First published 27 August 2016

Play All: A Bingewatcher’s Notebook

By Clive James | Yale University Press | $35.95

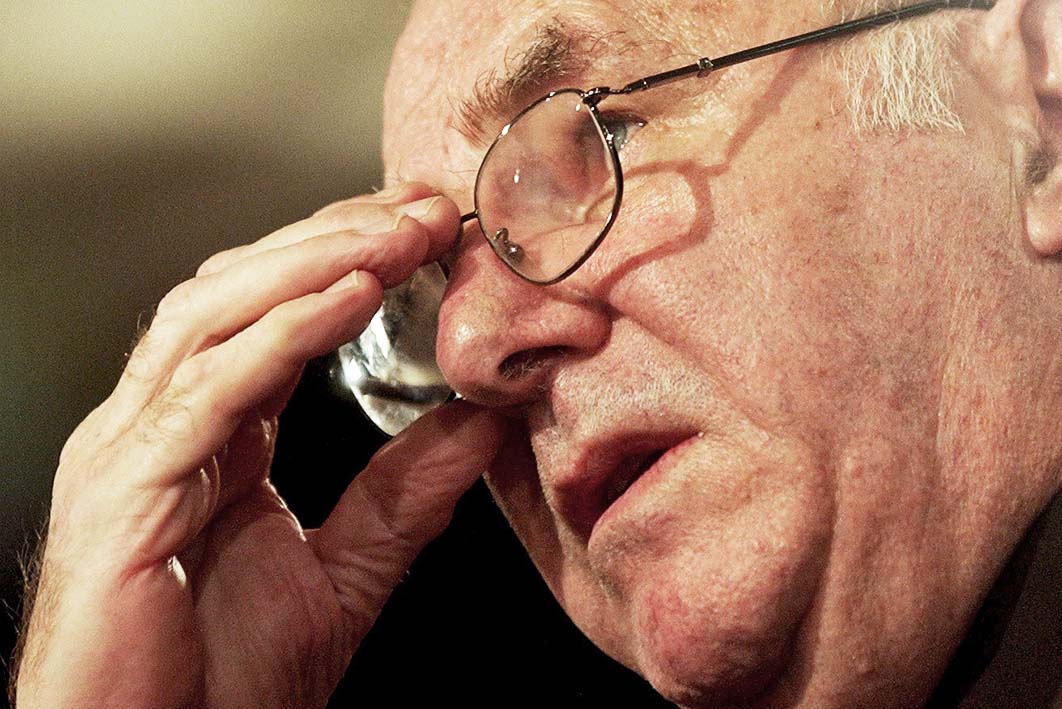

Clive James has taken to prefacing his books with an update on his circumstances. He was diagnosed with leukaemia in 2010 and told he had just a few years to live, so, determining that he might as well read – and write – till the lights went out, he moved with his books to premises in Cambridge that he refers to as “a library.” Since then, the terminal prognosis seems to have become a little hazier. A new drug has extended his lease of life and so he continues to fill his days with reading and writing, counting the bees, watching the goldfish in his daughter’s pond and walking the mile to town with “the right technique for wading through deep clay.”

Poet, philosopher and polymath, with an intellectual range that has swept through the works of Dante, Proust and Samuel Johnson, the major poems of Browning and several hundred of the best twentieth-century novels in the years since his diagnosis, Clive James is also something of a media junkie. He likes watching TV. A lot. For a couple of decades he liked being on it, until in 2000 he decided that the “Blaze of Obscurity,” as he put it, was getting to him. So he wrote a book about it, and retreated to more contemplative pursuits, though those did include regular contributions as a television critic for London’s Daily Telegraph.

