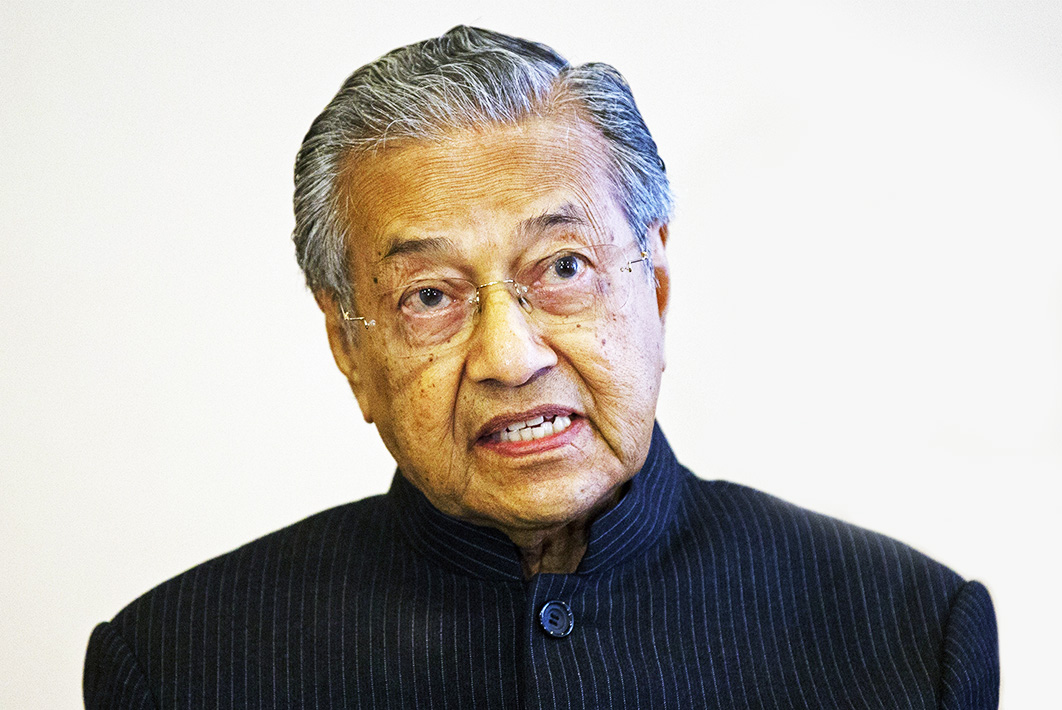

“Throughout my premiership, I led five election campaigns,” Mahathir Mohamad reminded me when we talked in his office in Putrajaya last year. Now he’s leading another election campaign, but not for his former party, the United Malays National Organisation, or UMNO, or for the coalition it leads, the Barisan Nasional.

This time, Mahathir is chairing Pakatan Harapan, or Alliance of Hope, a new grouping of opposition parties that aims to oust prime minister Najib Razak, the current UMNO leader, at the next Malaysian election, due before the end of August 2018. It was Mahathir who elevated Najib into his position in 2009 — “I thought Mr Clean would be a good prime minister,” he told me — having briefly left UMNO to pressure his own successor, Abdullah Badawi, to resign.

Mahathir has resigned from UMNO before, but never to mount a project like this one. Famously confrontational, he is Malaysia’s longest-serving prime minister, in office from 1981 to 2003, during which time he attracted heavy criticism for restricting civil liberties using Malaysia’s Internal Security Act. Many of the activists he targeted in those days — people like Lim Kit Siang from the Democratic Action Party — are now alongside him in Pakatan Harapan.

Mahathir is working through his new party, the Parti Pribumi Bersatu Malaysia, or the United Malaysian Indigenous Party (the word “indigenous” being a contested term in Malaysia). If he succeeds in removing Najib, he says, he will aim to limit the damage Malaysian prime ministers can inflict. Last week, at a discussion of future directions in Malay Muslim politics organised by Parti Amanah Negara, another Pakatan ally, he announced that the opposition would seek to limit future prime ministers to two consecutive terms.

Even so, Mahathir continues to alienate long-time democracy activists like Kua Kia Soong, adviser to civil rights organisation Suaram. But the former PM’s supporters in Pakatan will have calculated that his critics will trade off those reservations against the chance of ousting Najib. Mahathir’s statements are nevertheless crafted to neutralise these activists’ criticisms as much as possible, and to calm the nerves of voters who sense that, even at ninety-two, Mahathir is still powerful enough to capture Pakatan Harapan.

Mahathir is in an awkward position for another reason. He can only afford to partially distance himself from a legacy he otherwise views with pride. Today’s Malaysian adults — including those who distrust Mahathir — witnessed their nation grow rich during the long economic boom he led with his deputy and finance minister, Anwar Ibrahim. When the two men disagreed about how to deal with the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, Mahathir sacked Anwar and introduced stimulus measures and currency controls.

