Part of our collection of articles on Australian history’s missing women, in collaboration with the Australian Dictionary of Biography

Among her many achievements on ice, Sadie Cambridge won the pairs event of the Open Professional Championship of Great Britain in its inaugural year at Oxford in 1932, the first of seven straight titles with her husband, Albert Enders. She went on to become a coaching pioneer in singles, ice dance and pairs, and her students’ many successes included Olympic and World Championship bronze medals for Canada in 1948. She and her husband were the first Australians to be inducted into the Skate Canada Hall of Fame.

Born Sarah Elizabeth MacCambridge on 25 March 1899 at Alexandria in Sydney, Sadie was the only child of James MacCambridge, a railway labourer from Glasgow, Scotland, and Elizabeth nee Lyons of Sydney. She attended Fort Street Girls’ High School, and at fifteen represented her state in the women’s swimming championships of Australia under the auspices of the NSW Ladies’ Swimming Association. But her real love was ice skating. Even when she practised her edges as a schoolgirl, and later aspired to a spiral or two, people used to remark on what a fearless skater she was.

Her skating instructor at Sydney Glaciarium, Melbourne-born Albert Enders, recognised a potential champion in Cambridge after one season. By the time they were in their early twenties he and Sadie were performing skating exhibitions in Sydney and Melbourne, showcasing adagio neck spins, death spirals and other advanced skating skills of the time.

Enders suggested she should take her talents abroad, and the pair left for England under engagement to the newly opened London Ice Club. One successful season later, they were a couple. In 1929, Cambridge achieved the National Skating Association Gold Medal skating standard; not yet thirty, she was among the elite few to have reached Britain’s highest level of skating.

Based in London for many years, Cambridge regularly returned home to teach and perform with Enders, and was often called on by the local press for skating fashion tips. The pair popularised the side-by-side Jackson Haines spin in the twenties, and followed the development of ice ballet and ice dancing in Europe with enthusiasm.

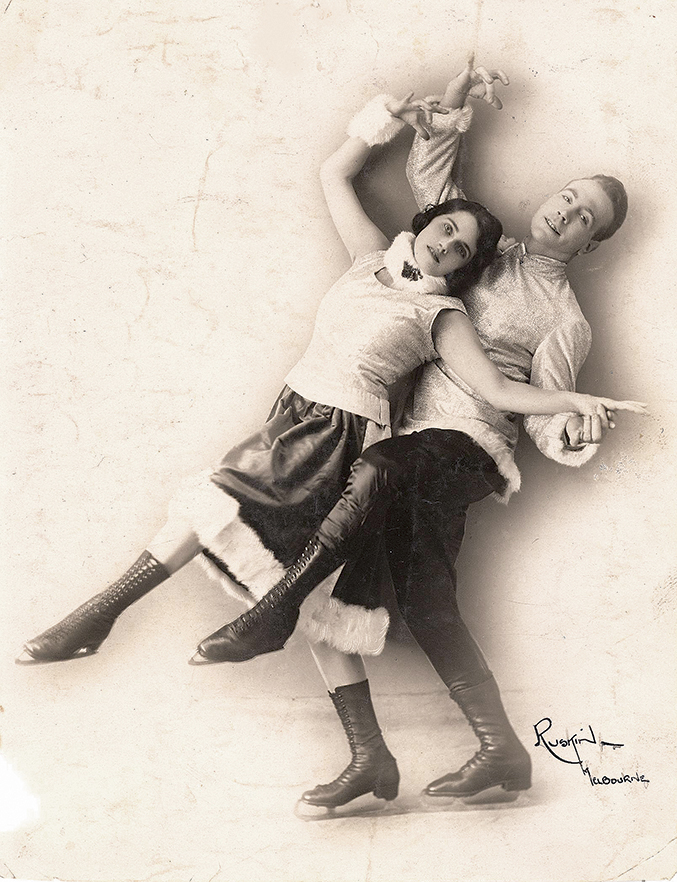

Sadie Cambridge and Albert Enders photographed in Melbourne, c. 1920s. Skate Canada Archives

Skating was very fashionable among the London aristocracy. Cambridge’s students included the glamorous heiress Edwina Ashley, who would marry Louis Mountbatten; and historian Frederick Smith and his sister Eleanor, many of whose romance novels were adapted for the screen. In 1930, Cambridge performed at the St Regis Hotel in New York, where renowned skating coach Gustave Lussi directed and choreographed shows.

