might picture a Frenchman in a trench coat, a severe German or a lugubrious Russian. Their writings expose the human condition in the cold light of grand abstractions: being-in-itself, authenticity, freedom and responsibility, the absurd, angst, meaninglessness. There is a musty mid-twentieth-century aura around these ideas, like bebop and monochrome photographs.

Mariana Alessandri’s new book Night Vision: Seeing Ourselves through Dark Moods presents a revived and colourised existentialism. Her philosophical authorities are gender balanced and come, with a few exceptions, from the New World. Alessandri hopes to convince her readers that the tragic vision of the existentialists still has value, and that their embrace of the darker sides of human experience is all the more urgent now.

A Latina philosophy professor and self-described Eeyore, Alessandri tells the reader she feels “pelted by positivity.” She sees a deeply problematic emphasis in American culture on being happy and optimistic at all costs. Her concern is widely shared, as many takedowns of “toxic positivity” attest, Barbara Ehrenreich’s Smile or Die, published in 2009, being the most well known.

Ehrenreich urged her fellow citizens “to recover from the mass delusion that is positive thinking,” a delusion “that encourages us to deny reality, submit cheerfully to misfortune, and blame only ourselves for our fate.” This obligatory uplift turns people inward when they should be changing the world. It removes the safety net of compassionate support when people falter because it makes happiness and success a purely personal responsibility.

Alessandri shares this dim view of a culture that obliges us to be shiny, happy people — a culture that tells those who are miserable to stop moaning, turn their frowns upside down, and try harder to lift themselves up by their hedonic bootstraps. Self-help writers lead the way by promoting the idea that we should strive for happiness above all else and illuminating the true path to self-improvement.

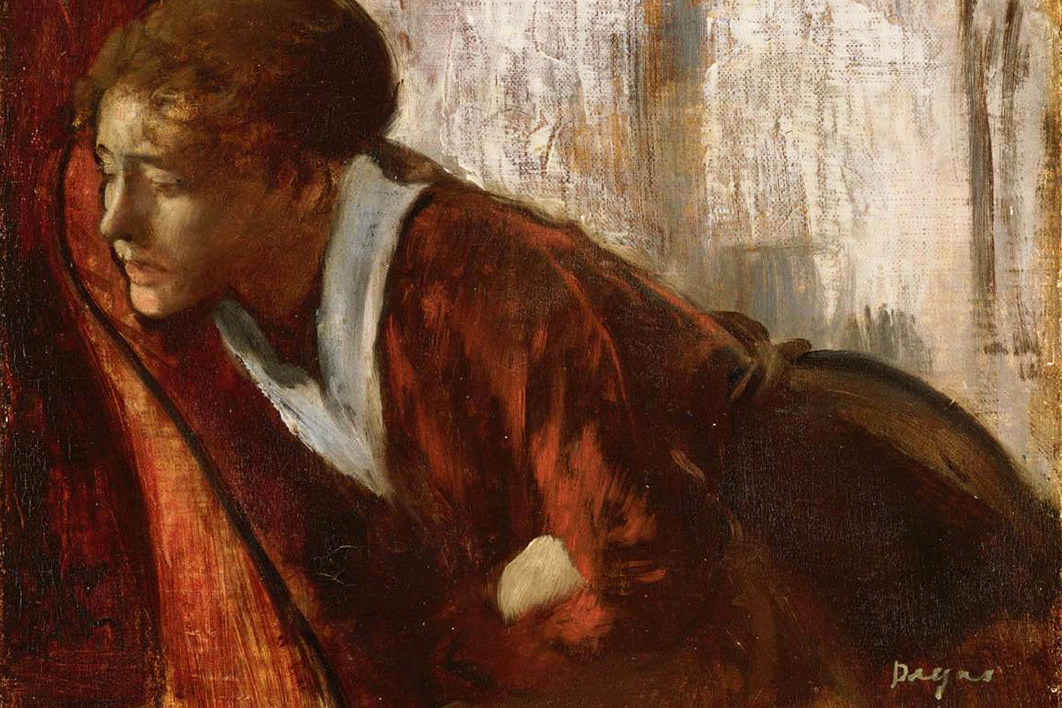

For too long, Alessandri writes, we have associated light with goodness and disparaged and dreaded the dark, including dark moods and dark skins. We should therefore embrace “the truth of darkness” and “turn down the lights and stop smiling.” The central chapters of Dark Vision each take a form of emotional darkness and explore it with existential company.

Sadness and depression, for example, are not negative states to be avoided, stoically endured or reasoned away but elements of what Spanish philosopher Miguel de Unamuno referred to as the tragic sense of life. Mental pain humanises us and enables compassion and deep connection. Alessandri cites feminist scholar Gloria Anzaldúa’s theoretical and autobiographical writings as rejecting the idea that depression is weakness, brokenness or disease, and offering a pathway to self-knowledge by “seeing depression by the light of the moon.”

