Albania is one of those Balkan countries too easily misunderstood, overlooked or stereotyped, with a history most conveniently described as “complicated.” One person who has helped the wider world get a better sense of its recent past is Albanian-born-and-raised writer Leah Ypi, a professor of political theory based at the prestigious London School of Economics. While she has often placed Albania at the centre of her political theorising, Ypi spectacularly broke through to a mainstream international audience in 2021 with her memoir Free: Coming of Age at the End of History.

Free is charmingly told from the perspective of a child reared by society to venerate communism, Stalin and most of all “Uncle Enver” Hoxha, Albania’s communist dictator. Hoxha’s death in 1985 marked the beginning of the end of communist rule, and when it finally collapsed in 1990–91 teenaged Ypi was forced to reckon with shattered illusions, family truths and the onset of capitalism, all alongside the usual adolescent torments. Until then her family — and most of all, her beloved French-speaking paternal grandmother Leman, whom she calls Nini — had protected her from what was really going on.

Ypi’s award-winning memoir has since been translated into more than thirty languages and a friend who not long ago visited Albania’s capital Tirana reports that Free is prominently displayed all over town, clearly pitched at tourists as the book to help them comprehend the country they are visiting.

Inside Albania and across the Albanian diaspora, Ypi’s reputation as an authority on the country she left as a young woman is — not surprisingly — mixed. To at least one critic, she’s an apologist for communism and a denigrator of capitalism who has turned her own critique into a commodity. Here I’m paraphrasing an online response to a long-lost photograph not of Ypi, but of her grandparents Leman and Asllan. The photo came to her attention after a stranger shared it on social media.