Internal UMNO opposition to Mahathir coalesced around Anwar. Mahathir responded with the corruption and sodomy charges that led to his former deputy’s imprisonment between 1999 and 2004. Pakatan Harapan is the latest in a series of opposition alliances that formed against Mahathir in subsequent years. In 2013, Anwar led a previous iteration, Pakatan Rakyat, to a dramatic win in the popular vote (though not in numbers of seats). Fuelled by a historically high voter turnout and a backlash in Malaysia’s cities, that near-loss stripped the Barisan Nasional of much of its legitimacy.

Now Anwar is in prison again after a second round of sodomy charges. Although he can’t lead Pakatan into the next election, he is still present in its leadership line-up, resuming the old alliance between himself and Mahathir.

Najib himself is under investigation by the US justice department in the largest kleptocracy case it has ever undertaken. The case revolves around the Malaysian state development fund, 1Malaysia Development Berhad, or 1MDB, which transferred around US$1 billion (A$1.25 billion) into Najib’s personal bank accounts before the scandal broke in 2015. At the time, many commentators declared that Najib’s end was near, but they continue to wait for their prediction to come true.

Najib can still win Malaysia’s next election, even though the US justice department and the FBI have found that his stepson Riza Aziz and associate Jho Low used 1MDB funds to finance a lavish, jetsetting lifestyle. The justice department has seized assets purchased by these two men, including jewels, film rights and luxurious real estate holdings, and is holding them in trust.

The prime minister has built a cache of bureaucratic weapons to help keep himself in power, including new national security laws that give Malaysia’s security agencies unprecedented powers to search and arrest, declare special security zones, seize property, impose curfews and detain without trial. Staying in power might well help Najib avoid indictment in the United States, as “Malaysian Official #1” — a moniker assigned to him by the justice department. Riza and Low may not be so lucky: last week, former US ambassador to Malaysia John Malott warned of their imminent criminal indictment. In an open letter published on a Facebook page run by Malaysian cartoonist and government critic Zunar, Malott called Najib an international pariah.

Najib is working hard to deflect these criticisms onto Mahathir. Last week, he sought to draw back international investors who fled Malaysia after the 1MDB scandal broke. (Between 2014 and 2016, with the 1MDB scandal pointing to the entrenched corruption in Malaysia, capital outflows from the country’s equity market totalled nearly RM20 billion, or A$5.8 billion.) Speaking at the Malaysian stock exchange’s Invest Malaysia 2017 forum, Najib admitted that there had been “lapses in governance” at 1MDB, but argued that his response had been superior to Mahathir’s conduct during his own twenty-two-year rule. To add weight to this point, he announced that he would establish an Integrity and Governance Unit in all government-linked business entities, which together dominate the Malaysian economy.

Meanwhile, 1MDB has been bailed out by Chinese firms. The Malaysian ringgit has begun to recover from the scandal’s impact and the World Bank is forecasting a lift in national GDP. Najib recently delivered a new light-rail line for Kuala Lumpur and Klang Valley commuters, and has announced high-speed intercity rail projects funded by Chinese investments.

Najib is, however, patently shaken by Mahathir’s entry into opposition politics. He used the Invest Malaysia forum to urge international investors to avoid the opposition, which he described as resembling a “return-to-work program for old age political pensioners.” The number one pensioner, of course, is Mahathir, under whose leadership, Najib argued, “the Malaysian people had to pay a very high price so that a few of his friends benefited.”

For Najib, one big danger lies in Mahathir’s vast web of contacts. Even more than the rest of the opposition leadership, the former PM has high-level access in international political and business circles. Collectively, the opposition leadership has internationalised the 1MDB scandal by arguing to Malaysia’s friends and allies that they would be better off without Najib. Mahathir has been doing his share, courting the international media, travelling extensively, and granting interviews to academic researchers he would never have agreed to meet as prime minister.

As for his reception at home, he is broadly admired, whether his activist critics can stomach his popularity or not. Last weekend’s social media chatter, for example, focused on an online opinion poll conducted by liberal-leaning online media outlet Malaysiakini. The problems of selection bias and multiple voting are pronounced in polls like this one, yet Mahathir’s critics and opponents will notice the numbers: 75 per cent of those reading in Malay, and 69 per cent of those reading in English indicated that they “trust” him.

Yet Najib’s attacks on Mahathir are not limited to the corruption theme; he is also ramping up the racial and religious rhetoric. He has ferociously attacked Mahathir’s present collaboration, via Pakatan Harapan, with Malaysia’s Democratic Action Party. Najib is pointing to the DAP’s overwhelmingly ethnic Chinese membership as proof that Pakatan is a front for a Chinese takeover of Malaysia.

