My first encounter with Malcolm Bligh Turnbull did not end happily, though it gave something of an insight into the man who, three decades later, would become Australia’s twenty-ninth prime minister.

It was 1986 and I was working in Canberra as foreign affairs and defence correspondent for the Age. Turnbull, who had dabbled briefly in journalism before realising there was a bigger future and a lot more money in media law, was a cocky young lawyer about to secure an outsized international profile. The publicity would launch him towards his lifelong ambition of becoming prime minister.

On the morning in early November I picked up my home phone to find Turnbull on the line. I had landed a minor scoop that had appeared on the front page of the Age. On the basis of a cabinet leak, I reported that the Hawke government had resolved to join a case in the NSW Supreme Court in support of the British government’s bid to block publication of Spycatcher.

Former MI5 agent Peter Wright, then living in retirement in Tasmania, had spent much of his twenty-five-year career with the British spy agency hunting Russian moles — a busy enterprise during the era in which top agents Kim Philby, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean were revealed as traitors. Wright had investigated Roger Hollis, head of MI5 from 1956 to 1965, and his book set out his case that Hollis was another double agent and should not have been cleared. The Thatcher government had obtained a preliminary injunction to stop the book’s publication in Britain and now wanted to stop its release in Australia.

The revelation that Hawke’s Labor government was getting into bed with Britain’s Tories to silence a whistleblower was significant news, although ultimately its support would have little impact on the outcome of the case.

The morning phone conversation began cordially enough, with Turnbull complimenting me on a “great story” before requesting that I tell him who my source was. When I gently pointed out that, as a former journalist, he should understand that revealing sources was the equivalent of breaching the seal of the confessional, the caller exploded, describing me in terms that might make even sophisticated Inside Story readers blush. Before slamming down the phone, he declared, “Don’t ever expect anything from me.”

It had never occurred to me that I might expect anything from Malcolm Turnbull, and in the years since he left with a dial tone I was relieved never to find myself in a situation of needing anything from him — beyond, perhaps, the republic he was supposed to deliver and some serious action by his faction-riven government on global warming.

A few days after the morning call, I was seated in courtroom 8B of the Supreme Court in Sydney for the commencement of the Spycatcher hearing. While I’ve forgotten most of what happened over subsequent days, two indelible memories remain.