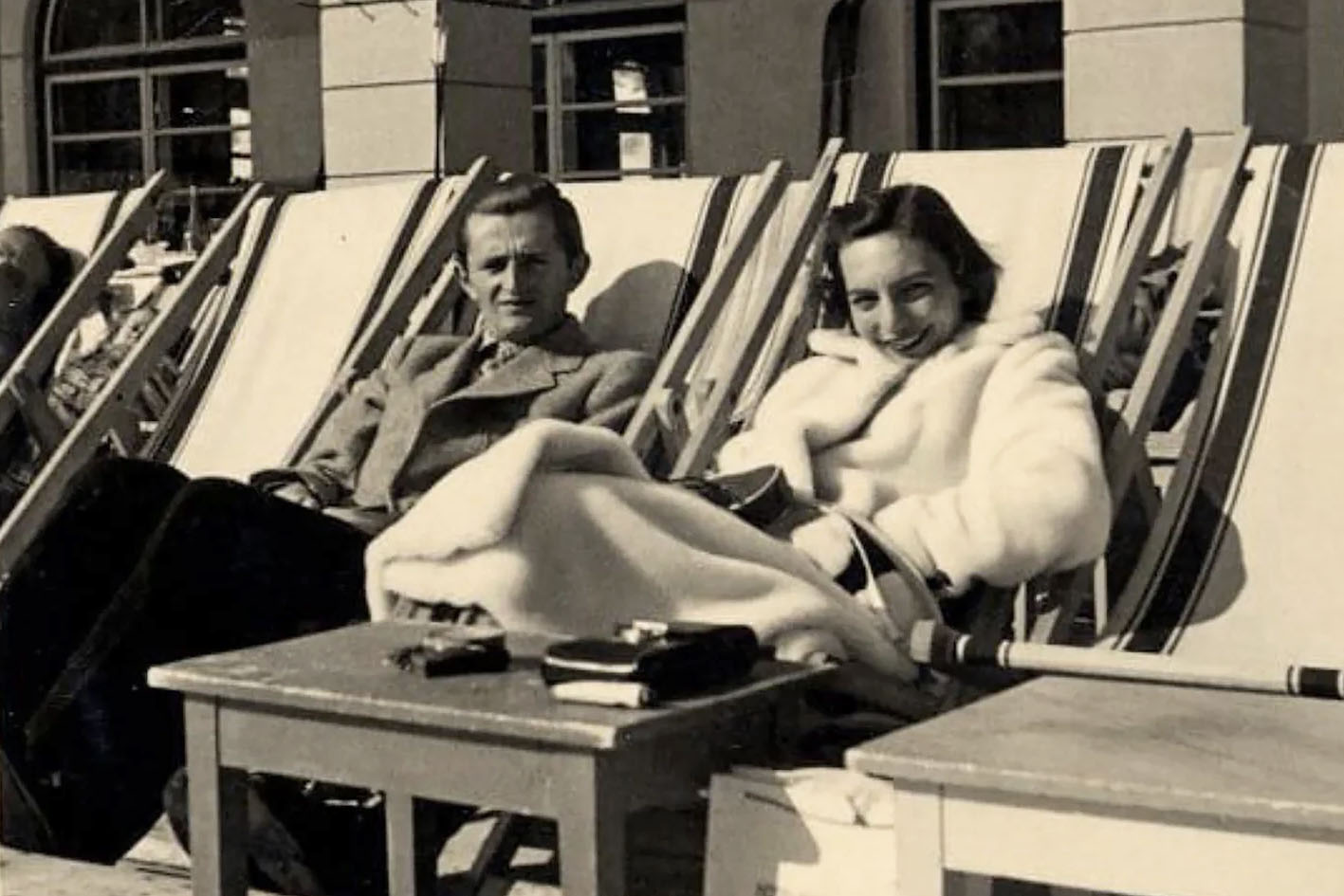

Ypi had never seen the photo before, but from her grandmother’s stories she knew it showed the couple on their honeymoon in Cortina d’Ampezzo in the Italian Alps, where her grandmother “felt the happiest woman alive.” The year was 1941 and war was engulfing Europe. Yet this “young, glamorous couple,” the woman clad in a “long white fur coat,” are “relaxing on sun lounges in front of a luxury hotel.” A pair of skis is propped behind them.

As she tells us in the prologue of her ambitious new book Indignity: A Life Reimagined, Ypi was soon absorbed by the question of “what it meant to feel the happiest person alive in the winter of 1941.” Further unsettled by another commentator’s suggestion that Leman was “a communist spy” and “before that, a fascist collaborator,” Ypi set out to defend her late grandmother’s dignity and to find out more. Well aware that these are possibly irreconcilable motivations, Ypi presents her quest in two different registers.

In the first person, in a recognisable present-day, Ypi visits archives in Albania and Greece and ponders historical silences and archival gatekeepers. Some of her reflections are banal — for instance, as historians tell her, the “best kept secret about archives” is that “it’s more about what you don’t find rather than what you do.” Elsewhere, her frustrations are vividly presented: “I am lost in my grandmother’s files as if in a labyrinth of sophisms.”

Selected historical documents are interspersed throughout, inviting contemplation of which histories can and cannot be told through archival traces. A historical timeline commences with the Ottoman colonisation of the Balkan peninsula, which began in Albania in 1468, swiftly covers the pertinent Ottoman-related events of the nineteenth century, and devotes most attention to the twentieth century up to 1946 and the beginning of communism in Albania. The entangled histories of Turkey, Greece and Albania are foregrounded, as is Albania’s second world war, when it fell under fascist then Nazi control.

As the subtitle suggests, however, most of Indignity unfolds like a novel, with Ypi “reimagining” her grandmother’s life from her childhood in the Greek city of Salonica (now Thessaloniki), where she lived with her extended family in privileged exile. In 1936, with war threatening, Leman — the Albanian who had never been to Albania — moved there just after her eighteenth birthday. While she could easily have followed school friends to France, Italy or Austria, in the “disjuncture between what the country was called by foreigners (Albania) and how its own people referred to it (Shqipëria),” she “hoped to find the truth about herself.”