His gifts as a humourist were his passport when, having managed to infiltrate the inner circle of Private Eye editor Peter Cook in the early 1960s, he began to make his mark as a journalist who could execute the equivalent of a stand-up comedy routine on the page. As a television presenter, James’s style was like that of a virtuoso bowler on the cricket field. He’d set up a statement with an opening gambit, spin the cadence through several parentheses, and deliver the shot from an angle no one else would have found. His Postcard from London opens with a dry narrative voiceover: “A long time ago some hairy character painted blue slung the carcass of a recently slain stag, grunted ‘this is the spot’ and told his wife to build a house. Before she even finished pouring the mud floor, distant relatives were already arriving and since then, no one has ever gone home again except the Roman army and the German air force.”

Clive James the stand-up comic has a way of making reappearances in the writing of Clive James the contemplative. It’s as if the very texture of the prose gives him an entry. A sentence takes a particular turn, and you can actually hear the grain of the voice as it winds around to deliver the zinger. But the relationship between these two personae is a little uneasy. In Play All, a new collection of critical essays on “box set” television series, the comedic voice is muted: always there, as if trying to resurface, but only making it in brief forays. The mood spectrum of the later James just has too much melancholy in it to allow those improvisational tours de force to take shape.

Binge-watching, as he acknowledges in the opening pages, became a way of managing what he had been told was the closing phase of a life span. There will be some who approach this book as fellow travellers in states of severe illness, needing something to do with the days and nights. And for many of us, binge-watching is now a way of life, a new form of fiction addiction that offers better-quality material than the thriller shelf in the bookstore.

The binge-watching trend is a consequence of a minor cultural renaissance in television drama production. James tracks the new canonical works of “quality TV,” a phenomenon that arose when the box became the flat screen and a high culture began to infiltrate via the box set. There’s a broad consensus that the trailblazers are Warner Bros’ The West Wing (1999–2006) and HBO’s The Sopranos (1999–2007), followed by the Hanks/Spielberg produced miniseries Band of Brothers and HBO’s Six Feet Under in 2001, then HBO’s The Wire, starting in 2002.

By 2007, when The Sopranos is over and the addicts are scanning the scene for the next fix, the options are opening up. The Scandinavians enter the arena with The Killing, Lionsgate’s Mad Men provides a bold change of genre and Breaking Bad, starting early in 2008, manages to get a following for a middle-aged hero in Y-fronts. After that, the competition for canonical status is stronger by the year. What makes the cut is a matter of Emmy Award counts and personal judgement, and James’s selection is unashamedly arbitrary.

In one sense, Play All is a misleading title. James favours the US repertoire, contributing to the presumption that quality TV wasn’t really quality TV until the Americans came up with it, regardless of such landmark British precursors as Prime Suspect, House of Cards (the BBC version), Edge of Darkness, The Singing Detective, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy and Smiley’s People. The Scandinavians get short shrift from James, and he seems to have no time for such recent British successes as Sherlock, Line of Duty, Happy Valley, The Fall, Wolf Hall or London Spy.

So this is essentially a book about American canonical television – part story of its evolution, part critical diagnosis of what makes or fails to make great television drama. James begins at the beginning of The Sopranos: a close-up of Tony Soprano’s face “creased with effort on its various levels and terraces” as he responds to a sudden and unanticipated loss. The ducks have taken off from their winter habitat in his swimming pool. James ponders on how the actor James Gandolfini, so good at fading into the background on film, occupies the television screen as “a magnetic mountain, pulling toward him all legends of haunted loneliness and seismic inner violence.”

Clive James is at his best when he’s mining for depths of field, as in this chapter on The Sopranos and, at the end of the book, on Game of Thrones, where it’s as if he’s trying to mediate between the facetious and contemplative halves of his own mind. Fascinated with kitsch as he always was (and hilariously fascinated by his own fascination with kitsch), James admits to a prejudice against swords and dragons that caused him to leave the GoT box on the table for months before mustering the determination to fight his way through the shrink wrap.