Grief receives similar treatment. By Alessandri’s account, our obsession with brightness leads us to expect the bereaved to take action to overcome their loss and to be intolerant when they seem to succumb to it. Grief is often misrepresented as irrational and shameful, especially if it endures. Taking the novelist C.S. Lewis’s stance, detailed in his powerful A Grief Observed, we should “grieve hard” rather than privately stifle the pain of loss.

Kierkegaard is the existentialist guide through anxiety and dread, as he was for the protagonist of David Lodge’s comic novel Therapy. Alessandri criticises mainstream psychiatry for seeing anxiety as evidence of a chemical imbalance or a broken brain, and mainstream psychotherapy for piling shame on top of it by blaming patients who fail to recover. Both critiques attack straw men, but they set up a sharp contrast to a Kierkegaardian view of anxiety as “the dizziness of freedom” and a way of being “excruciatingly alive to the world.”

Anger, perhaps an odd choice for a study of dark moods given its fiery connotations and the undeniable pleasure to be found in righteous indignation, receives its own existential reframing. African-American writer Audre Lorde teaches that anger, unlike hate, enables social progress, and Argentine philosopher Maria Lugones instructs that it preserves our dignity in the face of injustice and grounds us in the reality that something is wrong with our situations, not our selves.

Both thinkers counsel that we should listen to and learn from anger rather than repress it, a conclusion hard to deny. The awkward reality that people tend to see their own anger as morally justified and others’ anger as irrational hatred is overlooked, as is the dissonance between anger’s progressive credentials and its role in fuelling violence.

Night Vision is a useful counterweight to some contemporary styles of thinking that equate mental health with happiness, but it has its own weaknesses. Often the radicalism of its claims is overstated by distorting those it opposes. The book caricatures orthodox approaches to mental ill health as if they amounted to nothing but disease-mongering and patient-blaming. Occasionally it veers into misrepresentation, as when Alessandri claims that psychiatry now defines grief lasting more than two weeks as mental illness and sees any amount of anxiety as dysfunctional.

The idea that mental health workers, avid consumers of popular psychology or everyday folk would find it a revelation to be asked “what if truth, beauty and goodness reside not only in light but also in darkness?” is absurd. The contemporary mental health landscape is arguably as open to emotional darkness as it ever has been. Lived experience is amplified; destigmatisation has progressed to the point where few people think depression reflects weak character, laziness or neurotic wallowing; sympathy and support for people disclosing mental health problems is high and rising; and people enthusiastically and sometimes promiscuously embrace diagnoses that would once have been shameful secrets.

Some writers now worry that the pendulum has swung too far towards valorising mental ill health and raise concerns about the spread of illness-based identities. It is hard to square this view with Alessandri’s analysis of a “nyctophobic” society populated by tough-minded stoics. It is one thing to avoid toxic positivity and seek meaning in suffering, quite another to tell those who suffer that their depression reveals their superior sensitivity and depth of feeling, that their anxiety “is a sign of emotional intelligence,” that attempts to motivate them to recover constitute shaming, or that their troubles stem only from a broken society.

These prescriptions point to one of the ironies of Night Vision. It overtly rejects the self-help genre while co-opting its conventions. Highlighting the author’s relatability through folksy self-disclosure and popular culture references (The Real Housewives of New Jersey, Entenmann’s donuts), repetitively invoking a few Big Capitalised Ideas (Light Metaphor, The Brokenness Story), and cosying up to a few admired self-help writers who supposedly resist the dominant approach while somehow managing to be among its biggest stars (Brené Brown, Susan David), are moves from the self-help author’s playbook.

Some of Alessandri’s meme-able sayings fall a little flat — “diagnosis doesn’t rhyme with dignity” (but neither does “darkness”) — but their mere existence points to her proximity to the self-help genre. This effort to appropriate a successful rhetorical style does at least have the advantage of softening some of the prescriptions a less compromising approach to existential insight might make. Alessandri defends the value of misery and attacks psychiatric reductionism, but she doesn’t want you to stop taking your antidepressants when you start reading Kierkegaard.

As therapy-speak becomes increasingly popular, Night Vision could be seen as offering another dialect with more intellectually elevated influences. That may not be such a bad thing. Philosophical ideas about emotion and suffering offer a perspective on mental health and illness that can complement, challenge and complicate the familiar chatter about diagnostic labels and wellbeing.

Alessandri makes a good case that existentialist writers should have a seat at the table when mental health is discussed rather than continuing to sit at another, smaller table feeling superior and overlooked, as theorists tend to do. If sometimes she engages in caricature and turns her own insights into self-help nostrums, that will at least reach a larger audience than philosophy texts from university presses ordinarily manage. Night Vision is a stimulating and sometimes maddening contribution to broadening the scope of mental health discourse. More please! •

Night Vision: Seeing Ourselves through Dark Moods

By Mariana Alessandri | Princeton University Press | $37.99 | 216 pages