In a queue, Leman meets earnest idealist Asllan Ypi, a cousin of her best friend Cocotte, who is keen to fight fascism and distinguish himself from his hard-headed politician father, Xhafer Ypi. From here, the narrative accelerates, the couple’s lives entangled with the march of history. On Friday nights at the Café Kursal, they drink and gossip with the city’s intelligentsia, among them Enver Hoxha, an acquaintance of Asllan’s from their student days in Paris at the Lycée. Hoxha smells of onion and lavender and pours scorn on Asllan’s faith in democratic elections.

Leman and Asllan attend the bizarre wedding of Albania’s self-appointed monarch King Zog and the much younger Geraldine, a “destitute Catholic Hungarian-American countess.” Here, Ypi the first-person narrator interrupts with family lore. At the wedding — in the midst of discussing “the King’s relations with Italy and Hitler’s annexation of Austria and whether it would change Europe” and Asllan asking Leman whether she’d come across “an interesting book called The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money by John Maynard Keynes” (she hadn’t) — her grandmother proposed to her grandfather.

The honeymoon glimpsed in the photograph comes not long after Mussolini’s invasion of Albania and the violent death of Asllan’s father. Jolted by the proximity of these events to their marriage, Ypi is struck by the “apprehension on their faces” and how “Asllan looked especially sad.” She wonders who is behind the camera. Perhaps it was the French-speaking Englishman Vandeleur Robinson, who next travelled to Albania to “take part in a secret operation to support Balkan antifascist resistance.”

After an “excruciating” thirty-hour labour, as the Nazis occupation of Albania begins, Leman gives birth to her son Xhafer, or Zafo for short, who is destined to be Lea Ypi’s father. For a while “the alternative time zone of motherhood” eclipses the war outside. But when Hoxha’s Albanian Communist Party breaks away from the rest of the Albanian resistance movement and assumes power, Asllan is arrested, charged with espionage, and sentenced to twenty years in prison with hard labour.

With Indignity, Ypi once again succeeds in making Albania palpable, this time from the perspective of a fallen elite, among them her paternal grandparents. Whether or not her grandmother felt the “happiest person alive” on their honeymoon is a question she inevitably cannot answer. Once the honeymoon passes, the “life re-imagined” begins to run out of steam, despite the tragic events that unfold. The grandmother to whom she was so close while she was alive is sometimes elusive and inert on the page, despite Ypi’s admirable and rather dogged attempt to access her interiority and understand her motivations.

One of the most powerful scenes in the book is Ypi’s “reimagining” of the arrival of her family doctor Elias Levy, fatally ill, from Salonica, where he had been detained for despatching to a Nazi concentration camp. Seeking out the Jewish cemetery in present-day Thessaloniki, Ypi is guided by Dimitrios, who turns out to be Albanian, real name Denis. He reflects on the fact that “Albania was the only European country with more Jews at the end of the second world war than it had before.” When Ypi the scholar suggests it was because Albanians were mostly illiterate and did not read antisemitic literature, Denis counters with another explanation: “the old tradition of besa, the oath of hospitality.” When they stop to read the memorial plaques, their conversation tapers to silence.

As they part, Denis, undertaking a history PhD, gives Ypi some advice about the archives: don’t waste time asking about her mother specifically, instead ask about the men in her family. “I gave up researching women. Women and archives. Good luck with that. You’re better off writing a novel.”

Indignity, though, is not a novel, even when it presents as an approximation of one. It comes most alive when Ypi is writing as herself, when she opens out to contemplate what we owe the dead, and to our own shifting investments in the past. In a passage that recalls the warmth and intimacy of Free, Ypi recounts the time when her grandmother, inspired by an episode of the American soap opera The Bold and The Beautiful, asked Ypi to speak at her funeral. When Leman died in 2006, Ypi went through the grief-struck motions as requested. Twenty years later, she writes, “I am still trying to correct my mistakes, to find the right words, to mark her passing in the right way.” •

Indignity: A Life Reimagined

By Lea Ypi | Allen Lane | $36.99 | 368 pages