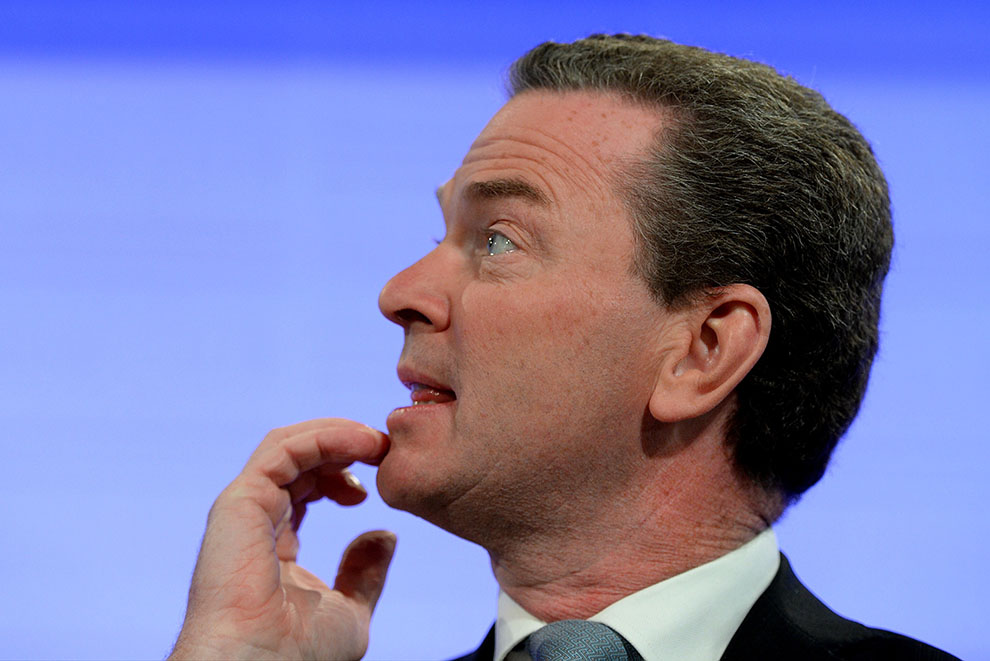

Christopher Pyne’s appointment of right-wing warrior Kevin Donnelly as one of two reviewers of the national curriculum was greeted with howls of outrage. The just-released Donnelly–Wiltshire report, by contrast, has provoked little more than quibbles and grumbles, many of a practical rather than an ideological kind. Troops readied for a resumption of the culture wars have been stood down. An air of puzzlement prevails.

A report from this minister, in this government, that tries to accommodate a range of views? That endorses Labor’s idea of a single national curriculum? Perhaps it is just that the critics were so fixed on Pyne’s sheer gall in appointing Donnelly that they failed to notice that he also appointed a minder, that wily operator of the machinery of influence, Professor Kenneth Wiltshire? Or perhaps Pyne has at last grasped the difference between opposition and government, and decided to box smart? On this interpretation, Donnelly and Wiltshire are sappers, preparing bridgework for a long assault on that bastion of the “cultural left,” the school system. The most satisfying construction is that Pyne’s antics on Gonski plus a mounting electoral backlash against his higher education “reforms” caused the PM’s office to put Pyne on notice and his reviewers on a very short lead.

Whatever the explanation, the final report of the Review of the Australian Curriculum is certainly not as bad as many expected, and is in some respects useful.

The reviewers were asked to examine the curriculum’s “robustness, independence and balance,” with the apparent implication that it was unbalanced, soft, and a creature of special interests. Its three “cross-curriculum priorities” – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander history and culture, Asia and Australia’s engagement with Asia, and sustainability – seemed especially vulnerable to attack from this angle. Few observers would have been surprised to see it replaced by the Coalition’s preferred trinity, Judeo-Christian values, British heritage, and our free-enterprise economic system. That, after all, seemed to be what John Howard himself had urged back in the opposition years.

On these dire expectations the reviewers declined to deliver. They did find the national curriculum to be “monolithic, inflexible and unwieldy,” and pooh-poohed its claims to be “world class,” but they also accepted that it was basically a good idea. They conceded that the curriculum is in fact “robust” in some if not all learning areas; that threats to its “independence” came less from ideology or interest groups than from the demands of states and school systems; and that while more needed to be said about our Judeo-Christian heritage and so forth, the three priorities installed under Labor should be relocated rather than abandoned. The review did propose changes in the Labor-installed ACARA (the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority) but not, as some expected, its abolition.

