A trailer for ABC’s The Beautiful Lie promises an “outstanding new drama” based on Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina. We see close-ups of an erotic kiss, an arty-looking man and a beautiful socialite exchanging looks of deep intensity, a row exploding at a dinner party and a man crawling across the table in a fit of rage. Umm. Tolstoy? Why do they think this has anything to do with Tolstoy?

There are no rules, of course, about plundering the classics for contemporary remakes, however loosely the original ingredients are interpreted. The only relevant criterion is whether the remake succeeds in its own terms. West Side Story lifts the dramatic architecture of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet and places it in another world and time. Subplots, themes, the poetic genius of the original lines: all are gone, and what matters is that the creators of the new work are true to their own forms of genius.

But if you are going to claim any serious creative relationship with a work of genius, you may need some genius to bring to it, otherwise you risk looking as if you have tickets on yourself. Or it looks as if you really have no respect for this baggy old classic, in which people keep interrupting their love lives by tilling the fields, going to war, taking marathon journeys across vast country, having long political arguments, and getting embroiled in existential crises.

Judging from the critical reception so far, The Beautiful Lie has plenty of admirers. Condemning an “acclaimed” ABC drama in the Australian media is never a popular move, but sometimes you have to tell it as you see it. What I saw in the first two episodes was a bunch of actors in overblown emotional registers, the camera constantly pushing into their faces to bring the viewer into unseemly intimacy with whatever they were purporting to feel. This is passion, right?

Such literal-minded striving for dramatic intensity is not what quality television drama is made of. Tell the camera to back off a metre or two. Tell the actors to rein it in. Don’t pick almost the entire cast for their cool and sexy looks, or encourage them to flaunt them constantly. Strong drama is elsewhere. Perhaps later episodes will find some, and the story will deepen if it really does feed off those well-thumbed copies of the novel displayed for the cameras in the rehearsal clips included as promotional extras on the iView menu.

The Beautiful Lie also has plenty of rivals at the moment, and comparisons don’t do it any favours. Homeland series 5 is showing on One and the second series of Fargo started last week on SBS, as did a repeat of the complex and gripping family drama Legacy (from the Danish company that made The Killing). And a replay of the very first episode of Sherlock on ABC was a welcome surprise on Thursday night. Sherlock is an unadvertised replacement for The Musketeers, which has been dropped from the prime 8.30 timeslot without explanation. The Musketeers isn’t bad, but Sherlock is seriously good, and its originality is most subtly evident in the first season.

Benedict Cumberbatch as Sherlock and Martin Freeman as Dr Watson, free of the cult status they were to acquire as the series took hold, stake out the parameters of the characters in a social world radically but not entirely different from that in which Arthur Conan Doyle originally planted them. In a shrewd touch of psychological updating, Sherlock has Asperger’s syndrome rather than a severe case of Victorian straitjacketing. This also makes sense of his extraordinary capacity to register technical and factual details. (A note to ABC drama producers: how much more interesting is it to watch a character who can’t or won’t show feeling than one who keeps letting you have her every emotional reaction full in the face? Somehow the mind in close-up is so much more convincing – and compelling – than the heart, which is never accessible to the camera in the way some TV directors insist it must be.)

Instead of the rather staid game of question and answer in which Conan Doyle’s Holmes showcases his genius to Watson, Cumberbatch’s Sherlock goes into verbal overdrive, thinking aloud in high-speed monologues. These are a tour de force for the actor, whose virtuosity with the lines is counterpointed by Martin Freeman’s deft way with body language. It’s Watson’s role to be the one who reacts to things, but he does so off the beat, always with his own kind of perverseness and unpredictability.

The art of the remake, though, also lies in a sense of what not to change. So much of Conan Doyle’s London is still there – its dark alleyways, the Baker Street terraces where Holmes kept his consulting rooms, the all-knowing cab drivers, the Whitehall rooms where Sherlock’s brother Mycroft lurks, keeping everyone under surveillance. London always was a leading character in the stories, and Sherlock keeps it that way.

Flatscreen technology has opened up the field of television cinematography. What was once the small screen now lends itself to expansive landscapes and multifaceted interiors that release the viewer from the once claustrophobic environment of the lounge room. The world of Fargo, though, is more likely to induce agoraphobia.

Small-town life in late 1970s Minnesota retains the surreal quality of the original Coen brothers film. Pockets of community huddle together, with individuals occasionally leaving their cluttered interiors to cross the vacant snowbound landscape that is their wider world. There’s a strong genre feel about those shots of cars on flat straight highways going about who-knows-what bad business. It’s almost as if the bad stuff is something they pick up in transit. It hitches a ride to the nearest place where it can invade the safety of the residents.

Cops and criminals seem to always be cruising out there, and an ordinary citizen who gets on the road at the wrong time can connect up with something ugly. In the first episode, Judge Wundt leaves the courthouse in Fargo and is followed out on the highway to the Waffle Bar on the outskirts of Luverne, where she stops for a bite. In the confrontation that follows, she overplays her hand and four people wind up dead, two immediately and two in a continuing chapter of accidents, as they stagger out on their last legs, wobbling absurdly across the snow. One is distracted by strange blue lights, airborne in the night sky, and fails to register the headlights of a vehicle hurtling towards him. Its driver, local beautician Peggy Blomquist (Kirsten Dunst), collects him clean through the windscreen and doesn’t know what to do next.

So what she does is one wrong thing after another, implicating her adoring husband Ed in the sinister chain of events. Ed, a local butcher, finds himself using his skills in a way he’d never have imagined, while the things he has imagined – having a family, owning the shop – vanish from the horizon.