In the seven years after their wedding in London in June 1931, Cambridge and Enders won the Open Professional Championship of Great Britain no fewer than seven times, and were declared world professional champions in British pair skating. They taught and produced ice ballets at the Queen’s Arena before returning briefly to Sydney, where Cambridge’s mother had fallen ill. Accompanied by their young pupil, Daphne Walker, they gave a gala performance at Sydney Glaciarium that was filmed by Fox Movietone News.

In 1936, they again performed at the famed Palais de Sport in Paris and played ice hockey before 15,000 people. Later, they invited ice hockey player and speed skater Ken Kennedy, Australia’s first winter Olympian, to join their travelling troupe. On the move again, they spent time in Johannesburg, working from early morning until after midnight, managing, teaching and performing, until they turned Empire Exhibition ice rink from “a hopeless proposition” — as Sadie later said — into “an unqualified success both financially and socially.”

Cambridge’s students at the Queen’s Arena, London, included Pamela Davis MBE and Mollie Phillips, the first woman to carry the flag and lead out her national team at an Olympic Games. Both later became International Skating Union judges, and Phillips was the first woman to referee a World Championship.

In 1938, Cambridge and Enders performed in Tom Arnold’s “Switzerland Musical Extravaganza on Ice” at the Liverpool Empire. The following year they returned to Melbourne with Walker, who was by then a gold medallist of Great Britain and fourth-placed in the British open championship. Walker went on to become the 1939 World women’s figure-skating bronze medallist, the 1947 silver medallist, and the 1939 and 1947 European bronze medallist.

When Cambridge and Enders finally settled in Canada in 1940, they chose the Winter Club, the most prestigious private sports club in the city, as their base. Their Montreal students included Dwight and Libby Parkinson, who both enjoyed distinguished careers as amateur skaters and judges, and Norman Gregory, a key developer of figure skating in Canada.

Over the years that followed, Cambridge’s students won most of the pairs and fours in Western Canadian Championships, as well as many other dance championships. Suzanne Morrow and Wallace Diestelmeyer developed the current one-handed version of the death spiral in the 1940s, and went on to win Canada’s first-ever Winter Olympic medal in the pairs event — a bronze, at St Moritz in 1948. Her pupils Frances Dafoe and Norris Bowden later won the silver medal at the Cortina d’Ampezzo Olympics in Italy. All four students produced World Championship titles in pairs skating, some competed in the singles events at the Olympics, and some served as figure-skating judges.

Among Cambridge’s pupils were the first pair skaters to do the twist lift, throw jump, “leap of faith” and overhead lasso. Some of the rules in pairs skating changed because of Cambridge’s work with such skaters as Dafoe and Bowden, now an honoured member of Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame and the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame.

Cambridge and her husband were good at the business side of the sport and worked hard. They travelled with ice shows in Australia, Europe, Britain and South Africa, and presented shows all over British Columbia between 1947 and 1960. A former student once remarked that most people involved in skating at that time would agree Enders and Cambridge really brought skating to Western Canada.

Sadie Cambridge died peacefully at the age of sixty-nine in Vancouver, Canada, on 1 September 1968, survived by her husband. The couple had no children. A coaching pioneer in singles, ice dance, and particularly pairs, Cambridge was a fearless competitor who saw her sport as an art akin to ballet, to be perfected over a lifetime. She show-skated into her sixties, and trained some of the top young skaters of her time in Australia, England and Canada. •

Further reading

Historical Dictionary of Figure Skating, by James R. Hines, Scarecrow Press, 2011