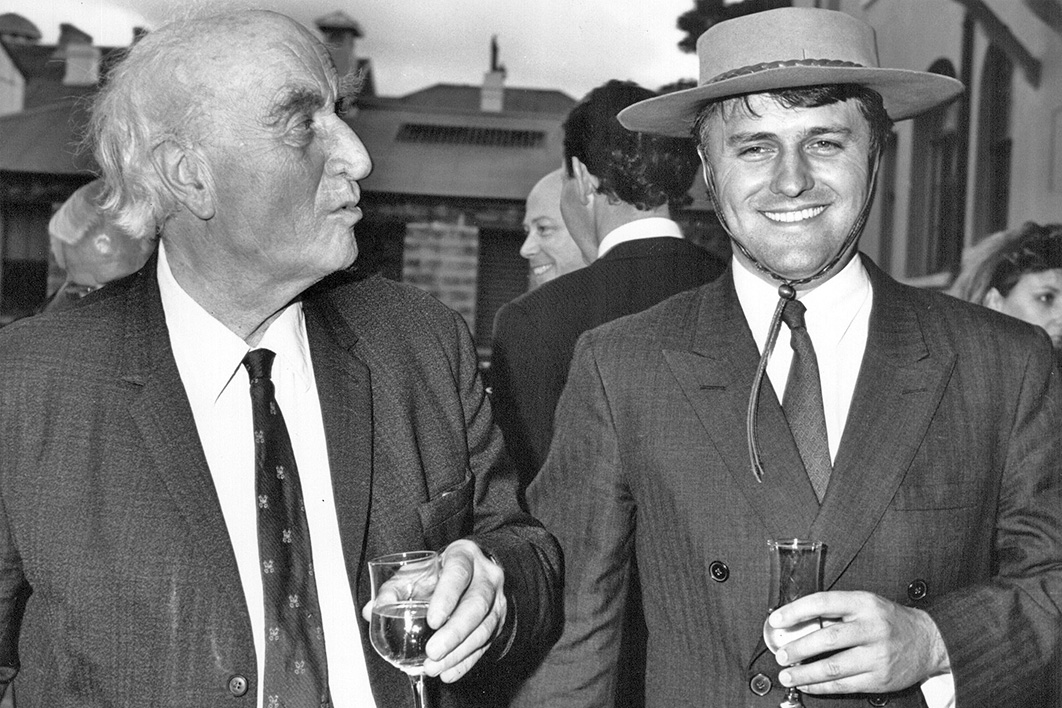

The first was the brash and theatrical style with which the thirty-two-year-old Turnbull conducted himself, and how much his antics were indulged by Justice Philip Powell, who seemed almost in awe of the young Rumpole. The other was the starkly contrasting presence of the urbane Sir Robert Armstrong, cabinet secretary and head of the British civil service, who had been sent by Thatcher as her government’s principal witness.

In an immortal moment, Turnbull was questioning Armstrong about Andrew Boyle’s 1979 book The Climate of Treason, which effectively outed Anthony Blunt as the fourth member of the Cambridge ring of Russian spies. Turnbull was seeking to demonstrate that the British authorities had turned a blind eye to the disclosure of official secrets in Boyle’s book and shouldn’t be treating Spycatcher differently.

Turnbull had established that the British government was well aware of the Boyle book before its publication and had, indeed, obtained a copy, yet Armstrong had written to the publisher asking whether Thatcher could be provided a copy to enable her to be fully informed should she need to make a public statement. Turnbull pressed Armstrong as to whether the letter was calculated to mislead. Armstrong conceded the point but insisted that creating a misleading impression did not amount to lying.

Turnbull: What is the difference between a misleading impression and a lie?

Armstrong: A lie is a straight untruth.

Turnbull: What is a misleading impression — a sort of bent untruth?

Armstrong: As one person said, it is perhaps being economical with the truth.

The delicious phrase might have danced straight out of a script for Yes Minister, the classic TV series at the height of its popularity at the time. And while it may have originated with Edmund Burke’s expression of “an economy of truth,” it was propelled into the lexicon of global political commentary by Sir Robert Armstrong in an austere Sydney courtroom in November 1986.

These memories have been stirred with the arrival of Malcolm Turnbull’s memoir A Bigger Picture. And big it certainly is — a 700-page, densely typeset tome landing, fortuitously for its author, in the time of national home detention when surely no one has anything better to do than relive the career of our most recently superannuated statesman. (And should any reader bridle at the size of the task, be thankful the author only lodged at The Lodge for just under three years.)

Turnbull had already gained prominence working in the early 1980s as general counsel for media mogul Kerry Packer and successfully running his defence against scurrilous allegations raised in the Costigan royal commission into union corruption and tax evasion. But the Spycatcher trial would take his brand to another level.

As Turnbull writes, he was approached to run the case by a London solicitor representing the book’s publisher, Heinemann. The pitch was hardly enticing for an ambitious lawyer who had only started in private practice a few months earlier. He was advised that Heinemann was depressed about the British injunction, was ready to throw in the towel and would only proceed if it could be done cheaply.

In the end, Turnbull agreed to do it for a flat fee of $20,000. It would turn out to be the best low-budget commission of his fabulously well-remunerated career as a commercial lawyer and, later, merchant banker.

Thanks largely to the admissions he extracted from the hapless Sir Robert, Turnbull won the case. Justice Powell ruled that having failed to take action to prevent the publication of Their Trade Is Treachery and other books with similar content to Spycatcher’s, the British government had “surrendered any claim to the confidentiality of that information.” When the case went to the NSW Court of Appeal later in 1987, Turnbull won again.

Obstinate to the end, the British then took the case to the High Court, where in early 1988 their repudiation was complete — the judges voted seven–nil in favour of Spycatcher. The road to greater fame and fortune now unfolding before him, Malcolm Turnbull found no need to be economical with the truth.

“I’d taken on the UK government and its army of top lawyers, fought the case through a trial and two appeals and won,” he writes. “What appalled many of my former colleagues at the Bar was that not only was I absurdly young, at thirty-two, but that I hadn’t appeared as a barrister, but unrobed as a solicitor. Surreally, the case was much bigger news in London than in Australia. I was being encouraged to capitalise on my international notoriety — move to the Bar in London or New York; head spinning really.” •