In contrast, Najib’s communications and multimedia minister Salleh Said Keruak asserted last week that only a government led by UMNO can protect the rights of Malaysia’s Malay Muslims — including guaranteeing the constitutional provisions that enshrine Malaysia’s monarchies and entrench Islam as the nation’s official religion. Most importantly, Salleh claimed, only UMNO can defend the “special rights” of Malay Muslims, including their access to a range of social assistance provisions.

But some of these special rights are emerging as weak points for Najib, and another scandal is affecting precisely the constituency he needs most — rural Malay Muslim voters who hold disproportionate electoral power thanks to a system marked by gerrymandering and malapportionment. This scandal is centred on FELDA, the Federal Land Development Authority, which was founded in the 1950s to address rural poverty and landlessness using market mechanisms.

Since independence in 1957, FELDA has funded the resettlement of selected rural families in smallholder plots, where they produce rubber, oil palm and other cash crops. Like so many other Malaysian government agencies, FELDA also manages corporate entities, including FELDA Global Ventures. Today, FELDA is performing poorly, with low yields and depressed commodity prices leaving many of its settlers in serious debt. They are obliged to repay to FELDA regardless, while shares in FELDA Global Ventures, which many settlers have purchased with more loans, are declining in value.

The problems don’t end there. Malaysia’s anti-corruption commission found that another FELDA company, FELDA Investment Corporation, purchased a London hotel at an inflated price. Last week, the commission raided the office of consultancy firm Deloitte Malaysia in connection with this purchase. Meanwhile, FELDA Global Ventures chair, Isa Samad, was moved on earlier this year over questionable deals of his own. Last year, Mahathir told me that “most of the electorate” might not be “able to understand what 1MDB is about,” but FELDA is a scandal they certainly can.

Importantly for both sides of politics, FELDA settlers dominate fifty-four electorates that Najib’s Barisan Nasional relies on to form government. Opposition parties have seized on the FELDA revelations, arguing that UMNO’s own corruption is precisely what is undermining settlers’ special rights. According to media reports, several people are likely to be charged over FELDA’s financial dealings in the near future.

Last week, Najib announced that nearly 100,000 FELDA settlers will soon each receive RM5000 in relief payments, an amount settlers have already denounced as insufficient to resolve their debt problems. Meanwhile, FELDA pressure groups are openly bargaining with Najib, telling him that if settlers are not delivered further assistance, then the opposition might make “inroads” in FELDA-dominated electorates.

Mahathir’s aim is to cut through Najib’s racial and religious rhetoric to convert rural voters’ own mini-1MDB scandal into votes for the opposition. Assuming he achieves this, he will be in a stronger position to persuade Malaysia’s royal, bureaucratic and military elites that they should accept the result and decline to support Najib if he tries to use his new national security laws. Should Najib use his emergency powers to avoid an election altogether, Mahathir’s role will be to emphasise Najib’s weakness.

This is why Najib’s racial and religious attacks on Mahathir are so important — they are designed to prevent this Malay Muslim constituency from even thinking of voting for Mahathir. For his part, Mahathir will aim to show that he has an answer to his charges.

Since the 2013 election, Najib has been courting Islamist party PAS with suggestions that he might agree to introduce draconian hudud penalties for Malay Muslims. The representation of his allied Chinese and Indian parties in the Barisan Nasional, meanwhile, has almost been wiped out by non-Muslim voters’ flight to the opposition.

Mahathir, on the other hand, is now running a multiracial coalition that nevertheless purports to protect Malay Muslim rights — which sounds very much like the Barisan Nasional in the days when Mahathir and Anwar were running it. Their alliance was also characterised by a strong Islamisation of public life that nevertheless gave no quarter to PAS’s desire for hudud. Many Malaysians’ nostalgia for that period has grown only more palpable since Najib and PAS began to publicly float the idea collaborating more closely to further Islamise Malaysia’s legal system.

The opposition is also subtly signalling an economic transition that will free FELDA settlers and other rural Malaysians from the unsustainable lifestyles that lock them into voting for Najib and the Barisan. Its youth wing is promising to create a million new jobs, build more affordable housing, raise the minimum wage and get rid of foreign workers — a formula designed to signal its willingness to end Barisan’s symbiotic relationship with rural dependency once and for all.

As Mahathir told me last year, “I have always said that in this country there must be a kongsi — a sharing — between the Malays, the Chinese and the Indians. That is the only way.” If there’s one thing Malaysians of all ethnic and religious backgrounds can build a kongsi around, it’s their distaste for foreign workers, many of whom come from Bangladesh, Burma, Indonesia and Nepal.

Mahathir’s formula is not guaranteed to work. But reports indicate that thousands of people, most of them aged thirty-five or younger, are turning up at his new party’s meetings. Despite his age, he seems not to have lost his capacity to speak to Malaysians, no matter how much frustration this might cause his critics. ●