Many of the review’s other recommendations address non-incendiary matters such as the overloading of the primary years, the need to adapt the curriculum for students with disabilities, and the need for more parent-friendly development processes and documentation.

For several decades from the 1960s debate over schooling in general and curriculum in particular was split along ideological lines on just about every conceivable issue: how to teach reading (phonics versus whole-word), teacher-centred versus student-centred pedagogy, fields of study versus the great disciplines, content versus process, direct instruction versus constructivism, reading the classics versus understanding genres, rigour versus inclusiveness, knowledge versus learning to learn, excellence versus equality, reward for merit versus success for all, and, of course, choice versus the common school.

Polarisation often prevented participants from acknowledging that many of these oppositions are little more than coded rallying cries in the great struggle of us against them. Donnelly, like a number of his ideological companions, is has moved from one side of these false dichotomies to the other, and perhaps in consequence has been a particularly divisive belligerent right up to his appointment by Pyne in January of this year. Until just a few months ago he cast himself as the scourge of the “cultural left,” an entity which never was as monocular, monolithic or influential in reality as in his imagination, and which has not existed at all for the past decade at least. Ironically enough, several of those previously tarred by the “cultural left” brush (and notably the late Jean Blackburn) are relied on by the review.

Thanks particularly to the “teaching effectiveness” movement, the curriculum debate has moved on from grand abstractions to questions of method – questions about how to boost outcomes in the fundamentals of literacy, numeracy and science. The key to boosting “performance,” in this view, is the “quality of teaching,” and better teaching can be achieved through systematic whole-school improvement. The relatively low ideological temperature of the Donnelly–Wiltshire report is an artefact of this consensus. Indeed, Pyne’s “four pillars” (teacher quality, school autonomy, engagement with parents, and stronger curriculum) are an attempt to capture it.

Whether that consensus can succeed even in its own limited terms is another question. The chaotic, riven curriculum debates of decades following the 1960s (rehearsed in the report’s first chapter) can be understood as an effort to come to terms with a problem presented to rather than sought by the teaching profession: what is the purpose of twelve years of schooling, for all? Even harder: how is it to be done?

The reviewers acknowledge these problems. They suggest that the “missing step” in the development of the national curriculum was the failure to construct an “overarching framework,” and that this led to the curriculum’s problems of coherence and bulk. But having made those useful observations, the reviewers join the long list of pundits who have ducked, adding only the suggestion that further work is “urgent.” They also avoid most of the “how” questions, preferring to lean in the general direction of the teacher’s authority while also acknowledging that “all good teachers use a variety of pedagogical approaches.”

Conspicuously absent from this formulation and from the report as a whole is any reference to a central question for the future of teaching and learning (or what some refer to as “curriculum delivery”): what will and should be the role of the digital technologies? The teacher-quality paradigm on which the reviewers tacitly depend is undoubtedly the best option for most schools in the short-to-medium term, but beyond that? Often seen as a new dawn (to borrow Debussy’s aphorism at Wagner’s expense), the focus on the teacher and teaching will prove, in my view, to be more like a glorious sunset.

In the meantime, it is by no means clear that the undoubted potential of the effectiveness approach will be fulfilled. While a blurring of ideological boundaries in talk about curriculum does reduce one obstacle to its implementation, curriculum is only one site of the ideological conflict, and that in turn is only one of the faultlines of Australian schooling. Others include confusion over state and federal government responsibilities; chronic conflict between governments and various schooling agencies and interest groups; and, of course, the sector system and its division between fee and free.

This fractured arrangement of responsibility and authority is what has made the system incapable of lifting its performance in an increasingly international competition, the almost frantic efforts of the Rudd and Gillard governments notwithstanding. The present government has lower ambitions. Will it have more success?

On the mostly positive side of the ledger are suggestions made by the Commission of Audit about a different division of labour between levels of government. On the wholly negative side are the recent solecisms of the Review of Competition Policy. Where the Donnelly–Wiltshire review can be placed is to be determined. As the reviewers themselves note, the fate of their report depends not on their minister but on what he can get past the state and non-government systems. Suggesting, as the reviewers do, that the systems have too much say in ACARA may not be a good start. Every jurisdiction is wary of yet more change, and the NSW minister in particular is hostile to any sign of federal interference. All will want to know what the Abbott government proposes to do about money.

The Donnelly–Wiltshire report opens with the observation that “there is little as controversial in education as determining what it is that young people should be able to know, understand and be able to do following their time at school.” Their review attracted 1600 submissions. Gonski’s funding review received 5700. •