His account of the series is a narrative of his own conversion. He’s won over first by the image of a throne of a thousand swords, with its binding political symbolism, and then by the masterful economy of the script: one of the salient qualities of the long-form television drama, he says, has been to employ the utmost sophistication to face us with the primitive. Most of all, though, the addictive lure into the five-episode binge session is Peter Dinklage as the dwarf Tyrion Lannister, whose “big head is the symbol of his comprehension, and his little body the symbol of his incapacity to act upon it.”

It’s a brilliant formulation, even if it’s actually wrong. Tyrion fights his way through one of the most gruelling battle scenes in the series, and engineers a succession of shifts in the balance of power as he journeys through the seven kingdoms. James’s verbal brilliance habitually leaps ahead of his critical judgement, though not always. And when it comes to being a genius of eloquence, it takes one to know one. Tyrion’s eloquence gets him through one scrape after another, but in the trial scene where it is on full display, James is impressed with how Dinklage pays attention to “what he looks like when he listens.”

Eloquence is a fine thing, but it can run into a form of hyper-articulateness, and here James finds another fellow traveller in Aaron Sorkin. The younger Clive James is indeed a character who might have been written by Sorkin, and who better than James to provide insight into the quirky mystique of the Sorkin script? Although it’s ten years now since The West Wing was laid to rest, it remains, says James, “our first frame of reference for thinking about the presidency,” though I suspect that line was written before Trump became a serious White House prospect. Imagine Trump making a beeline for the Oval Office while being briefed by Toby Ziegler or C.J. Cregg. Even they would not have got a word in edgeways. When I rewatched The West Wing a year ago, I was bothered by how the characters are all at least 20 per cent Groucho Marx and talk alike. Or, as James observes more knowledgeably, Sorkin transplanted the rapid-fire dialogue of classic Hollywood prewar comedy and gave it a new lease of life for television cameras that were good at moving fast down corridors.

As a book, Play All has some problems. James seems to lose direction and momentum in the middle, steering all over the road as he tries to cross reference one series with another, making comparisons in the rather random way you do in discussion with your fellow couch potatoes between episodes. Why, when he finds a series that isn’t worth watching, does he think it’s a good idea to spend three pages telling us about it? Of course, James can always find a few critical points to make, to diagnose, for example, where the configuration of elements in Treme doesn’t work with the dynamism that made The Wire a succès d’estime among such connoisseurs as himself and Barack Obama. But this isn’t really critical analysis, it’s just a way of rabbiting on to fill up the chapter, and while Clive James’s rabbit may be better than most people’s best paragraphs, readers bore easily these days, more easily than television viewers, and there’s no end to the good work that can be done with a delete key.

His descriptions are brilliant but his judgement is erratic, and he’s never at his best when he indulges it, especially when it comes to the appraisal of female cast members. James was always captive to a 1960s culture of the male gaze, and that hasn’t changed. He’s seduced by the “outstandingly disarming” and “radiantly intelligent” Birgitte Nyborg in Borgen, but not by Sarah Lund – “a thin bundle of neuroses plunged into the gloom of a bad sweater” – in The Killing. He fancies Cersei Lannister in Game of Thrones for combining “shapely grace with limitless evil” but not Daenerys Stormborn, who is “not much more than the average princess next door.” It’s enough to make Don Draper blush and Groucho Marx head for the nearest punchline. The convention for this kind of erotics-driven judgement is to turn it into a kind of self-abnegating gallantry: “Personally I can’t get enough of being told what to do by powerful women, but I’m half dead.”

Personally, I don’t care too much about these lapses in protocol. Television is a culturally permissive medium and must remain so if it is to survive. James’s recognition of this is one of his great gifts as a TV critic. He winds up his discussion of GoT by forgiving it for being a crowd-pleaser, dragons and all. “To despise that, you have to imagine you aren’t part of the crowd. But you are.” It’s the lesson the twentieth century taught all intellectuals, he says, and in this new century, they must go on being taught. And television remains the medium best placed to teach it. •