Fargo doesn’t so much show the banality of evil as the perverse relationship between evil and the precious banality of ordinary lives. These are people who make simple demands on the world. They want to go on day after day hearing the shop bell ring and talking to the customers, ordering new products for the hair salon, cooking big plates of plain food and eating them at the kitchen table with a husband or wife and maybe a child or two for company.

This is a theme with plenty of mileage in it, especially when the scenes of everyday life are counterpointed by bizarre explosions of the macabre that will, as one character says, only get bigger. The counterpoint structure is itself generic. You could fairly say that there is nothing original about Fargo. The formula is equal parts Twin Peaks, Reservoir Dogs and the Coen brothers movie: all deal in the same blend of violence and farce, surrealism and soap. And they have the same trademark scenes – in the diner, at the kitchen table, the gas station and the local cop shop, and, of course, on the lonesome highway.

Sooner or later the formula will pall. It’s kept going here by finely tuned scriptwriting from Noah Hawley and by nuanced acting. Many of the reviews for Fargo seem to favour season 2 over season 1, but I’m not so sure we’re looking at a build in dramatic strength here. I miss the sharpness of psychological focus in season 1, with its byplay between Martin Freeman, as a panic-stricken local guy with a few sheep missing in the top paddock, and natural born killer Billy Bob Thornton, who negotiates his moves three steps ahead of everyone else. Kirsten Dunst heads the cast list for season 2; with her red beret and waves of blonde hair she looks like a throwback to Bonnie Parker, but the charisma is missing. So far, the script doesn’t give her enough to work with and the storyline lacks a centre of gravity. The tensions are diffused across too many characters, going (quite literally) in too many directions.

Quality TV is an increasingly competitive business, and staying at the forefront is a tough challenge. The breakpoint often comes in the third series, where there is either a well-conceived development that carries on into series four and onward, or a failure of nerve that signals the beginning of the end. Homeland passed the breakpoint with flying colours by ditching the increasingly tedious romance focus and killing off Brody (Damian Lewis), who was its original lead. Lewis is a fine actor, but he’d played too many traumatised soldiers and the repeated scenes of his perfectly toned torso getting a flogging in the torture den carried sadomasochistic overtones that got pretty wearing. The production team made a clever and unorthodox decision in promoting middle-aged CIA boss Saul Berenson (Mandy Patinkin) to the fore.

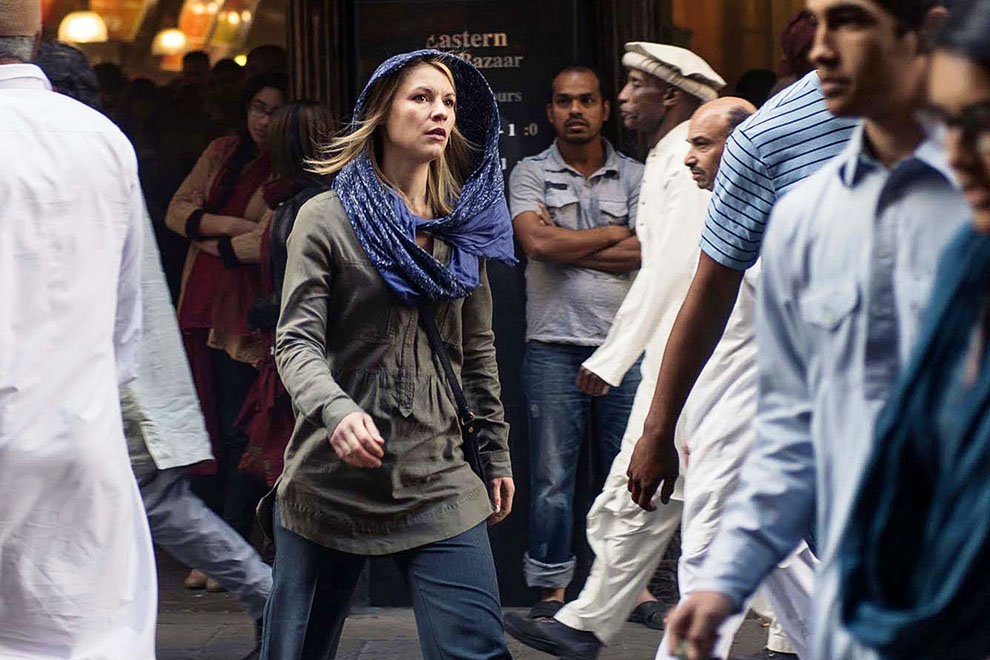

In series five, it’s over to him and Claire Danes as former CIA agent Carrie Mathison, drawn back into a dangerous mission in Lebanon in spite of her new commitment to lead a regular life as the mother of a three-year-old. Completing the trio of leads is Peter Quinn, Mathison’s ambitious colleague in an earlier series, whose ruthless streak is getting more pronounced. All three are hardbitten and stoical, yet in their different ways volatile. Australian actress Miranda Otto as Berenson’s station chief in Berlin – poised, professional but canny enough to be disruptive if the cards fall against her – is an effective addition to the chemistry.

The psychodynamics are such that you never know where any scene is going, but there is a deeply impressive consistency about the handling of the political environment of CIA field operations. The storylines repeatedly take Mathison on location to war zones in the Middle East, and although these were filmed in Germany in constructed (or deconstructed) sets, the atmosphere and social milieu of the region is evoked with thoroughness and sensitivity. •